Choreography is a good word for it

51N4E and Rural Urban Framework talk about dialogue

Joshua Bolchover and John Lin of Rural Urban Framework spoke with Irene Chin, Francesco Garutti, and Andrew Scheinman. The full version of this conversation will be published in an upcoming book produced in collaboration with JOVIS to accompany The Things Around Us.

- FG

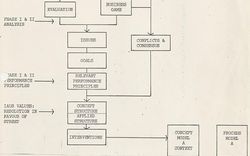

- Architecture for you is positioned within the—you’ve used the word “ecology.” You start by considering the uncertainties of site conditions, adhering to the realities of the place and engaging in a dialogue. You mediate between communities, between politicians and villagers, between large-scale forces and local constraints, between the vernacular and what comes from elsewhere. Only then do you set the conditions for intervention.

- JL

- Early on, we were in the habit of working with a network of donors instead of one single client. We weren’t quite conscious of the implications—we were just trying to do projects as young architects. We realized that by bringing together various funding parties and stakeholders where there is no obvious person in charge, the architect takes on a role of leadership. It’s no longer just the traditional one-to-one relationship of client versus architect. After our first project, this became our established way of working. It helped us expand the role of the architect.

- AS

- Is it a leadership among actors, or a director, or—is the design process in these new contexts more about mediation than building? Is design itself even central?

- JL

- Jörg Stollmann once told me about an orchestra that tried to make music without a conductor. That story really stuck with me and resonated with many of the experiences we’ve had.

- JB

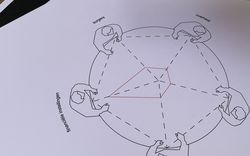

- Yeah, it’s sort of in between. I like that, “conductor.” But we’re also finding the band members too, right? It’s not as if there’s already an orchestra. We’re piecing it together. Or testing which instruments we need in order to put on a performance. It’s a good word. Others might be “enabler” or “curator.” I’m not sure. “Leader” is not quite the right word. It has to be someone who can speculate how the future might unfold but can then put the right people together to allow for that scenario to take shape.

- JL

- Maybe it is the balance between control and its opposite. And this leads to the idea of compromise and why it’s such a necessary part of the process of making architecture. We can understand compromise as a process that occurs when other people and agencies try to take ownership of the project. This should be encouraged.

- AS

- Sure. But what do we talk about when we talk about a lack of control? How do you decide what to control or not to control?

- JB

- It’s really about going into a project knowing that you can’t control everything. Which already differentiates us from a majority of architects, who of course want to design everything and control everything. The contexts in which we work—it’s impossible to control everything. Once you get to the point where you acknowledge you can’t, you are, on the one hand, liberated, but then you have to ask yourself: what is it that you want to orchestrate within the project? What can you control?

I think what we could control is the process, the organization. Where the light fittings are and how the wall meets the ground and whether there’s a shadow gap or not doesn’t really matter. It’s about trying to figure out what key element of the project we want to maintain. For a lot of our projects, we only learned this through the act of building. - JL

- We don’t necessarily measure ourselves by how much we’re able to control the site or the building process, which is what we’ve been taught in schools of architecture. Instead, we try to define the line between what we design and what we don’t. You could say this is an economical approach to architecture. Not just in financial terms, but in design effort. It’s about finding out where design is most effective and what other parts can be resolved more generically.

- FG

- So, for example, the local production of the brick moulds for your Angdong hospital project and the collective construction of the pavers for your Taiping village bridge project—these small design choices end up not only contributing to the local economy, but becoming devices for community engagement.

- JL

- Yes, we do engage builders directly. The moulds are built by contractors along with labourers from the village. Both groups contribute their own ideas, and we rethink our design process continually to incorporate these ideas. This engagement directly impacts and transforms the design itself.

- FG

- There’s a subtle difference between this sense of engagement and the idea of participatory design.

- JB

- We’ve never believed in this sort of participation through design. We come in with a degree of expertise as spatial enablers or choreographers of different actors and maintain that we have something to offer as designers. We test different methods of engagement—again, depending on the context—and scope out our control over the design. So, for instance, we’re going door to door working with a group of four families in Mongolia, figuring out what their needs are and how they can imagine their sites and plots evolving. But we’re not asking them to design. I don’t personally believe in that kind of participation as a process.

- FG

- “Choreography” is a good word for it.

- AS

- You’ve pointed out to us in the past that you sometimes forget in choreographing these relationships and having conversations with families that you actually do, in the end, make buildings. Sometimes you seem to play more of a mediating, facilitating role, with the buildings almost secondary to the relationships and networks you build on site. Sometimes, as with the As Found Houses project, you don’t seem to intend to build at all. So how do the buildings come about? If it’s not participatory in this sense—

- JB

- Well, what do you mean by participatory? It seems useful to unpick what these words mean and not take them for granted.

- JL

- It’s important for us to retain the expertise of design, the authorship of design, and to not pretend that other people have designed it. It’s about limiting our designs to a few essential things. We try to design projects so that the community can really take it over, transform it, and change it. We try not to over-program and to accept that things could evolve.

- JB

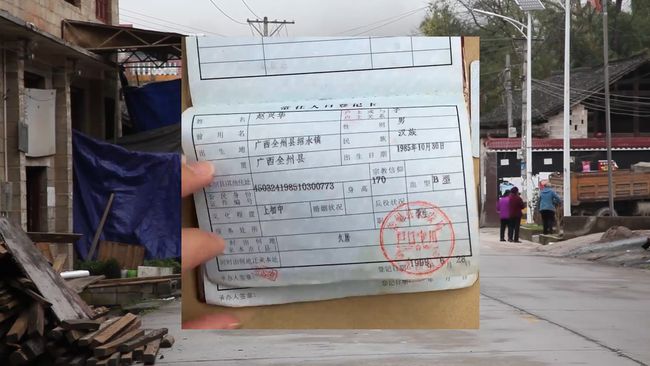

- We had two lessons of this. One was in China, when we were working on this school in Jiangxi, and the group that we were working with, the NGO, asked the children to draw their ideal school. They could draw whatever they wanted on paper, with only their imaginations, their creativity, and come up with whatever they thought their ideal schools would be. Thirty kids drew a generic, floor-slabbed school with a Chinese flag on top.

The other example is from Mongolia. We were trying to engage the community and asked them what their dreams were for these neighborhoods. And everyone just wrote “make the road better.” And for me, I noticed that part of our role is to be outsiders. It’s an advantageous position to come in from the outside and offer things that people would never have thought of before because they’re so contained within their own contexts. They only know what they see and what they’re familiar with. Part of our role as experts with our architectural mindsets is to come in and suggest something else.

- JL

- This is another way to interpret the local and the global. Maybe it’s important to be both an insider and an outsider, as Josh is saying. You look at all these things locally, but you look at it having seen other places around the world and able to see connections between them. Sometimes that’s our responsibility—to look at Mongolia and what’s happening there, but with an awareness of what’s happening in Latin America—to understand why it’s different and what solutions can be transferred and what solutions are irrelevant.

- AS

- So these same considerations, in some sense, apply universally across the planet?

- JB

- Somehow, we like to work with things that are familiar and normative but also quite other, quite strange, quite confrontational to their place or context. I think there’s something about the architecture in these places that has that kind of quality. It’s not completely of its place nor is it completely alien. It’s hybrid; it has duality.

- JL

- Our participation in these places is an attempt to allow them to evolve more naturally. It touches on this question of architecture without architects again. When the world changes very slowly, you don’t need designers, because communities can innovate according to their own needs and build for themselves. It’s an inherent part of our relationship with our environments and an inherent part of how communities work. Traditional communities are always innovating, but that innovation happens over a very long period of time.

Now, as the world moves faster and faster, we witness many places getting more and more fragmented. What we try to do is to create a new spatial cohesion. We try to stitch together aspects that have been fragmented by the forces acting on these areas. And we also try to create a cohesion between the past and future, between an abandonment of one way of building and the wholesale adoption of a completely new way of building. The communities we work with are interesting because they still have one foot in a certain cultural condition—they still hang onto the richness of these places—but they also want to speed up toward what they perceive as a modern condition.

There’s immense potential in working with these communities specifically because it presents a new possibility for how development can occur. We’re interested in how architecture works in dialogue with what’s around it. And so the combination of alien and familiar in building becomes a vehicle for an evolution of place that remains in harmony while adapting to rapidly transforming lifestyles.

Sotiria Kornaropoulou, Aline Neirynck, and Freek Persyn of 51N4E spoke with Irene Chin, Francesco Garutti, and Andrew Scheinman.

- FG

- Design for you seems to be a physical representation of a dialogue—a dialogical construction. Sometimes you’re the centre, driving the project, and sometimes you’re on the outside. Sometimes you’re coordinating relationships. Do you consciously reflect on this change—on the changing position of the architect?

- FP

- Yeah, for sure. For instance, the job we have for the World Trade Center in Brussels’s North District is just a percentage of the commission. There’s the main architect from Jasper-Eyers, a big firm in Brussels, and then we complement. The way for us to survive in this construction is to come up with a vision, a strong proposal, a new approach and therefore a new identity for the building. But we also think about how our proposal could work with a “business as usual” approach, how we could use construction methods or materials already commonly used by Jasper-Eyers. We think about what could be different, but also about what could remain the same. In that sense, we do think about the role we play. Or rather, about what the situation asks of us. So yes, it is strategic, what we do, and often about choreographing ourselves and if possible, others, along with the process itself. In that process, we act accordingly and pragmatically to see what can emerge.

- IC

- Tell us about how you adapt this role from large-scale projects like the North District and Skanderbeg Square to more intimate designs, like the tables at the Centre for Openness and Dialogue, the love seats in Skanderbeg, and Room in the City.

- SK

- This summer we were involved in a temporary intervention, a mobile forest, with the Lab North initiative in the North District, and it plays with this contrast between big and small. The extra-large sidewalks in the area make for all these blind façades, but they are also a huge reserve of space. Installing a lot of plants, a bit of water, some benches and tables can transform the experience of the place. You see people slowing down. Some take a seat, some hesitate. It’s something unusual in the area.

- FP

- Space can reveal how people want to behave. It produces certain conditions you respond to. But these examples are in spaces that don’t tell you how to behave. They don’t reveal those behavioral patterns quite so obviously. The love chairs are too big for one person and too small for two, so people decide for themselves how to manage their interpersonal distances. We can’t decide it for them.

Somehow discomfort can offer a lot of freedom. You’re not automatically reduced to a consumer. Discomfort allows you to take a position. This is a discussion we often have in our process: what kind of freedom does the design trigger? Freedom comes from not only from giving people convenient choices, but from putting people in a position in which it is up to them to choose.

- FG

- This gets us to a question about what you control or choose not to control. You select these things to allow for openness. You create an infrastructure for a sort of emotional proximity.

- FP

- Yes, and the way we work, it’s a constant struggle, but it’s a struggle that has become a strategy. We’ve often found ourselves in situations where we have to give up control and where we can’t design from A to Z, so we’ve had to become strategic about which things we choose to change. We look for small changes, for interventions or even disruptions that can colour everything else. With the love seats, there is other furniture in the square—concrete benches outnumber the chairs by a lot—but the chairs produce so much meaning that they start to colour everything around them.

- AN

- That’s why adaptability is so important. Take a project like the BUDA Art Factory. With such a small budget, we focused on the basics of what the building should offer: a visual identity from the street, smart circulation, and a range of different spaces. After it was completed, the project still kept transforming: the client changed parts of the building, adding to what we framed. Users build their own emotional connections over time.

- AS

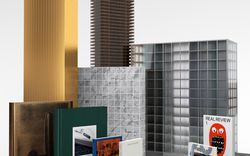

- Right, yes. There’s this clear emotional level, something about human connection, that you convey in talking about these projects. Your book How Things Meet even begins with a short story with fictional protagonists, and at the ETH lab where you teach, there’s a theatre set where students are invited to perform. Would it be fair to say that the way you think through and present these works, both to us now and to clients in process, is itself a strategy? Is it a means of coyly suggesting and exploring new ideas?

- FP

- How Things Meet is a very different story from ETH. How Things Meet came out of frustration. We didn’t know how to communicate our work in Albania. It also had to do with an ongoing discussion we were having in the office about the value of work. Johan and I never wanted to be dismissive of the parts of our work that have failed. We wanted to show these failings as something valuable, as an experience that you learn from. Those failures can be very disarming. But looking at a portfolio, you assume that everything shown is something you consider good. With How Things Meet, you get the fiction and then the timeline, and in this timeline, it becomes clear that the work is more about learning.

The story there was more about communicating what we were doing, including the messy or unresolved stuff. It was a way to start to relate the questions that came out of that complexity. - FG

- In How Things Meet you’re kind of looking backward, no? But you also use this narrative approach in process with your clients.

- IC

- Even with us, yeah. You sent us a proposal in the form of a narrative.

- FP

- Yeah, that’s true. I hadn’t considered that. A narrative is indeed also about trying to forecast an experience: it’s projecting that experience, imagining it beforehand.

- FG

- To me, it’s about curating the conditions for openness and dialogue and about making a kind of design infrastructure that sticks around after you leave. About not overdetermining the future of a place and instead modifying the conditions, allowing the transformation to take place without you.

- FP

- We want to enable situations, to do one thing in the hope that a second thing will follow. I have a feeling a lot of architects only focus on that first thing and that’s where their design process stops. But our work is not about giving that kind of order. It’s about creating connections, trying to trigger something.

- FG

- I was thinking about the idea of curating a building.

- AN

- We do have that kind of a relationship with the BUDA factory. We’ve followed up and have changed the building and modified it, made new openings and new connections. And it’s interesting because you start to structure these changes collectively, with the clients and the users, to build a preciousness and identity. You discuss together what to respect and to keep and what to allow to transform according to its daily use.

- FP

- The TID tower is the same. It’s very mathematical, its façade seems to be coherent, but really, if you look at it, the building is ad hoc. Only two small things are defined, and everything else is negotiable. There is the shape of the tower, the space of the golden cupola and the urban void of the galleria. Everything around these interventions has been malleable. In retrospect, it is amazing to see how much these three shapes have been respected and how much the things between them have been changed. There’s room to play around these things. You define a timeframe in which certain things hold and others change. Architecture has this capacity to structure different timeframes like this, and at certain moments it can even stop time.

- IC

- Are there limitations to participatory processes like these?

- FP

- In Dutch, dialogue is tegenspraak—something like “counter-speech,” which has a certain resistance baked into it. It’s true that participation has this kind of “go with the flow” notion attached to it, the idea that you should make people as happy as possible and talk as much as possible. Of course, there’s something good about it, something noble. But dialogue is also about resistance and about silence. When you don’t speak, you can listen to what’s not being said. The word participation, for me, too often treats citizens like customers or consumers: their desires should be met, and the best design is the one that meets the most desires, or worse still, leaves everyone in their comfort zones.

We try to do two things: one is to understand what a person wants, their ambitions and their capacity for complexity. The second is to take responsibility for exceeding that situation, to bring it to a higher level. In participatory practice, this doesn’t always seem like the goal. - SK

- I think the best dialogues have people commenting afterward that what we arrived at was not at all what they expected. We ourselves are also surprised when something new emerges. Not every meeting gets there, and it does take a lot of energy and openness from everyone, but when it happens it is something magical.