An Undisciplined Practice

Julian Schubert, Elena Schütz, and Leonard Streich of Something Fantastic in conversation with Francesco Garutti

- FG

- Reflecting on context today means more than ever reflecting on an extended range of agents and agencies which intersect with the practice of making architecture. It involves, I think, investigating the ecology of the contemporary notion of practice—the people, tools, policies, economies, times, and scales with which the architect interacts, but also the position of the architect within this expanded system. Different positions mean different forms of practice.

You have always been working in-between disciplines: between the design of identities, research, book making, architectural practice, and curatorial work. And everything began when you set up your office and released a statement framing your plans that read “What is relevant today? How can we be relevant within the discursive space?” - LS

- What drove us more than our relevance as architects in that specific moment in 2009 was how the relevance of things became fluid and the status quo could be questioned due to the financial crisis. Organizations, firms, and institutions were evaluated for their systemic relevance. Suddenly it felt like things that used to be untouchable became changeable, or even dispensable.

- JS

- This brings to mind a cover of Domus magazine—directed by Joseph Grima in those years—that we designed and unfortunately was not printed. It had just one statement on it, which read “Long Live the Crisis,” meant in a positive way. It felt like at that point everybody had understood, that “before,” meaning before the financial crisis, had been an absurd moment in history that obviously we couldn’t continue: with endless growth, exploitation of natural resources and of people, ever bigger buildings, ever faster cars, and so on. The state of crisis as a condition that makes you deal thoughtfully and consciously with all resources seemed rather natural to us. Growing up in the 1980s with parents active in the environmental movement, this narrative was present from our childhood on. In that moment we felt like something opened up and there was space to reinvent—at least for ourselves—how we could contribute to a better world, by practicing architecture, by using the tools we learned, the knowledge we gained, and the ideas we had developed in our architectural studies.

- FG

- It’s interesting that now—from crisis to crisis, from 2008 to 2021—we can return to the meaning of the word “relevance” in a different way. In a moment in which financial logics have swallowed up the potential for architects to be influential in transforming space, often leaving as the architect’s sole role that of decorating real estate development with a bit of well-being or green strategies that are paradoxically unsustainable, we should really think how an architect can be relevant. How did you position yourself in this sense?

- LS

- I guess one very practical effect of it was that we were branching out into three directions at the same time, making first steps into teaching—in architecture courses and programs—, doing graphic design—mostly for others—and doing architectural, or let’s say spatial, projects. This diversification has been present in our practice since then, and it allows us to work within the system and outside of the system at the same time. In order to work on the system you need to be in the system, as Freek Persyn puts it. The risk is that you become the status quo you wanted to change, but so far we are managing to avoid this relatively well, even as we leave behind the status of a “young practice.”

- FG

- In constantly fluctuating between different approaches to space-making practices you arrived at defining an ambiguously interesting position. For example, in your statement about the Disillusioned Office project—an office renovation for the digital industry association Bitkom in Berlin (2016–ongoing)—you mention considering procedural interventions as products in and of themselves. I can also think of your design for Perret Schaad’s fashion show in 2014, where your spatial intervention was to select a place for the show and to define its functioning and procedures, instead of designing it.

- JS

- In both cases we tried to avoid actually building something, simply because we felt there were better ways to solve the problem, or to satisfy the client’s needs. It might seem obvious, but it is uncommon for architects not to propose designing a building or something built. Not least because that is what they are usually asked to do. In the case of these two projects, it was us who had to question if and what had to be built. In the case of Bitkom, instead of designing an interior for a new office space, we put an emphasis on organizational interventions and the redefinition of policies that then manifested in comparably minimal spatial interventions. In the case of Perret Schaad, instead of designing a show setup we proposed using an existing space.

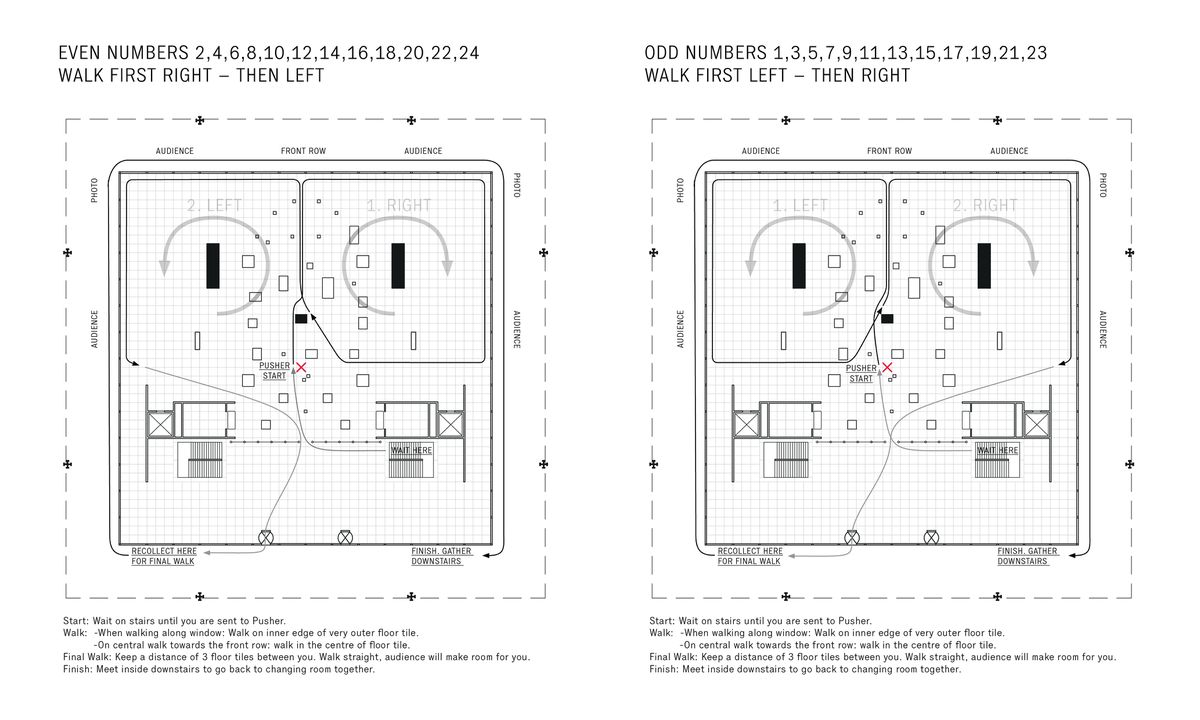

A fashion show lasts 10 minutes, and we were driven by the horror of all the trash that is usually produced by a temporary event like that, so we were looking for ways to avoid it. This is how we ended up looking for existing spaces that already met our criteria for an ideal show setup, and found it in Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie. Starting from there, we developed an informal, minimally invasive show concept: the 25 models bought tickets to visit the galleries, entered the exhibition on view during opening hours, and walked along the glass facades, fully complying with the museum’s house rules, while the invited crowd watched from outside. In that sense it was also a comment toward the ridiculous front-row culture, because there was only a front row, and an accidental passerby might have had a view just as good as an invited VIP. - FG

- You approach was curatorial.

- ES

- Right. Although, one could also just call it planning. Take the Perret Schaad show as an example: we may not have designed that space, but we defined everything around it. Instead of deciding on shapes, proportions, and materials, one has to design a strategy, a schedule, a choreography. Like “traditional” architecture, one has to draw an image of what could be and convince people that this will not only work, but it will look and feel good.

In this case the key component of our job was to convince the designers to take a risk, to use a public space without having had the chance to make sure this was allowed, to be prepared for multiple outcomes and reactions, and to some degree to deviate from the usual way of doing things. The show, for example, had no music playing. If you have ever been to a fashion show, this is hard to imagine. What made it easier for us was that the budget was very limited. So, the clients didn’t really have much of a choice but to follow us into new territory—a bit of a similar momentum to that of the crisis as a driver for change.

- FG

- In your practice you have recently been using and “taking care” of another milestone in architecture history, Álvaro Siza’s Bonjour Tristesse building.

- LS

- The building is famous in Berlin for its graffiti that has been there for more than thirty years, as well as for its slightly curved roof shape. What most people do not know is that it has a very generous roof terrace that—because of the curved wall surrounding it—has a very cozy, yard-like atmosphere. It reminds us of Le Corbusier’s destroyed yet legendary Beistegui penthouse in Paris, with its exterior-interior atmosphere. The owner of the Bonjour Tristesse building asked us to design a canteen on the roof as well as one of the apartments in the building.

- JS

- Actually at the beginning we weren’t commissioned to redesign the roof nor that one apartment—we were just hired to design a staircase installation. But when we realized that the owner, in his attempt to make the roof accessible again (it had been closed in the 1980s because of security risks) had ended up with a very conventional roof terrace decoration, we intervened. We suggested making a space for everything the owner wished could happen on the roof—dancing, drinking, being together—without destroying the open character of the place. Part of the deal with the owner was—as we wanted to “take care” of the roof rather than design it—to approach the project by asking “what would we do if this was our roof?” And that question has guided this work: we have kept the spending of resources—both time and money—to a minimum, and we haven’t asked for a honorarium but we can use the roof as if it was ours. The deal with the apartment is the same. The owner doesn’t use the apartment very often, so it’s also our guest apartment now. In the long run we’d like to turn it into a residency for people working in Berlin on cultural or technical projects related to care and nature. With the roof we have the same ideas, imagining that it could become an event and performance space with a group of young curators, to open up institutional borders and social bubbles.

- FG

- In the last thirty years, the real estate market in Berlin changed dramatically—from that fertile undergrowth of dwelling possibilities of the 1990s to the speculative environment of our days. But in the last ten years, cohousing projects led by architects have started to appear within the concept of the “Baugruppen,” in which the architect acts as a developer. What does this mean exactly, and how has this new phenomenon affected your approach toward practice?

- LS

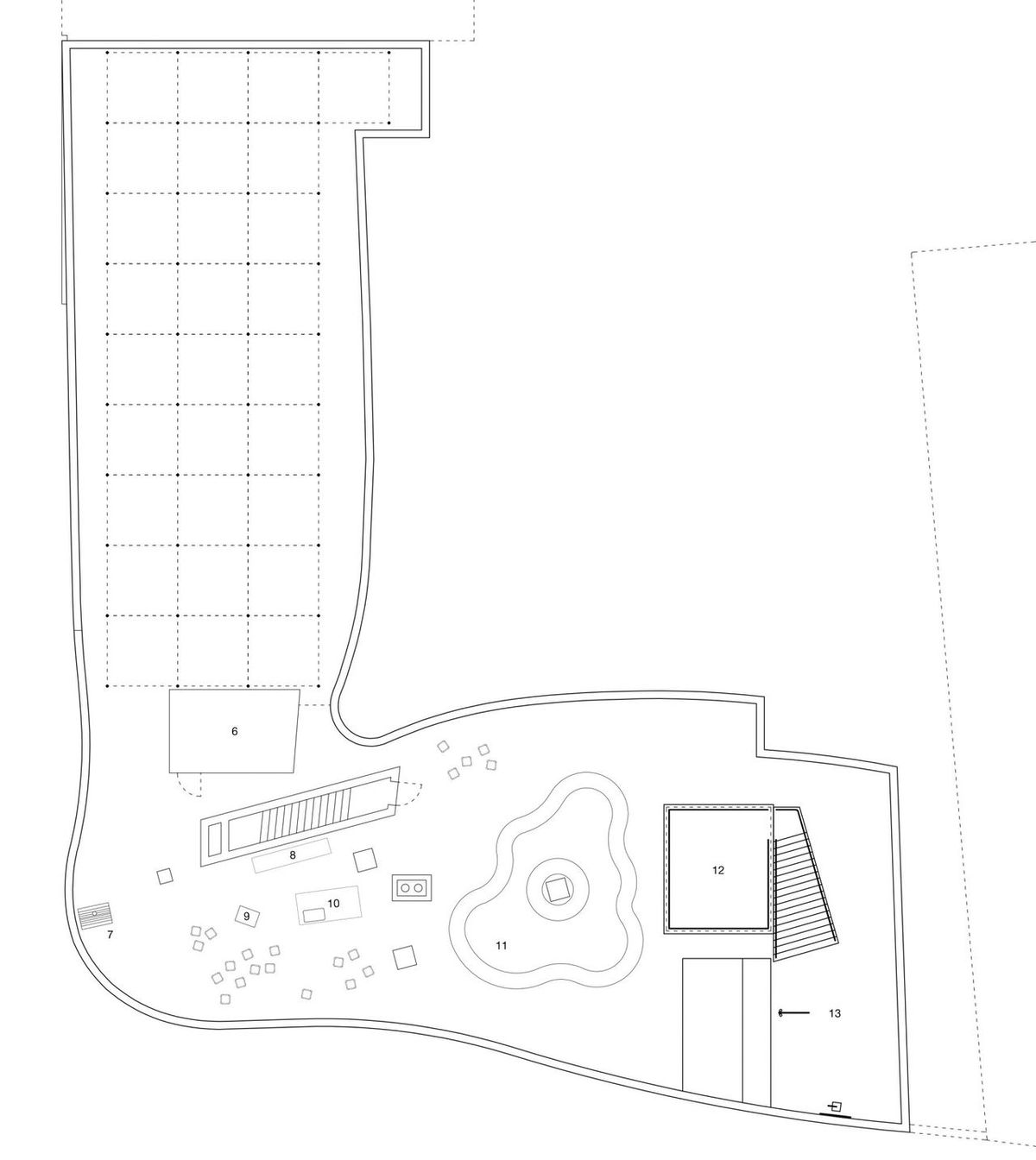

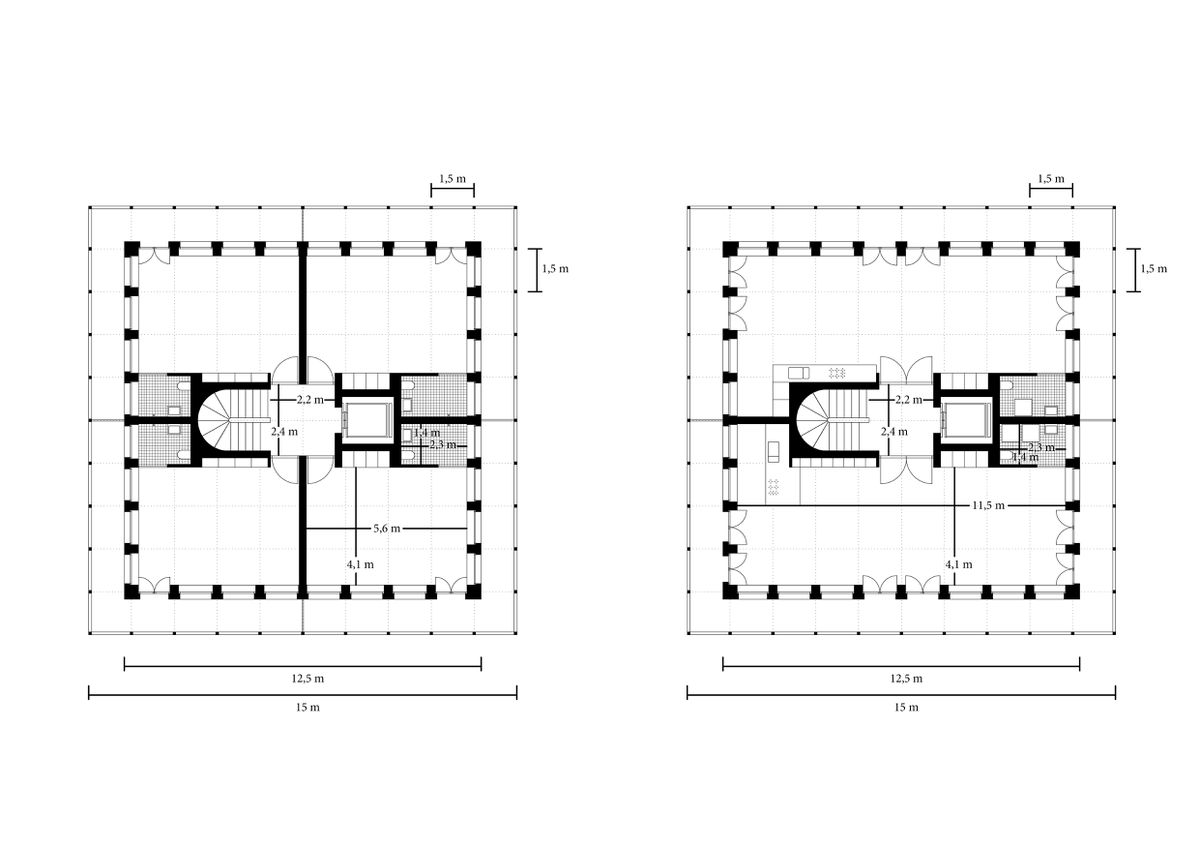

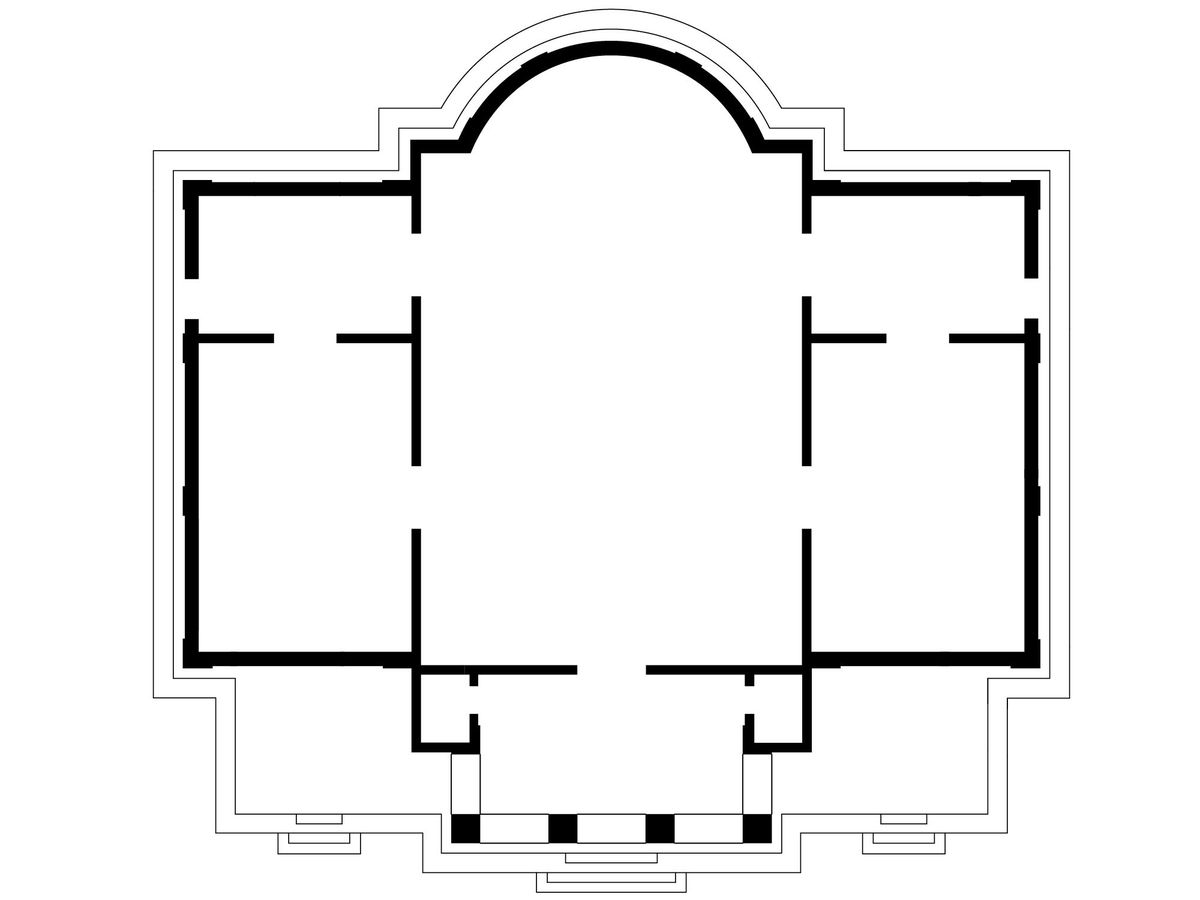

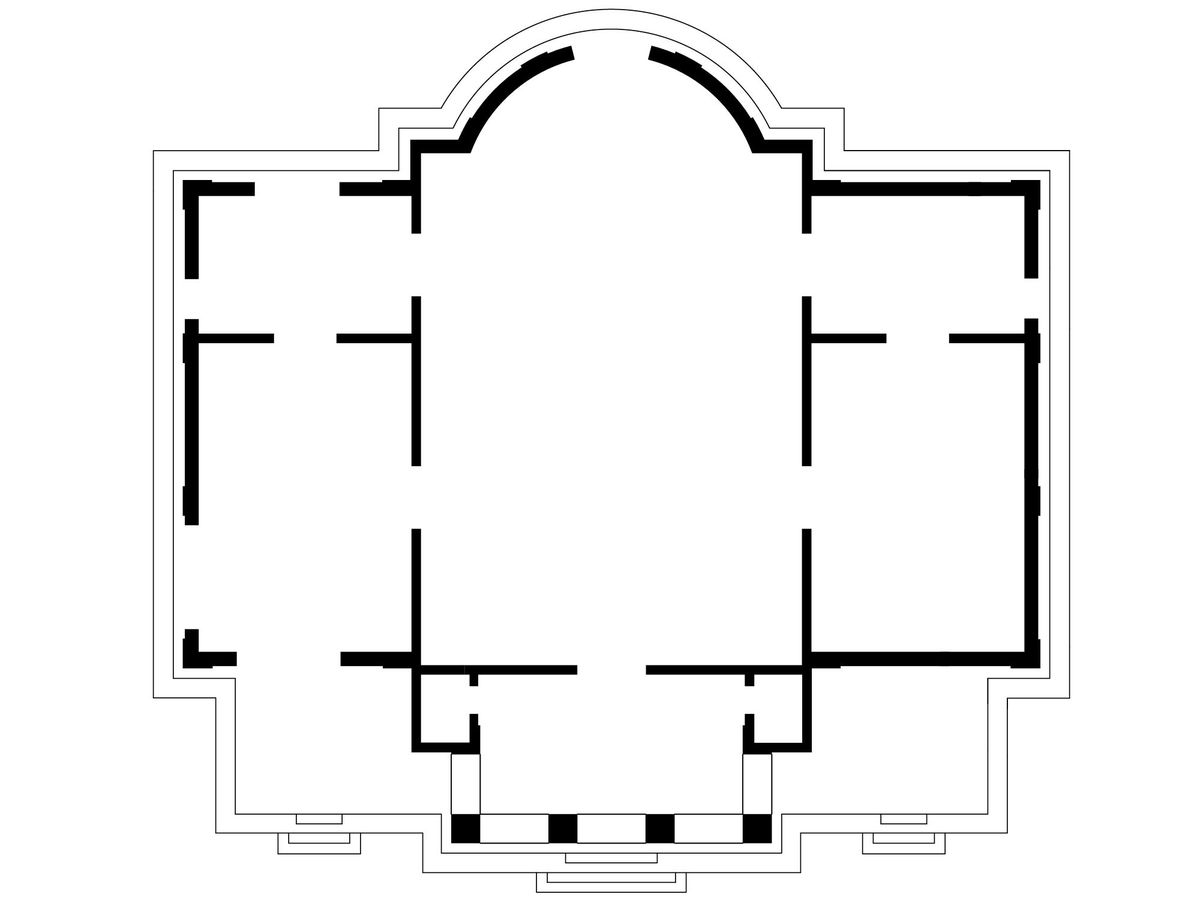

- We see a great potential in alternative ways of initiating, funding and operating buildings dedicated to housing. Not only for individual dwellers, or for the quality of the architecture (although these are good reasons) but also for the way that the city is developing in the long run. We started an initiative called Stadthausbauverein that concentrates on realizing a building type that we think would be beneficial for a more diverse, inclusive, and thus more sustainable, urban development. The main characteristic of this is a clearly formulated difference between the front and the back of a building, and, parallel to that, an internal structure that separates public and private spaces. The front, facing the street, is the loud, public, social side, and the back, in a typical Berlin block facing the backyard, is the quiet, private side. The building becomes a mediator, eventually enabling the best of both worlds to come together, without colliding.

- FG

- What other projects are you working on that try to reconceive and design new logics or relationships between the different actors intervening in the building system?

- ES

- There are two aspects of our work that we are particularly excited about right now. The first is policy making, or—to formulate it in a more general way—everything that is not physically built, but that still has a great, and potentially bigger, impact on our environment and how we are interacting with it. There is a direct connection to 2008 and how the way we looked at things during the crisis changed the world more than anything else. I think it can be very powerful, fast, and efficient. And I think there is more space for design and architecture-related skills in it than one might think.

The other thing is finding ways to be involved in projects very early on—earlier than the architect usually would. Either by developing projects together with a client, helping to shape the brief, the direction, the short-, mid-, and long-term goals, or by becoming an initiator, a developer of your own project, and setting the parameters oneself. This would also allow for more reuse and non-building approaches than what you are usually able to do as an architect, working within conventional models.

But we also realize that this is much harder and less attractive than it sounds. It comes with working on a project without being paid and without knowing if the investment will ever pay back, and talking to people who have not necessarily been waiting for you and your ideas. We have been doing this for five years now with the Constellations House, which is a building type that, due to flexible connections between the individual rooms of each unit, is open and versatile in accommodating various constellations of users within the building. It caters to families who experience varying spatial needs over the course of decades, to people with special needs, to short- or long-term constellations of several groups or individuals living together. It is rooted in the believe that living together doesn’t work without sufficient privacy, and in the ambition to combine comfort and quality of life with efficiency.

Efficiency in this case is what makes the project sustainable. We can build “greener” with technical efforts and improvements, but as long as we do not use the space we have built more efficiently, it won’t get more sustainable. It would be a rebound effect like the one we see in the automobile industry, where energy savings enabled by more efficient engines are eaten up by ever bigger cars. We strongly believe in concepts that allow for an adequate use of space over a long time, and would love to see it built and inhabited within a few years.

- FG

- How do you manage to get involved in a project at an earlier point than usual? Have you been able to apply this type of strategy?

- LS

- The renovation of the digital company Bitkom office building in Berlin could be a good example. We allowed ourselves to fundamentally question the brief, and that again allowed us to come up with a much more minimal physical intervention than what the client originally had in mind.

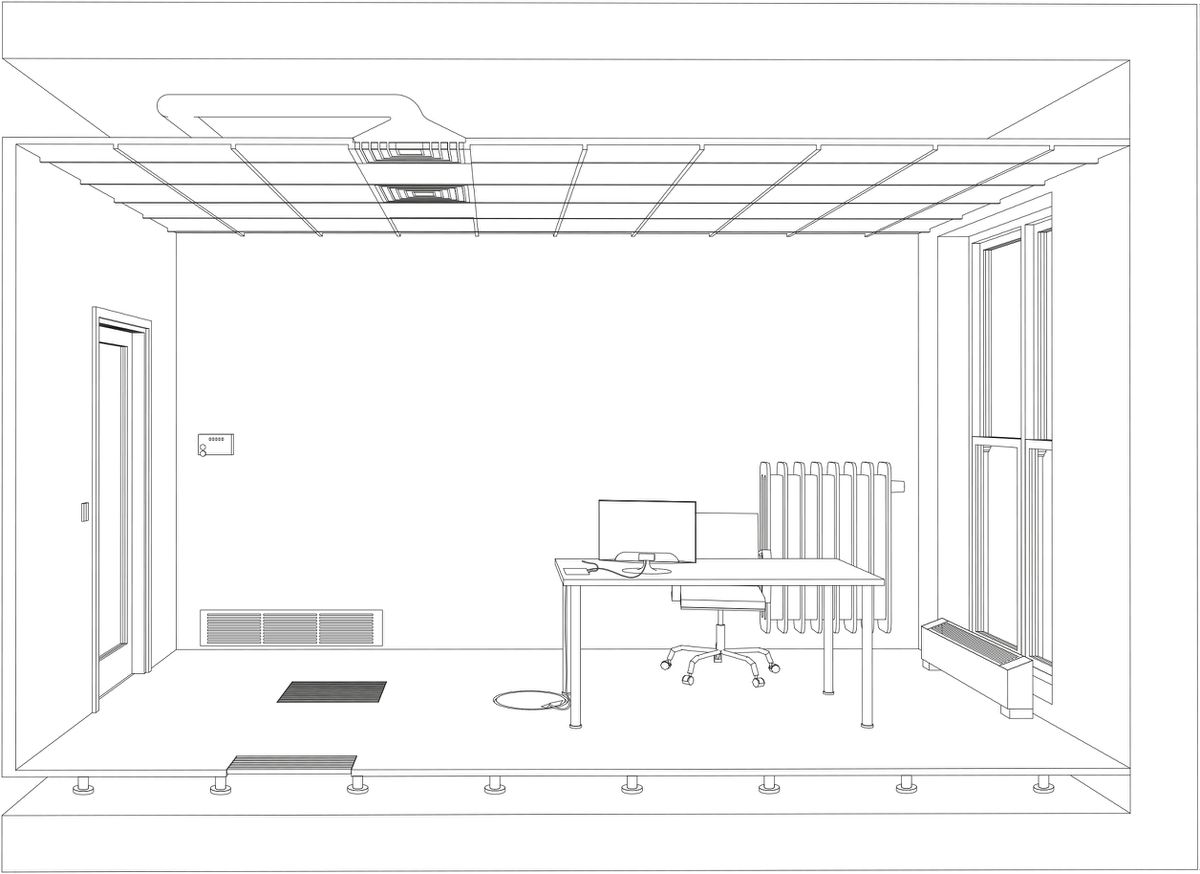

Initially we were shocked and then fascinated by how “normal” their space looked. This led to the idea to treat Bitkom’s office as a prototype with which to investigate workspaces today. Starting the project off with a general study also brought another great benefit with it: it provided us with a much wider perspective to not only look at the client’s spatial needs, but to take a closer look at how they work, and then to propose—first very generally, then more concretely—different strategies and ways of organising and structuring their operations. Only then we started to think about how that could be reflected in a working environment. I think it helped the client to be more open, and it helped us to convince them, for example, that they didn’t have to move and that they could achieve everything they wanted in their existing spaces. For example, we very bluntly presented a map showing all the gyms in their vicinity to argue that there was no need for a gym inside their office.

- JS

- The goal was to change as little as possible and to avoid “redecorating” the whole space in response to the image that the firm wanted for itself, only for it to be replaced by an updated, more contemporary version in five years. We wanted to break through this cycle. This goal was, for us, even more critical as we felt like this office was one of many, and it could serve as an example for many other firms in many other spaces. One of the biggest questions that we have to deal with, not just as architects, but in general, is how to better use what already exists.

So after having completed the organizational study Über das Arbeiten heute [About Working Today] with futurologists Ludwig Engel and Stefan Carsten, we translated our concept into a spatial design aiming to minimize the turnover of materials in the process while improving future ways of working inside the office. By clearly marking where the office space started and ended, with very different surfaces and material treatments, we created a situation that would distill the office to what it really is: a pragmatic built-in structure with wood chip wallpaper, suspended ceilings, and carpeted floor. - FG

- I would like to continue discussing this idea of spatial contribution based on a constitutional—and not only superficial—idea of sustainability. Your capacity to be radical is always shaped by the intention to tackle the structural components of a project. The example of your intervention at the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennial in 2016 follows these lines.

- ES

- In this case, we proposed simple openings in the pavilion walls, to express the accessibility and inclusiveness of Arrival City neighbourhoods as studied by Doug Saunders: neighbourhoods that become catalysts for people arriving and successfully settling in a new environment, giving immigrants the possibility to integrate both socially and economically.

- FG

- Sure. But in a way that project also speaks to me about how many architectural operations inhabit the space between curating the city and actually designing it. The format of your office highlights how interesting it is to explore the roles of spatial practitioners that are active parts of different processes related to space making besides the design—policy makers, urban curators… Even in Prospect One in New Orleans (2008), a large-scale exhibition structure somehow became a form of masterplan for the city.

- LS

- We like to go back and forth within a certain space, and I think this constant oscillation is our way of staying on track. At one point we started to call our practice an “undisciplinary practice,” not an interdisciplinary practice, and we are not an emerging office but an alternative one. We are not standing between the disciplines—our discipline is architecture. Yet not everything we propose is a building.

- FG

- Definitely. In this sense, 51N4E’s window proposal in the context of the Skanderbeg project in Tirana raises important questions. The process of negotiation with all the land owners and private parties facing the public space of the square in order to keep the space of Skanderbeg open, accessible, and connected with all the major institutions budlings facing the square was so complex. During the conversation with the National History Museum—whose windows directly face the open space of Skanderbeg—one of the proposals by 51N4E was to change the shutters and the curtains of the Museum windows in order to create a direct visual connection between the Museum and the square: between this museum representing the history of the country and the main public space of the capital of Albania, designed to help redefine a new sense of national identity.

- FG

- How would you define that proposal in that specific case? An architectural gesture? A curatorial proposal? An artwork? A suggested institutional policy? I think we are more and more in need of radical gestures like these ones, which are very simple but structurally transformative.

- JS

- Yes. As you said, we’re interested in solving things structurally: whether this is about policy, economic models, or space. In this sense, we have a rather classical attitude. There is one more project we are working on that I would love to mention to illustrate this: The Architecture Placement Group, in reference to the artists placement group that existed in England in the 1960s. The idea was that artists are placed in companies or institutions to work with the material and resources of that organization. For example, if there’s a metal-processing company then maybe the artist can get material for free and the mutual benefit would be that the company would enable research and open experimentation.

What we like about this idea is how it very concretely and directly translates something that we have been thinking about lately regarding the long overdue transformation of how we process and consume resources: the potential of proximity and the danger of distance. We find ourselves in a situation where we know we should do many things differently and that our actions have big consequences on the environment, but it is hard to understand what these are, and it is hard to know what is right. One possible way to approach this, in our opinion, is to bring things closer to our lives, to (re-)introduce things that are connected to us, that sustain and enable our lives, back into our habitats; our cities. This is a political and urbanistic scenario we are currently developing and calling “All-inclusive Urbanism”: get to know to how things work, make them part of our lives, find ways of working with them. Eventually, simply making them more sustainable from within.

This interview with Something Fantastic was conducted in the framework of the exhibition The Things Around Us: 51N4e and Rural Urban Framework, for which they conceived the graphic design.