Architects in Agriculture

Corinna Anderson on Cedric Price’s farm work

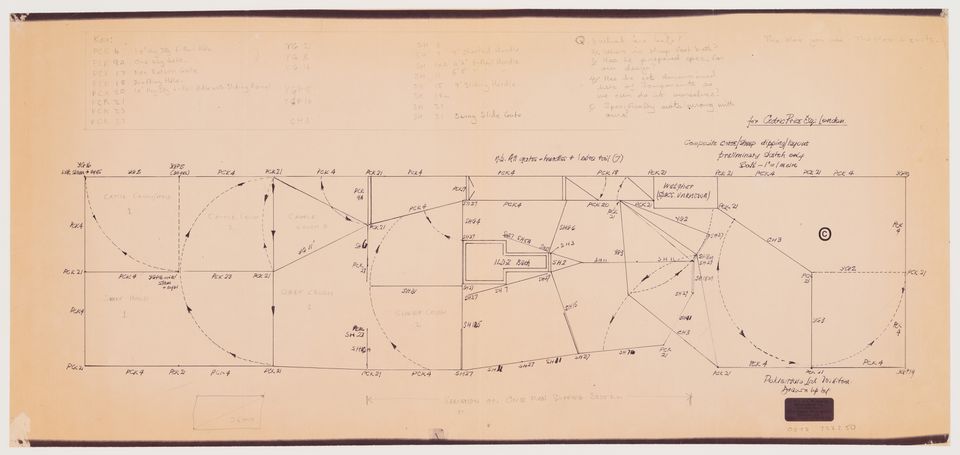

In March 1977, architect Mark Palmer of Cedric Price Architects drafted a list of questions in response to a new project brief. These included, “When and who does shearing?” “Do you ever shear and then dip?” and “Could the sheep use the cattle weighing facilities?” Alistair McAlpine—Conservative Party fundraiser, close friend of Margaret Thatcher, and heir to the McAlpine construction fortune—had set Price’s team to work outfitting his Hampshire home, West Green House, as a working cattle and sheep farm. It was to McAlpine that Palmer directed his animal husbandry questions, in a good-faith effort to figure out the basic order of operations. The optimal flow of cattle and sheep, and relationships between users of all species, would be addressed as matters of design.

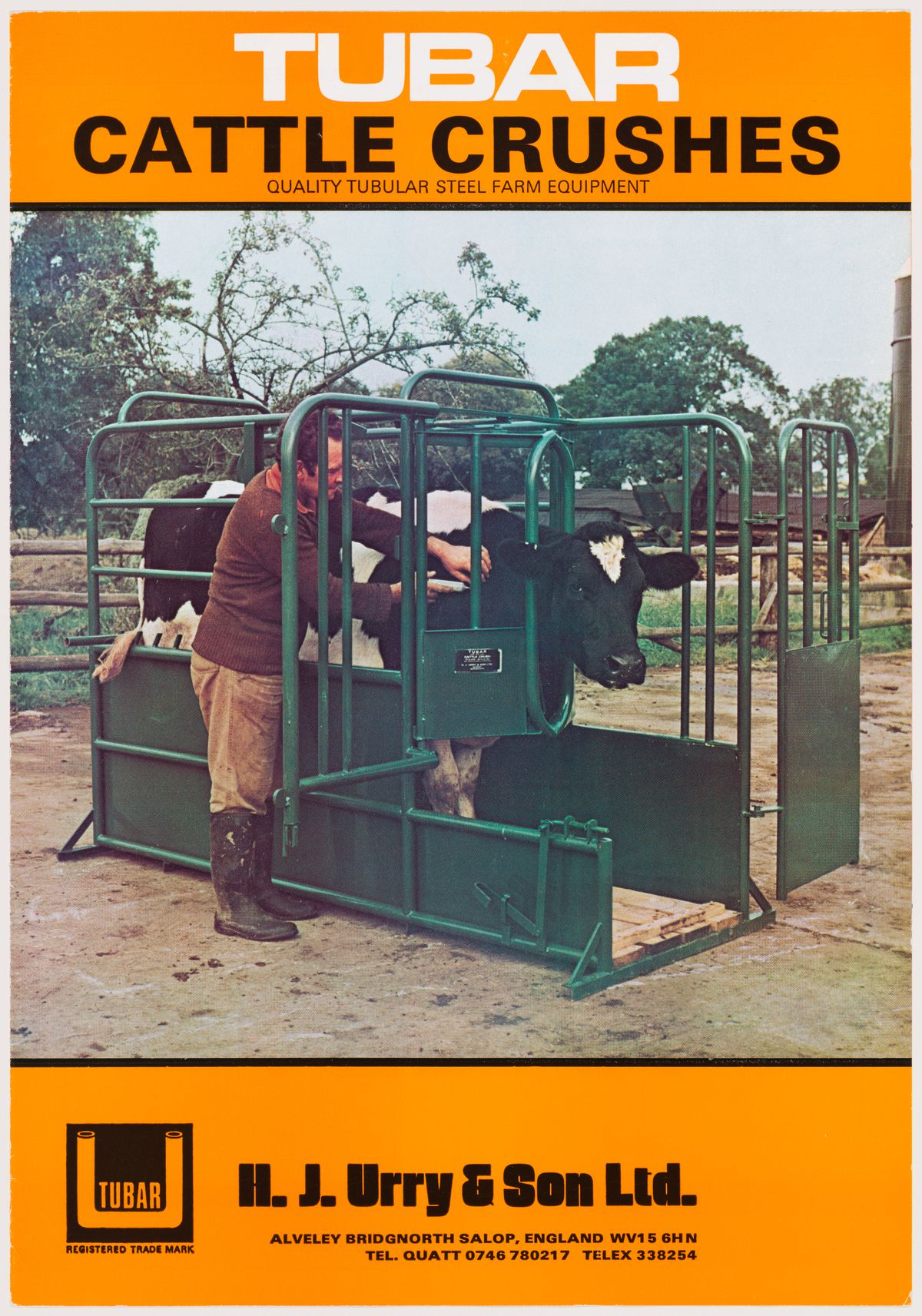

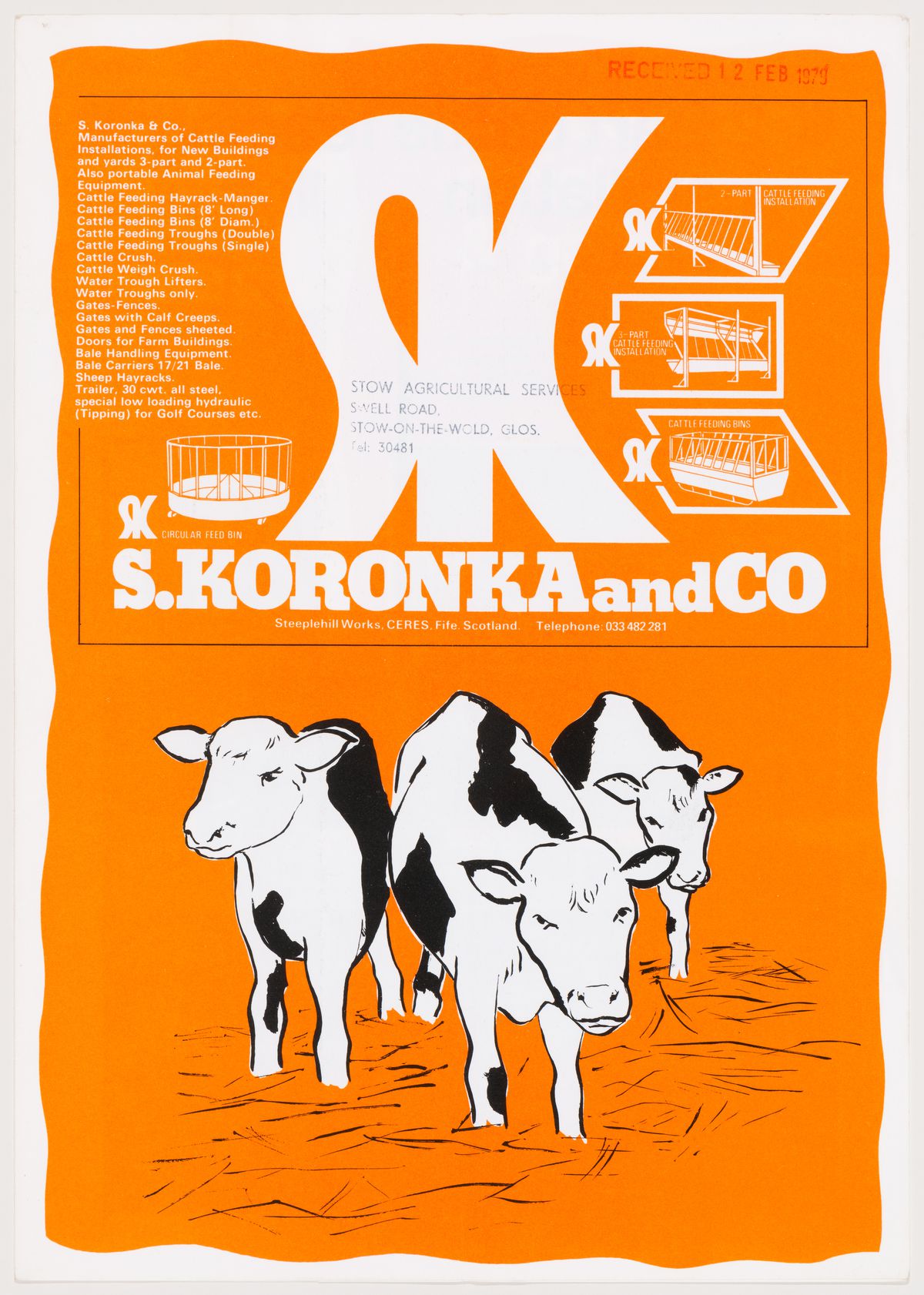

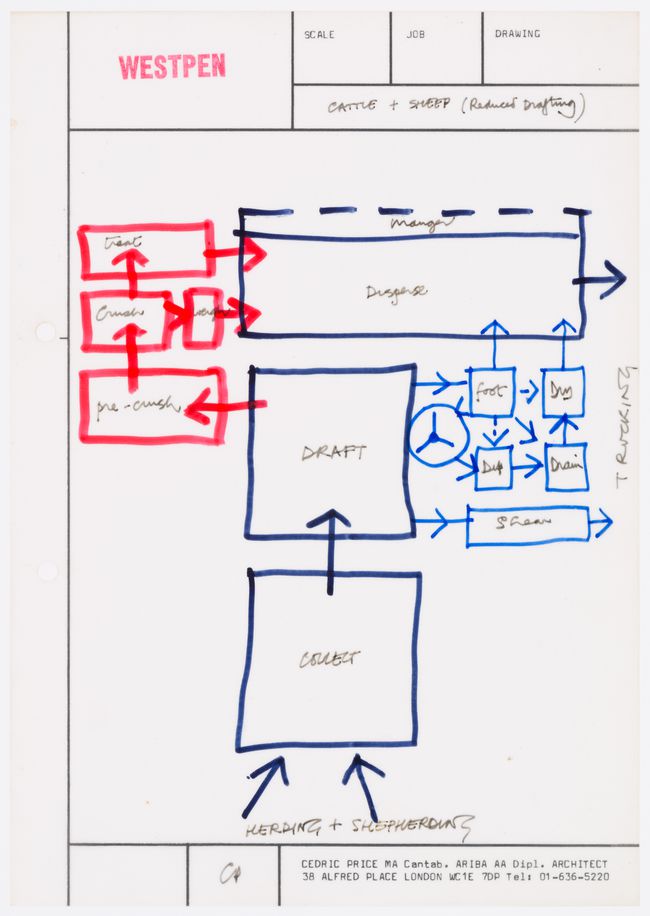

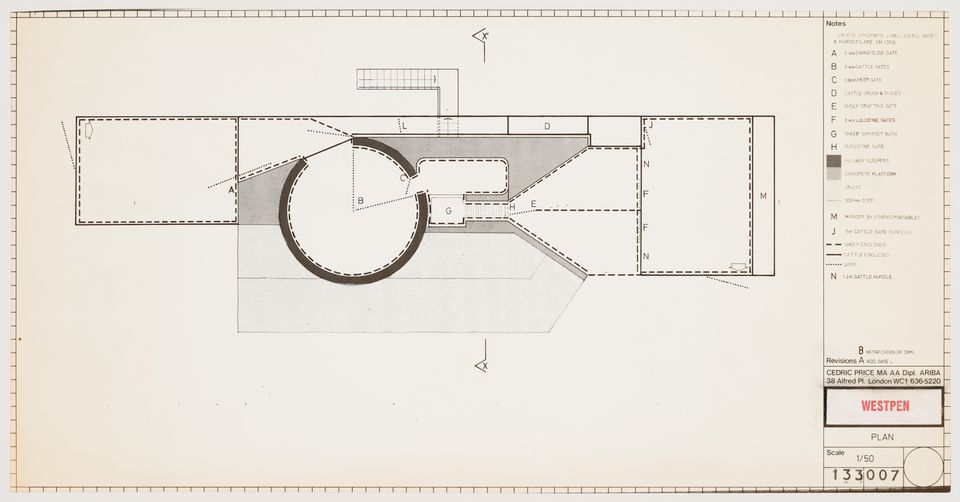

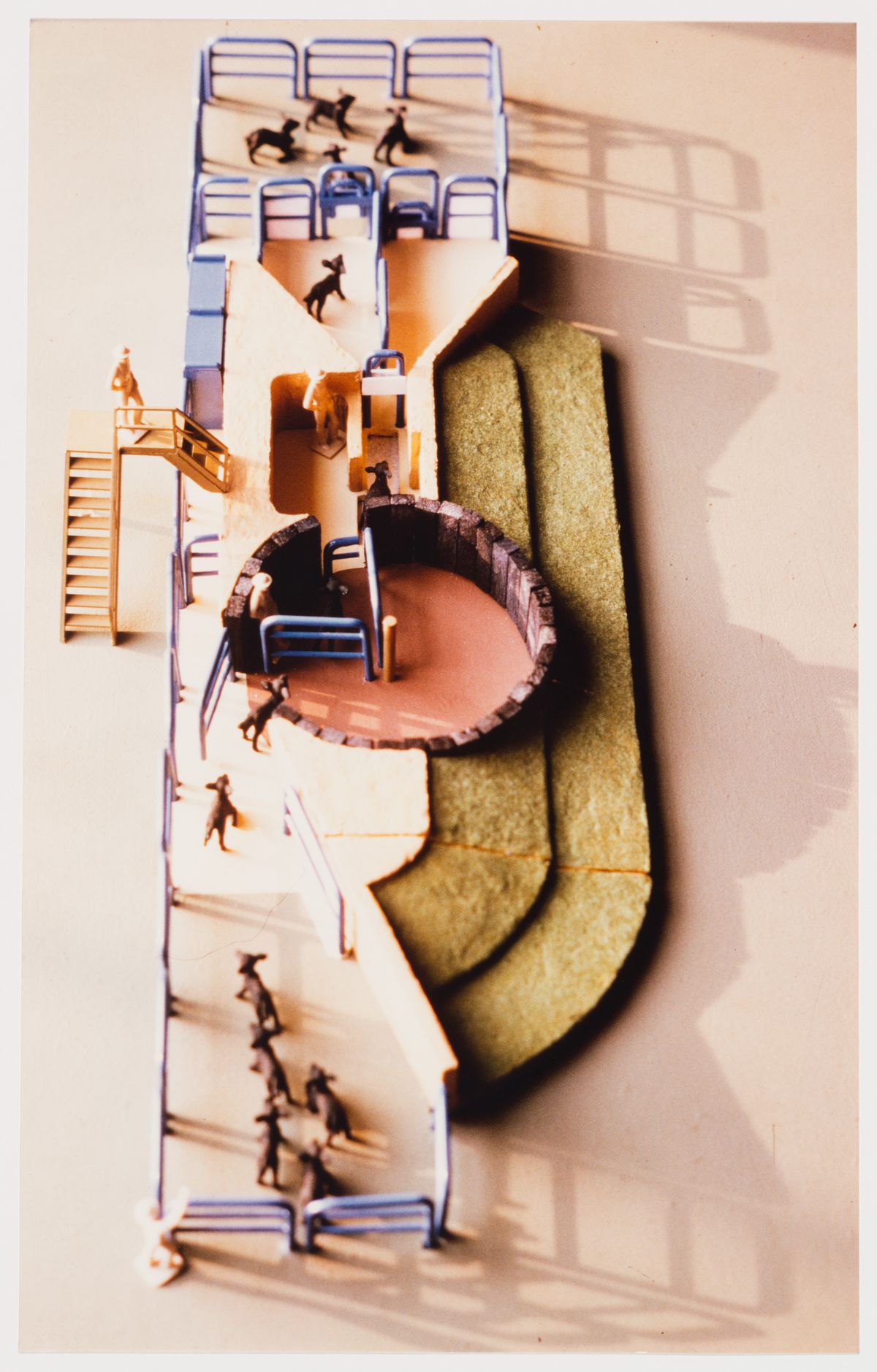

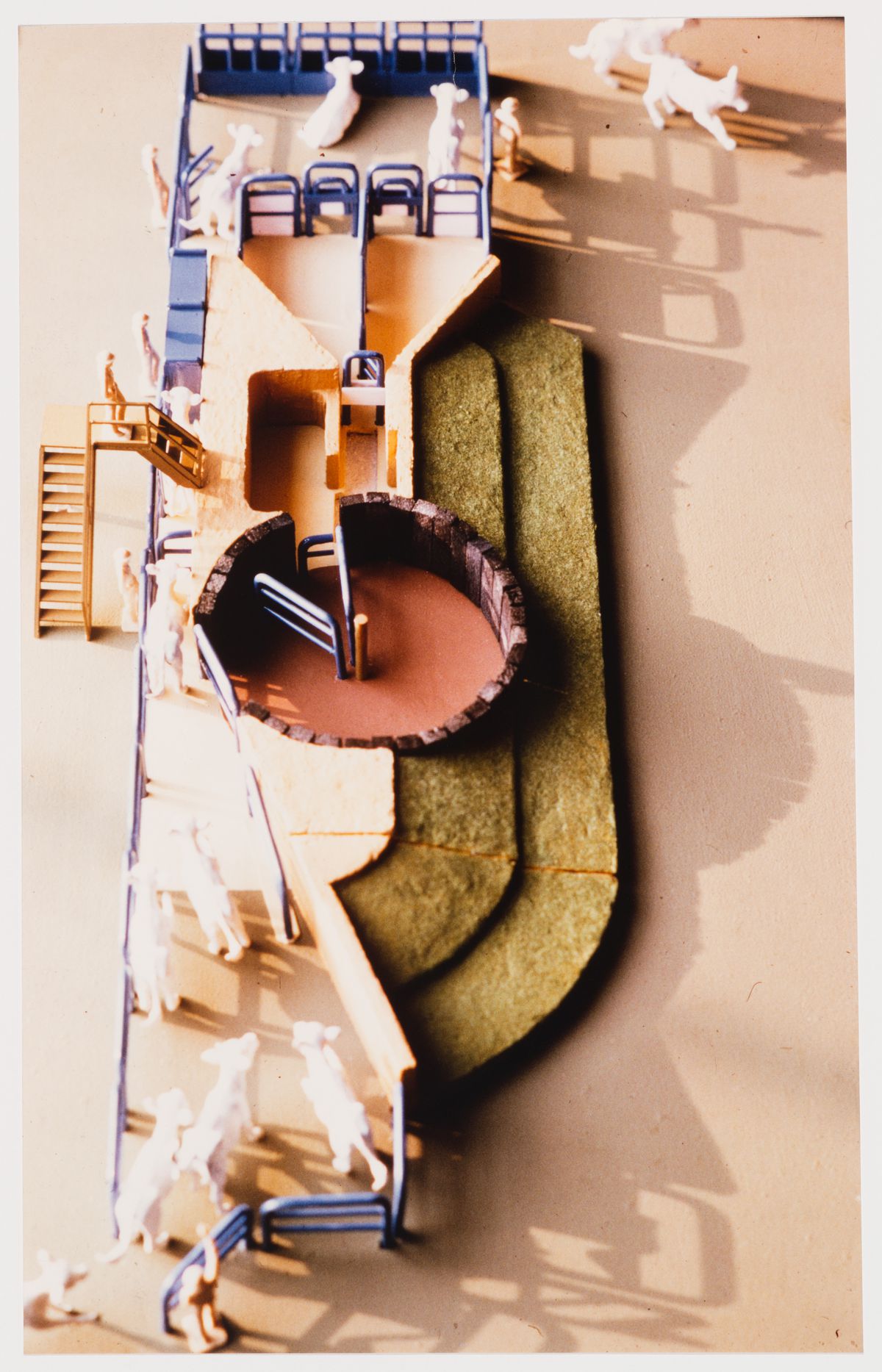

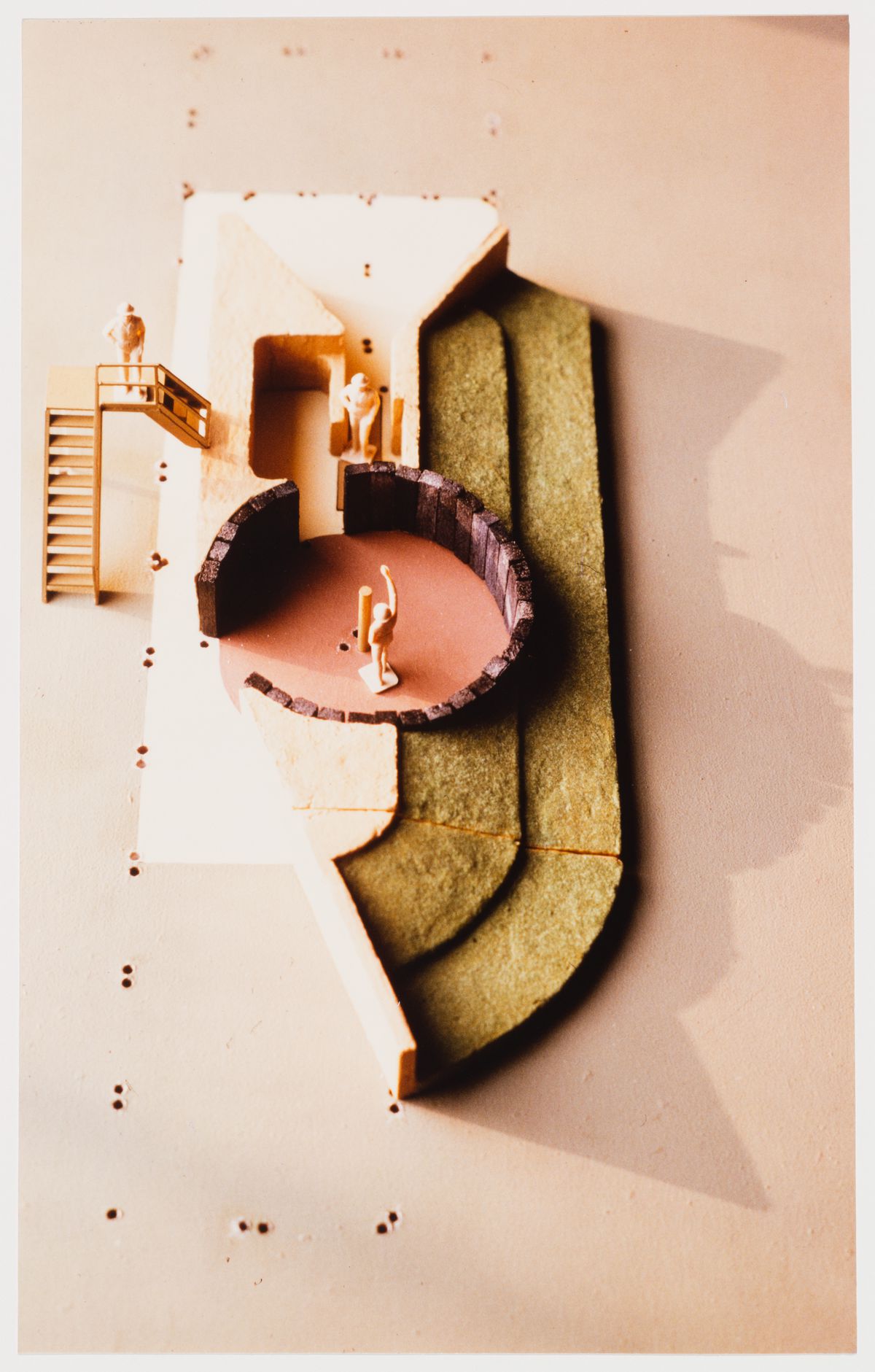

This livestock handling area, an element Price named “Westpen,” was a rarity—an agricultural brief for an architectural firm. The larger project—a whole “Westgreen Amalgam” of landscape features—would follow roughly in the tradition of the English country estate, comprising several aviaries, a pond, drawbridge, and maze. Westpen was meant to provide a cattle crush and sheep-dipping area for a herd of white English cattle and a flock of black St Kilda sheep. The project was never realized, yet in the end Price had produced a multitude of conceptual and technical drawings and a brilliantly-painted model, complete with removable parts and plastic “critturs” to demonstrate usage. In his development of the project, he went about designing for farm stock the way he usually did for people—looking first to the range of products on offer.

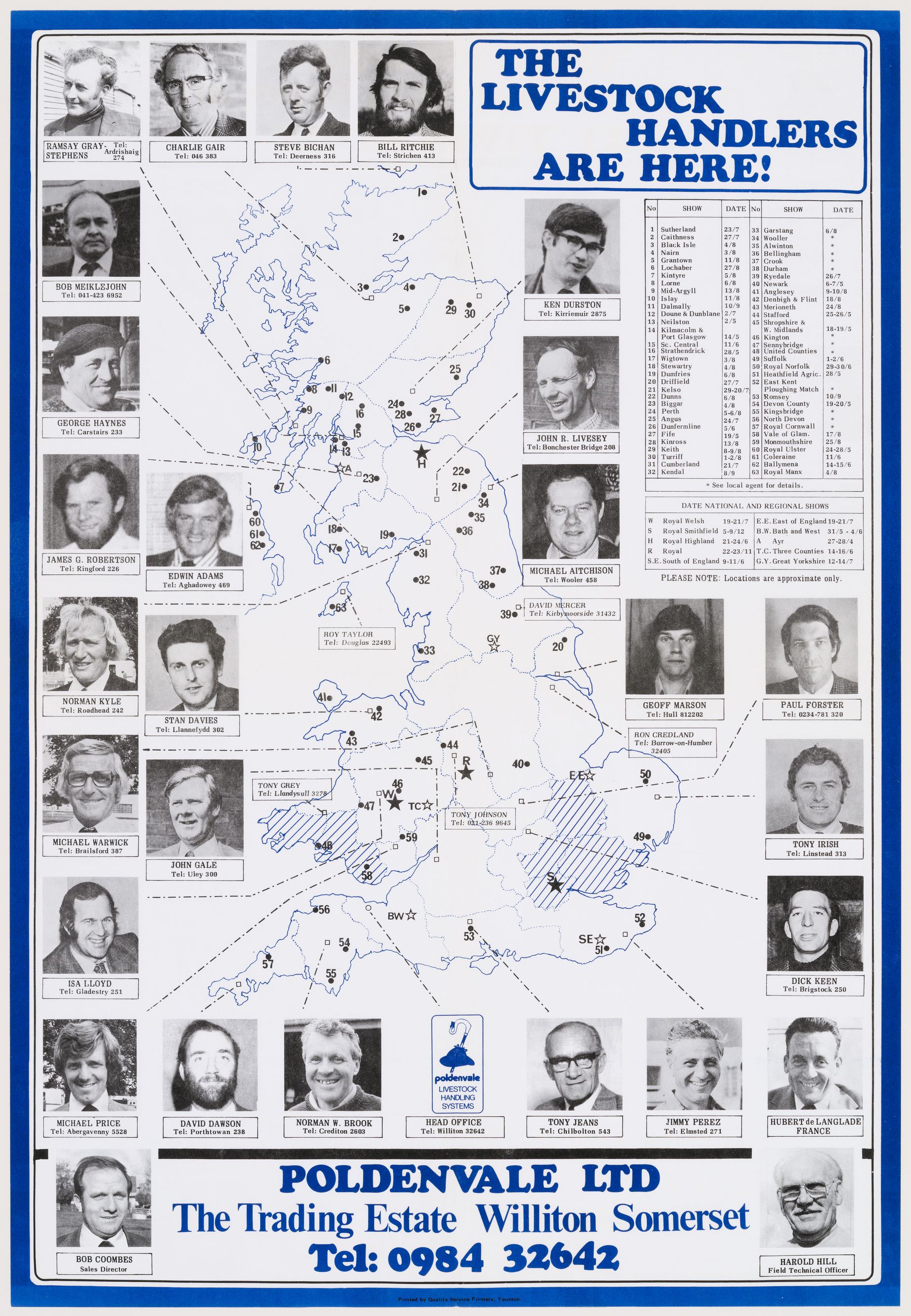

This range was immense. The agricultural equipment ecosystem, quite invisible to the average architect, included a host of small businesses and larger conglomerates, many family-owned and -operated, stretching the length and breadth of Great Britain. Price’s access to this world came via the Farm Buildings Information Centre (FBIC), a non-profit organization headquartered at the National Agricultural Centre at Stoneleigh, in Warwickshire.1 Through the directory they produced, Price’s office was able to find a few manufacturers who might help them with the task of sourcing sheep and cattle equipment. Mark Palmer hit several dead ends before coming upon a Mr. C. S. J. Sparkes of Poldenvale, Ltd. In a three-page letter dated 14 September 1977, Sparkes explained the basic principles of livestock handling to the London architects. They had drawn up diagrams of the flow of animals through the enclosure, trying to combine two usually separate programs—cattle and sheep—in a single, permanent structure. Using Poldenvale-manufactured gates, railings, and handling equipment, along with found materials like railway sleepers, the result was half earthwork and half farmyard. Certain aspects of Price’s preliminary designs gave Sparkes pause. “Whilst from a practical point of view I can see no reason for the solid welling,” he wrote, “I must accept that for possibly aesthetic, or other, reasons, you feel it is a necessary part of the unit.”2 Mark Palmer replied gratefully. The points Sparkes made “had proved to be of great value,” and they hoped to consult him for further advice in due course.

-

Price was known to visit the Royal Agricultural Society’s Royal Show yearly, which was held at the National Agricultural Centre. See Samantha Hardingham, Cedric Price Works (London: Architectural Association, 2017), 507. ↩

-

C.S.J. Sparkes, letter to Cedric Price Architects. Unless noted, all text quoted is sourced from Cedric Price fonds document folio DR1995:0285:062:002. ↩

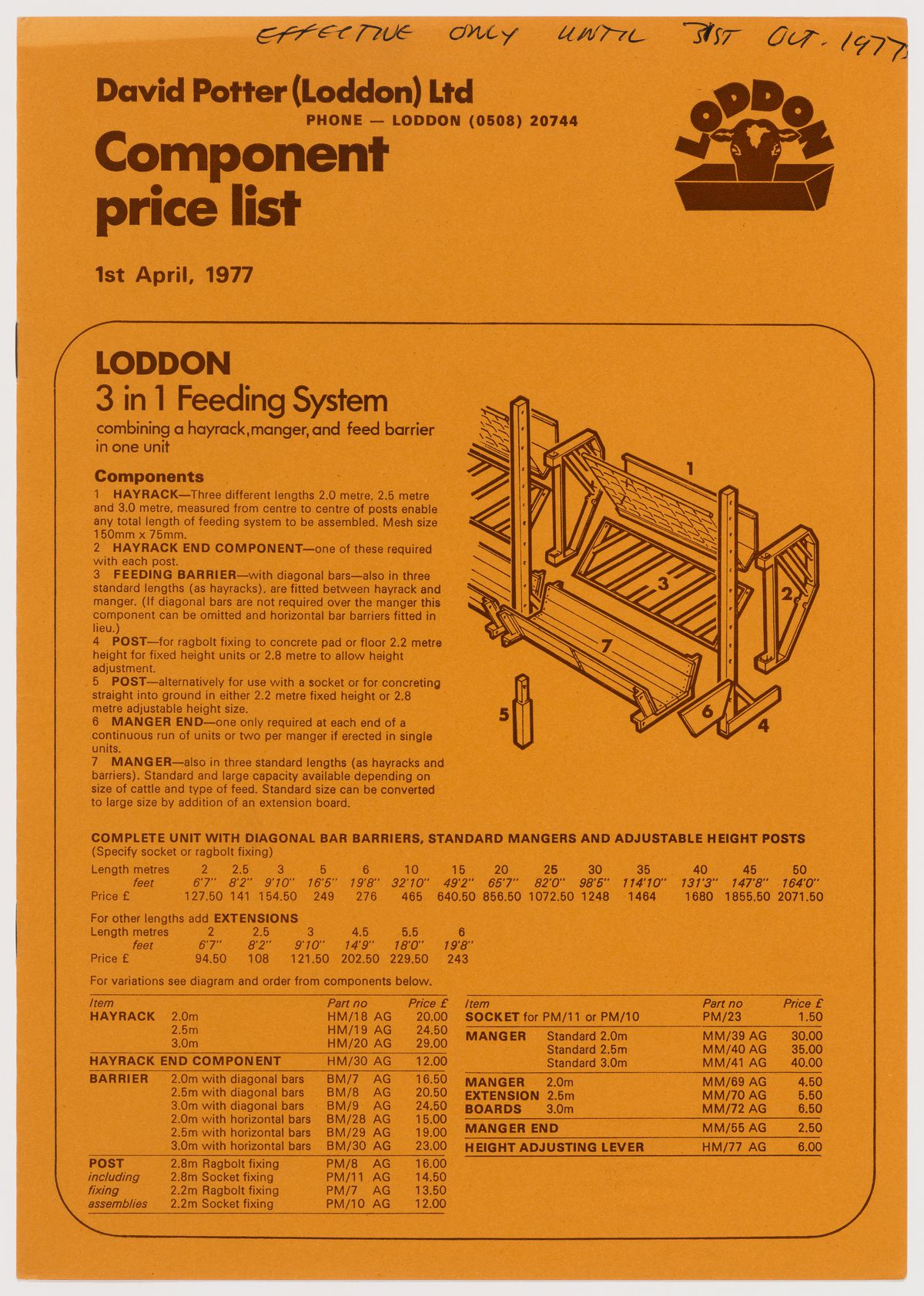

Price had great affection for the market—believing architects should pay attention to what real people desired, and that purchases showed this simply. But the market’s effects upon the English countryside were the subject of controversy at that time. The proliferation of small direct-supply businesses in England in the 1950s and 1960s followed intense postwar mechanization of agricultural production. As machinery outgrew traditional farm buildings, the government repurposed military technology for peacetime food production.1 The Agricultural Land Service designed a multi-purpose farm building with precast concrete components that could shelter spans of fifteen to sixty-five feet—far greater than traditional timber frames had allowed. Private manufacturing firms embraced and expanded this model. All over Britain, the family farm changed shape, and the landscape changed with it. The prefabricated buildings and equipment offered by Poldenvale, Stow, and other companies could be assembled with little professional expertise. These companies produced bulletins, newsletters, and promotional material alongside constantly-changing price lists.2 The rural built environment was ordered piecemeal from their pages. Traditional farm buildings that the new builds replaced, fashioned in the rural crafts traditions, were left empty: standing as storage, refurbished as living quarters, or left to decay. With their decline, a certain aesthetic idea of English traditionalism was put under threat.

The new farm buildings, with their corrugated asbestos siding and clumsy joints, were seen as an affront to both the old order and to modern good taste. They were deplored by architects, the only disagreement being about where to lay blame. The profession itself might even be at fault, weakened from an economic slump and resulting job scarcity. Architects were not providing inspiring alternatives. Calls were made by some for a “new vernacular” that could meet the requirements of the times; an agro-architectural style was needed.3 The farmer’s profit-driven tendency to “unwittingly desecrate the countryside” with these new builds was the subject of heated debate in the Architects’ Journal.4 One irritated farmer named Donald Pasfield polemicized “if there is one thing we farmers need more than a hole in the head it is high powered agricultural architects,” provoking a four-issue-long stream of rebuttals. “Take off your muck-coloured glasses, Farmer Pasfield, and look around you!” cried Robin Butterell, RIBA.

The Architects in Agriculture Group (AIAG) was formed in 1974 in response to these concerns about the decline of the rural landscape. Led by architect John Weller, this RIBA Special Interest Group published occasional papers and organized workshops and events relating to the architect’s role in the changing English countryside.5 Their 1977 seminar, “Farm Tourism: the recreational use of farm buildings,” argued for conserving farm buildings by finding new ways to make them productive in the blossoming leisure economy, retrofitting them as tourist attractions. In other writings they advocated the architect’s role as a consultant in the prefabrication process. The AIAG attitude towards existing prefabricated products was hostile. “Modern design seldom has any relevance to the quality of traditional building. It reflects only new industrial requirements based on low capital investment.”6 Though conservative in approach, the AIAG was not advocating a return to the past, since architects had never really had much involvement in rural architecture. Instead, they aimed to carve out a new role for the architect within this landscape at all costs, whether by preserving existing structures or building better new ones.

The chief complaint of the AIAG was the fact that the new agricultural landscape was proliferating outside the jurisdiction of the architect, yet market solutions to this were lacking. When architects substitute themselves for missing clients, practical problems can emerge—and clients for farm buildings were difficult to come by. Alistair McAlpine, with his independent wealth and casual interest in farming, could hire his architect-friend Cedric Price for fun. But the average full-time farmer, whatever his concern about the visual character of the countryside, could hardly budget a design consultant into his seasonal operating costs. So Weller and the AIAG turned to state actors. Their 1977 manifesto Official Architects Serving Architecture—An Appraisal appealed to the Department of Agriculture, Forests and Fisheries to create a Directorate of Landscape and Built Environment. Their demands were, among others, that “independent architects should be employed in matters related to national standards for farm building design,” and that “manufacturers of prefabricated buildings employ architects during the development of prototype design.” Faced with a “package deal” system operating with no clear need for architects, they aimed to reinsert the architect into the supply chain. To do so required them to identify what special qualities the architect brings to the table.

What were these qualities? For J. N. White, Design Council deputy director, the architect’s most valuable quality was the ability to balance contradictory demands. In a 1968 speech to the Royal Society of the Arts, he characterized the two demands placed upon the English countryside as “function” and “amenity”—two conflicting demands familiar to any designer. Function refers to the requirements of utility and economy; the most efficient route through the problem. At the scale of the land, function was the budget-driven decision to throw up a serviceable building—any building—for the needs of production and profit. If function brings short-term advantage, amenity brings “broad, long-term satisfaction.”7 The sense of stewardship and national pride that Weller and his fellows felt towards the English countryside is of this species, driven by a deeper interest in the quality of the environment and—perhaps—the quality of lives lived within it. Sparkes, with his comment that “aesthetic or other” reasons were driving Price to certain eccentricities in his designs, exemplifies the other tendency: in a firmly functional mindset. By White’s logic, agriculture needs architects because “…it is through skillful design that the demands of function and amenity can be reconciled.”8 The special skillset of the architect equips him to negotiate this compromise between pressures.

-

The scheme was carried out by the Agricultural Land Service, a division of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries under the Attlee government, and known as MAF components. The components were fashioned from Morrison table shelters and Anderson air-raid shelters. Agricultural Land Service, “Multiple-purpose Farm Building,” Architectural Design 20 (February 1950): 45; and John Voelcker, “Farm Buildings,” Architectural Review 127 (September 1960): 184. ↩

-

The quote for Westpen’s components increased twelve to fifteen percent during the development period of the project, between April 1977 and February 1979. ↩

-

John Voelcker, “Farm Buildings,” Architectural Review 127 (September 1960): 182. ↩

-

The Editors, “Farm Buildings and the Planner,” The Architects’ Journal 146, no. 5 (2 August 1967): 269; Donald Pasfield, “Meagre harvest for architects,” The Architects’ Journal 165, no. 9 (2 March 1977): 381; Robin Butterell, “Aesthetics of farm buildings,” The Architects’ Journal 165, no. 11 (16 March 1977): 479; Dirk M. Bouwens, “Lords of all they survey,” The Architects’ Journal 126, no. 12 (23 March 1977): 524; John Burkett, “Meanwhile, back on the farm,” The Architects’ Journal 165, no. 13 (30 March 1977): 577. ↩

-

Architects in Agriculture Group, Coleshill Model Farm Oxfordshire: Past Present Future, edited by John Weller (Birmingham: Royal Institute of British Architects: Birmingham & Midland Institute, 1980). ↩

-

Architects in Agriculture Group, Official Architects Serving Agriculture: An Appraisal (1977), 3. ↩

-

Noel White, “Farm Buildings Design and the Landscape,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 116, no. 5138 (January 1968): 99. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

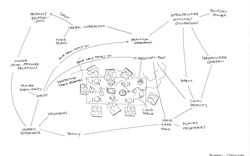

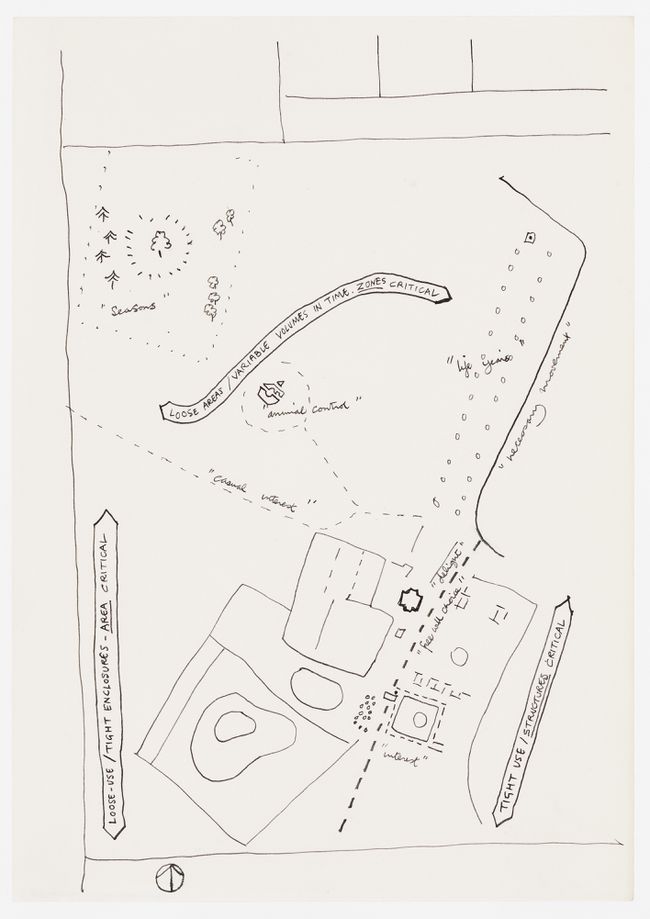

Cedric Price. Site plan showing zones for the Westgreen Amalgam, West Green House, Hartley Wintney, Hampshire, England, between 1977 and 1979. Cedric Price fonds, CCA. DR1995:0285:062:001:005:008

Price’s solution for McAlpine’s rural estate spared no expense. He produced two intricate models for the Westgreen Amalgam: of the adjustable aviary, which was partially realized on-site, and of Westpen. The Westpen model was moveable, with a variety of arrangements to show different uses of the site. The animals would be controlled by a series of gates, corridors, hurdles, and “crushes” (machines that immobilize cattle while they are being tagged or treated). Both sheep and cattle could use the pen at different times, taking different routes; the cattle-height gates would be modified with an extra bar for use with sheep. A staircase and platform afforded possibilities for human supervision. Over thirty schematic drawings were produced for the project, along with site-wide considerations of the rural timescale (200 years) and individual landscape elements. The drawings range from a sketch abstractly describing the wider Amalgam’s spatial and seasonal balances, to a flow-chart mapping the stages of the animal’s progression through the pen. Westpen diagrammed operations at the scale of the body for both animal and human users.

As a finishing touch, Westpen could be converted for less industrial needs. Aiming to provide “maximum enjoyment for observers/occupiers of whatever activity is current,” Price hybridized the productive function with a leisure component. For several days of the year, “particular sheep and cattle” would be sheared, dipped (with a chemical solution to prevent disease), weighed, and otherwise held and treated. The rest of the time, the railings and gates were packed away and humans could picnic and play around the peculiar circular indent and grassy mound, the productive site becoming a folly for human enjoyment.

Potentially a response to the contemporary debates Price followed around leisure and productivity, this move neatly sidestepped the problem of developing a ‘new agricultural style’ that could mediate between countryside pressures. In Price’s project, change of use over time allows a cordial separation between the territories of function and amenity. In fact, despite the faith White and Weller placed in the architect, few were drawn to take on this prickly and difficult task of negotiation. Efforts to bolster the architect’s presence in agricultural design soon dwindled and died out; the AIAG’s second and last occasional paper, Information sources for the farm building designer, was published in 1982. That Weller’s vision of a new rural career path for architects proved idealistic should not perhaps have been unexpected—the professional landscape was already quite crowded.

Price discovered this reality to his disadvantage when, in July 1978, the office received a bill from Mr. Sparkes for the sum of £68.04. Price’s surprise shows in his response to the fee: “Certainly it is not common practice and it was not drawn to my attention by yourself.” He saw Sparkes as affiliated with the manufacturer, not a consultant in a very similar position as himself. As Sparkes explained in his reply, he was a middleman that Price had unwittingly hired through Poldenvale, C.S.J. & A.M. Sparkes Developments Ltd. being a company of their own who “undertake various work for Poldenvale Ltd. and also some specialist work for customers of Poldenvale on a direct basis.” His services, including extensive comments by letter and phone, and drawing up a detailed map of the gate sequence, were not given for free—just as an architect would not do those tasks for free. He assured Price that the invoice would be cancelled should Poldenvale receive an order for the goods quoted. After a period of silence, Price paid up.

Corinna Anderson is a 2017–2018 Curatorial Intern at the CCA. We hold 37 drawings, 23 reprographic copies, 1 model, 0.07 l.m. of textual records and 0.01 l.m. of photographic materials related to Westpen. Price and McAlpine’s friendship also produced McAppy, the project that inspired our 2017 exhibition What About Happiness on the Building Site?.