Cuddling Rooms, Body Banks, and Collab Houses

Giovanna Borasi on new needs for architecture

The relation between society and architecture has always existed. Societal transformations have inspired architectural interventions to house our rituals, norms, and cultural patterns: architecture mirrors back to us our collective values. However, the rate of transformation undergone by society and architecture are no longer in-sync, leading parts of contemporary life to be misaligned with the spaces it occupies. Other times, architecture has been instrumentalized in perpetuating and embedding inequalities into our built environment. In all of this, we could end up living in spaces framed by societal values that no longer represents a shared vision of who we are.

The built environment conditions the ways we live, so how could we imagine for architecture to become a more attuned platform for society to exist? A real act of listening and a continuous search for sites to intervene can allow architecture and the built environment to respond more aptly, and at times anticipate, our changing set of needs. To do so, it is crucial for all the actors—not just architects—to constantly observe how society evolves. Not in an opportunistic way to satiate the latest market trends, but instead done as an act of care. Society is changing, how will architecture respond?

Solitude

In January 2018, British Prime Minister Theresa May created a new position in her cabinet, the Minister for Loneliness. Symbolic in gesture, it pointed to a growing concern over the state of chronic loneliness embedding itself into our societal fabric; with public health experts deeming it a looming epidemic.1 Unlike gauging the health of our economy, no metrics exist to measure the strength of our social bonds; an exact picture of our current moment remains murky. Countries globally have begun examining loneliness, as our present iteration of cultural patterns have created the conditions for us, aided by architecture, to grow apart.

One of the first acts from the British Loneliness Minister was partnering up with the Royal Mail, asking postal workers to check-up on those who maybe lonely during their usual delivery rounds. Mail carriers speak with individuals and offer information on how to access support networks. But this new practice immediately raises spatial questions: where will they talk? Do they have a comfortable space in front of their door for this simple encounter to take place?

Scarce from our daily social lives is the element of chance encounters. The slow erasure of liminal and intermediate spaces—corridors, storefronts, halls, mezzanines, etc.—have corresponded, whether directly or indirectly, with a societal drifting apart, a fraying of our social bonds in the absence of these spaces. The only ones who seemed to have kept these spaces are tech companies in Silicon Valley, guided not by creating a sense of community, but informal spaces used to generate and extract profitable ideas.

Perhaps it is the demand for spatial efficiency of the real estate state, the increasing desire for more privatized spaces versus shared amenities, a want for a more safety in our physical environment, the intensification of digital space in our daily life, or the obsession with ‘rooms’ with our current generation of emerging architects that has caused the erasure of intermediary spaces from architectural plans. The only ones left are the those functionally needed, such as elevators or waiting rooms in doctors’ offices and hospitals. In both spaces, conversations are now marred with suspicion and discomfort: each space is re-ritualized with occupants carefully choreographing their sightlines to never meet, eyes darting downward to the ground. In short, these spaces are avoided.

-

Sarah Marsh, “Combat Loneliness with social prescribing’ says Theresa May,” The Guardian, October 14, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/oct/14/loneliness-social-prescribing-theresa-may ↩

In most cities, the ground floor and lobby of housing complexes have become efficient spaces for distribution. If there is a concierge, it has been transformed into receiving and holding Amazon packages—some condominiums in cities, like New York or Milan, have installed smart technologies in their lobbies to notify homeowners of deliveries and have equipped rooms with fridges for food delivery.1 Once a site to welcome, talk, and check-in on each other’s has further become more overtly a security station, where social engagement in the space is shaded with a feeling of uneasiness.

Reflecting on the grand lobbies and mail rooms of Mies van der Rohe’s towers, which once read as spaces of luxury, could now be read as having been conducive towards building stronger social bonds. The ambiguity and undefined nature of these spaces fashioned an appropriate setting to nurture new relationships and entertain casual friendships, which are important facets to our social health. Regular interactions with those on the periphery of our social network make us feel tethered to a larger community, but the gradual erasure of unprescribed spaces from our architectural lexicon has left us with less fertile ground.

-

Paola Dezza, “La casa ai tempi di Amazon con il custode digitale,” Il Sole 24 ore, February 20, 2019, https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/la-casa-tempi-amazon-il-custode-digitale-ABnBicTB ↩

Architecture is the mise-en-scène in which our social lives unfold, discretely but actively shaping our social interactions. So, how can architecture care for its inhabitants in spatial terms?

More and more we witness the birth of new forms of improvised spaces to cope with isolation and loneliness, with makeshift flexible structures holding open a space to re-socialize architecture to our changing needs. Cuddling rooms—a soft architecture filled with couches, covered in cushions, and draped with blankets—welcome strangers who are there to be held or cuddled in a non-sexual manner. Research on cuddling shows that it releases endorphins, dopamine, and oxytocin which helps reduce stress and blood pressure; enables better sleep; improves communication between couples; and increases overall happiness and well-being.1

-

India Morrison, “Keep Calm and Cuddle on: Social Touch as a Stress Buffer,” Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 2,(2016): 344–362, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-016-0052-x ↩

Nevermore than now, has our reliance on digital technology to fight physical isolation been as high. This shift in living patterns opens-up a receptibility to new forms of digital intervention into the most personal aspects of our lives. Taking a section of our contemporary moment, we see the emergence of smart-homes that emulate behaviours of companionship by being able to talk with its inhabitants, or becoming an interface for families living apart to check in on one another. While there is a push for new spaces where touch is deemed acceptable, there is a growing offloading of care to machines. As baby boomers enter elderhood, the healthcare system will require a larger number of workers to meet an increased demand of care; robots are being developed to help meet those needs. However, with increased capabilities, will these new technologies be applied in our most intimate and vulnerable moments: will they be used as a way to entertain, to dole out medication, or to even accompany you while you die alone.

Love

Questions around love, relationships, and family have predominantly circled around the image and narrative of the nuclear family: man meets woman, man and woman get married, man and woman have children, and so the story went. But on the fringes of these images, have been non-traditional families that have overtime slowly moved their way into mainstream consciousness, fostering a growing acceptance amongst society: open relationships, ethical non-monogamy, polyamory, same-sex marriage, three parent family, single parenthood, co-parenting, singletons, child-free movement, chosen family, etc. Today, we could consider the traditional family as just one of the many possible permutations: approximately 1 in 4 households in Canada are made-up of married couples with children.1 Yet, our institutions, laws, policies, and especially the way we build have lagged in recognizing new expanded definitions of family and companionship that have implicated our spatial realities.

For our housing stock to best meet changing societal conceptions of family, there needs to be an openness and acceptance to build for non-traditional families and relationships. How could we design and think of spaces for nonnuclear families to support in our new societal settings?

In a suburb just outside of Berlin, a traditional house is now occupied by nine young professionals and one toddler, who are growing their lives together. It is motivated both by a shared sense of kinship and around issues of affordability. In their search for a shared home none acknowledged new forms of intimacy in their floor plans: too many separate kitchens, bathrooms, and not enough shared spaces or privacy. By pooling their resources, they were able to rent a house, otherwise several apartments in one rental building would have been required. However, a simple redefinition of spaces combined with a renegotiation of social roles render this former single-family home as a testing ground for new ways of forming a family. From the basement to the attic, spaces formerly accommodating a luxurious version of nuclear family life, now house a gradient of intimate lives and varying work arrangements within this close group of friends: the home cinema has been turned into an office, the lofted bed of a teenager into the toddler’s home and play area.

-

Statistics Canada, “Private households by household type, % distribution 2016, Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 Census – 100% Data,” Families, Households and Marital Status Highlight Tables, % Distribution 2016, accessed February 23, 2021, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/fam/Table.cfm?Lang=E&T=21&Geo=00&SP=1&view=5#shr-pg0 ↩

The unaffordability of housing, cost of living, and inability to independently build equity through real estate has created a growing receptibility to non-traditional forms of cohabitation. As a result, new digital tools are emerging to bring unlikely groups of people together. Websites like Nesterly, help arrange living arrangements between students and the elderly. Many older adults have spare spaces to rent out to students and have a need for a certain amount of companionship, which is critical for their well-being as they age. Each person lives their life independently but share moments of connection and household work, which allows many older adults to age in place: it is a mix between student housing and a retirement community.

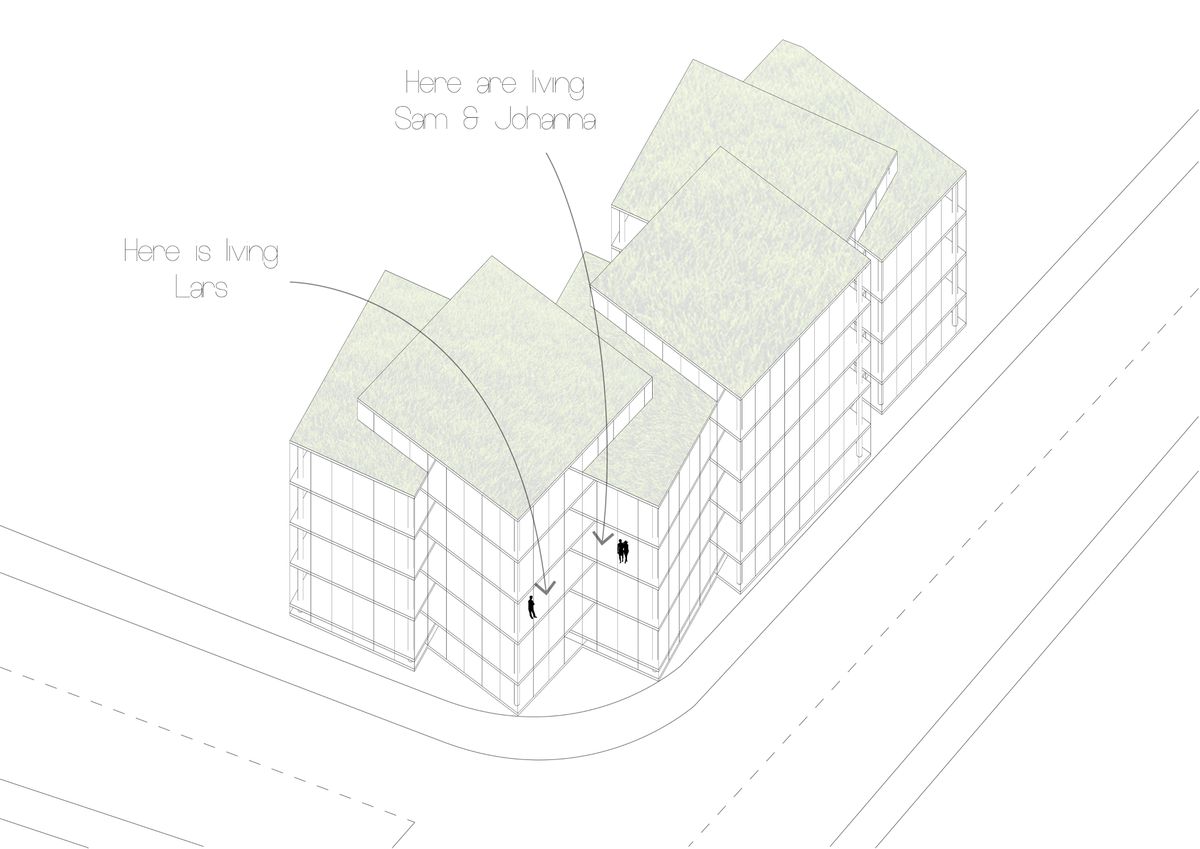

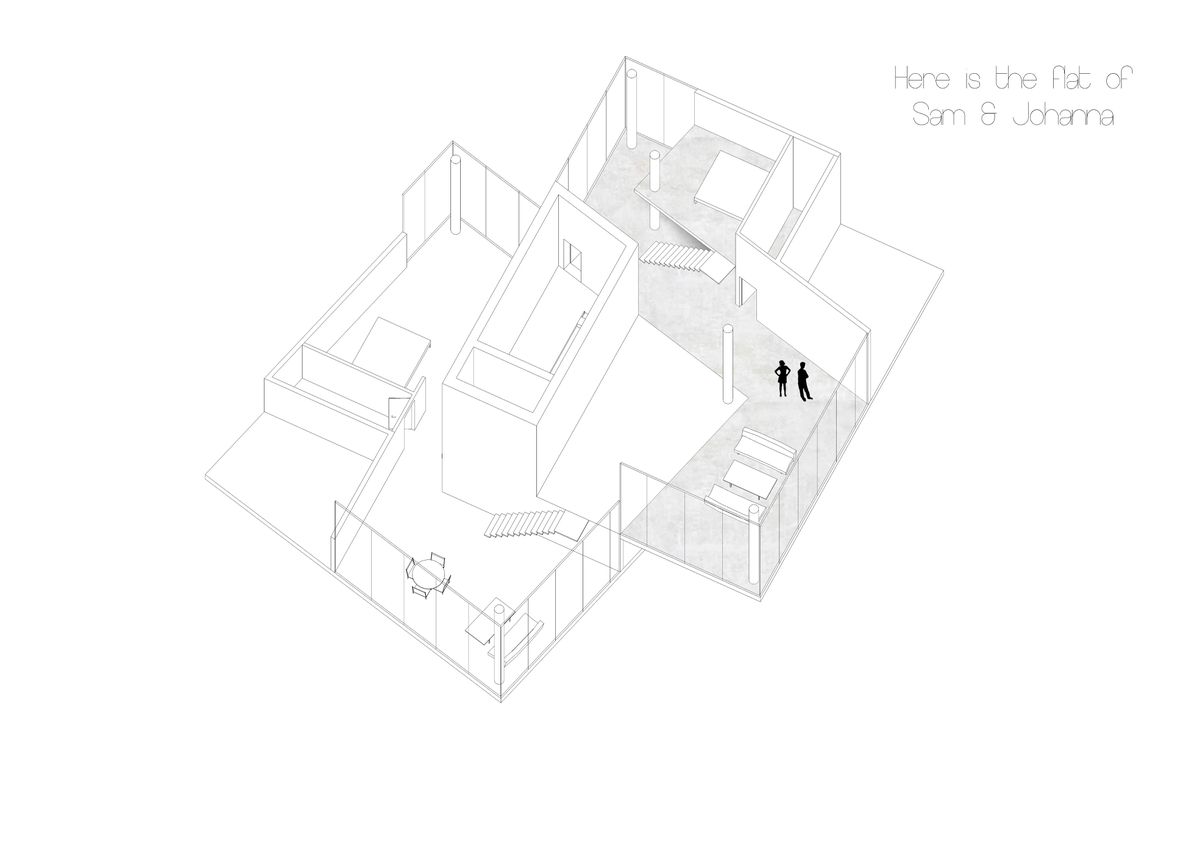

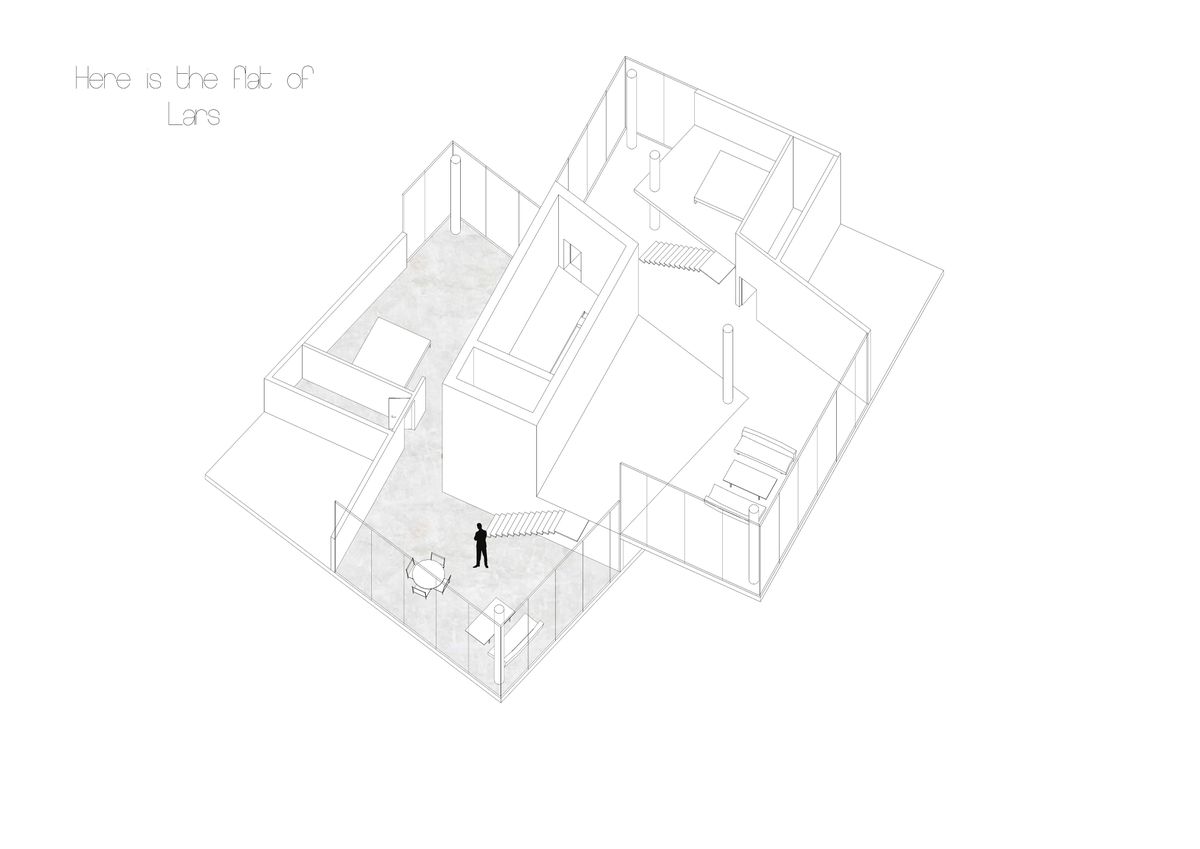

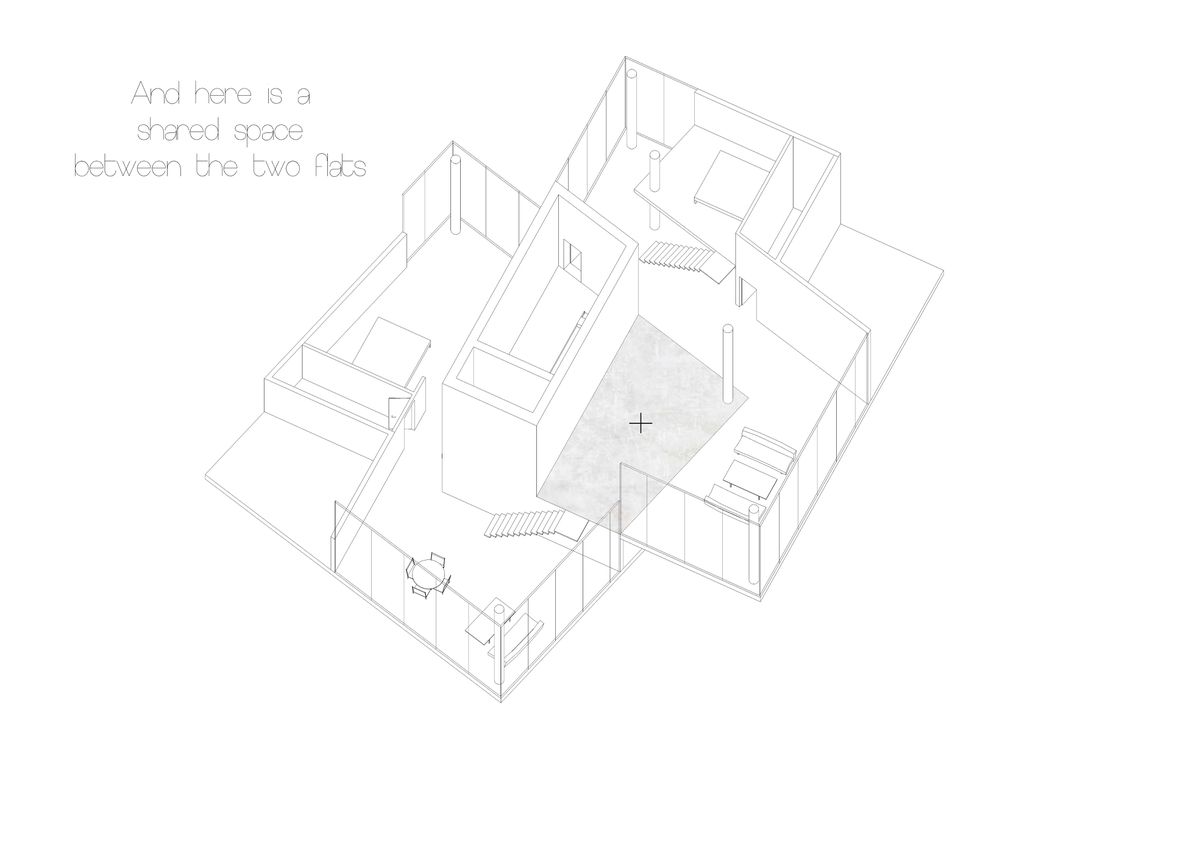

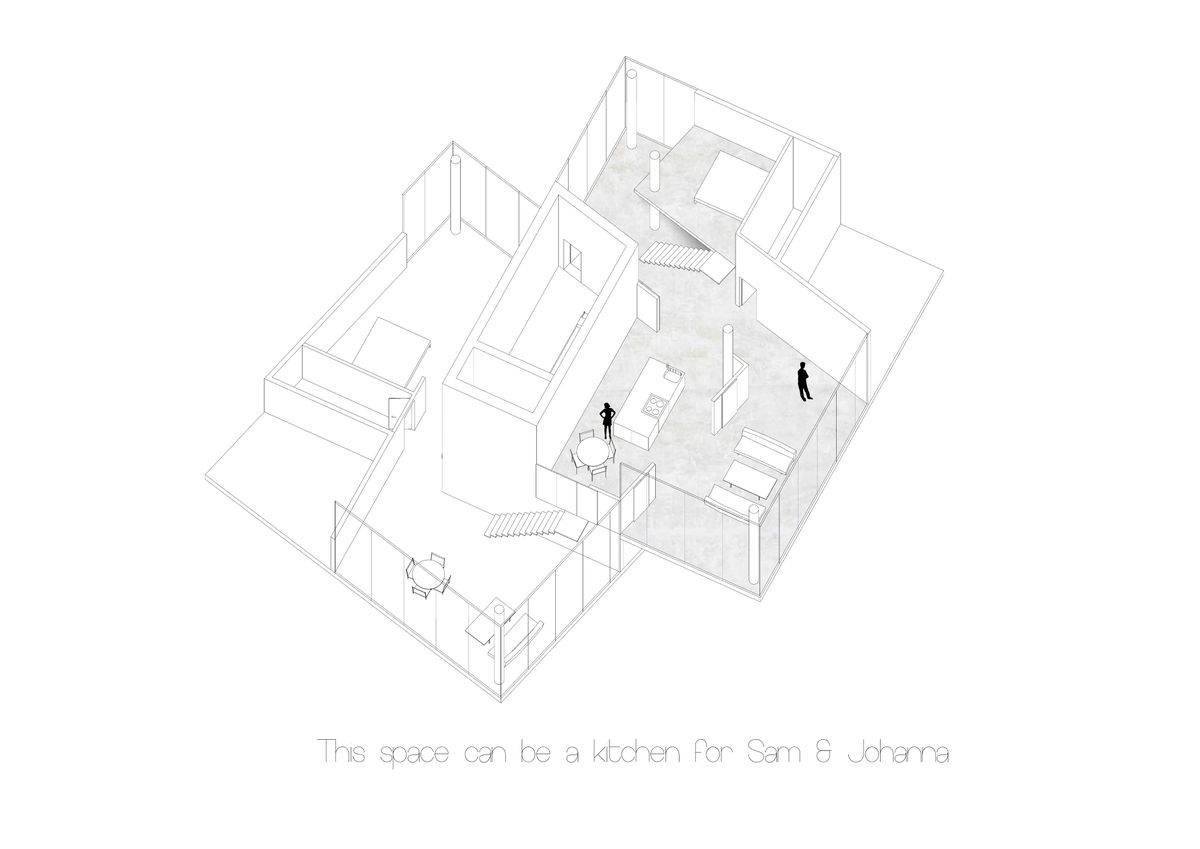

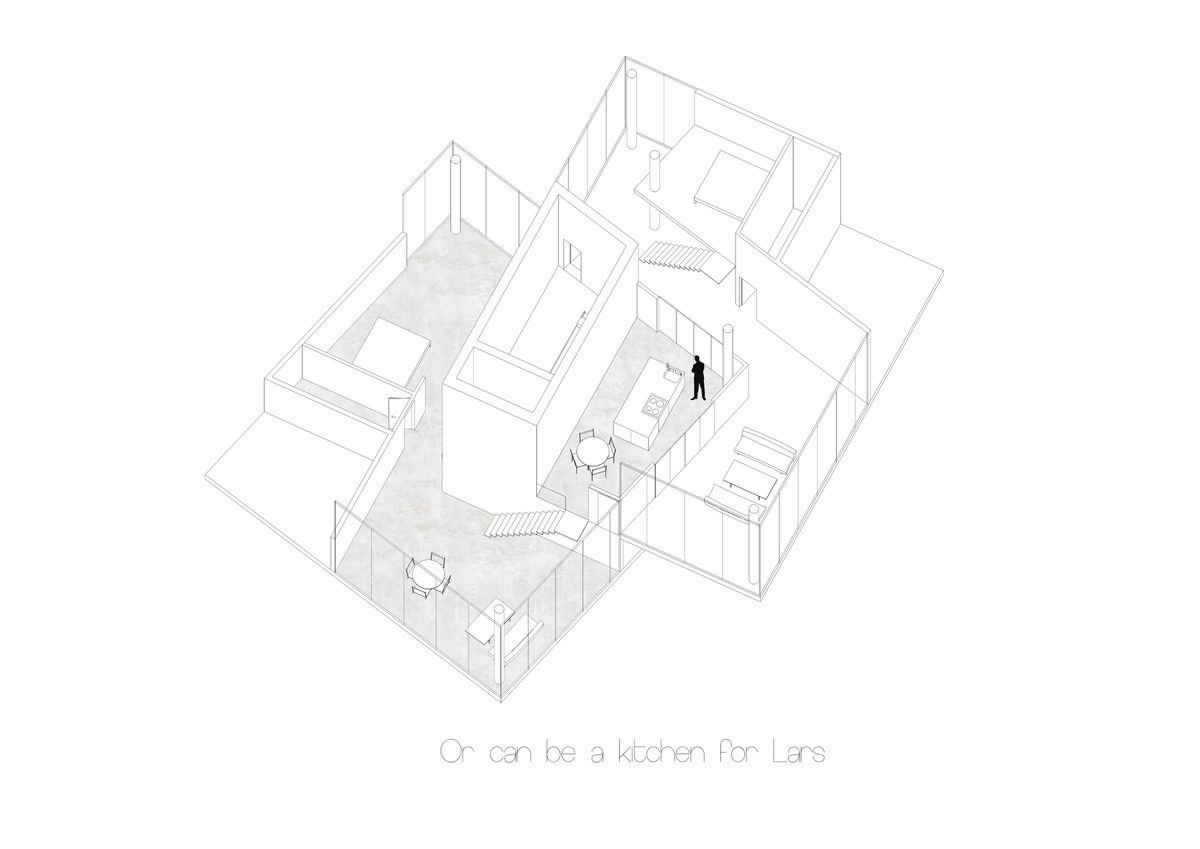

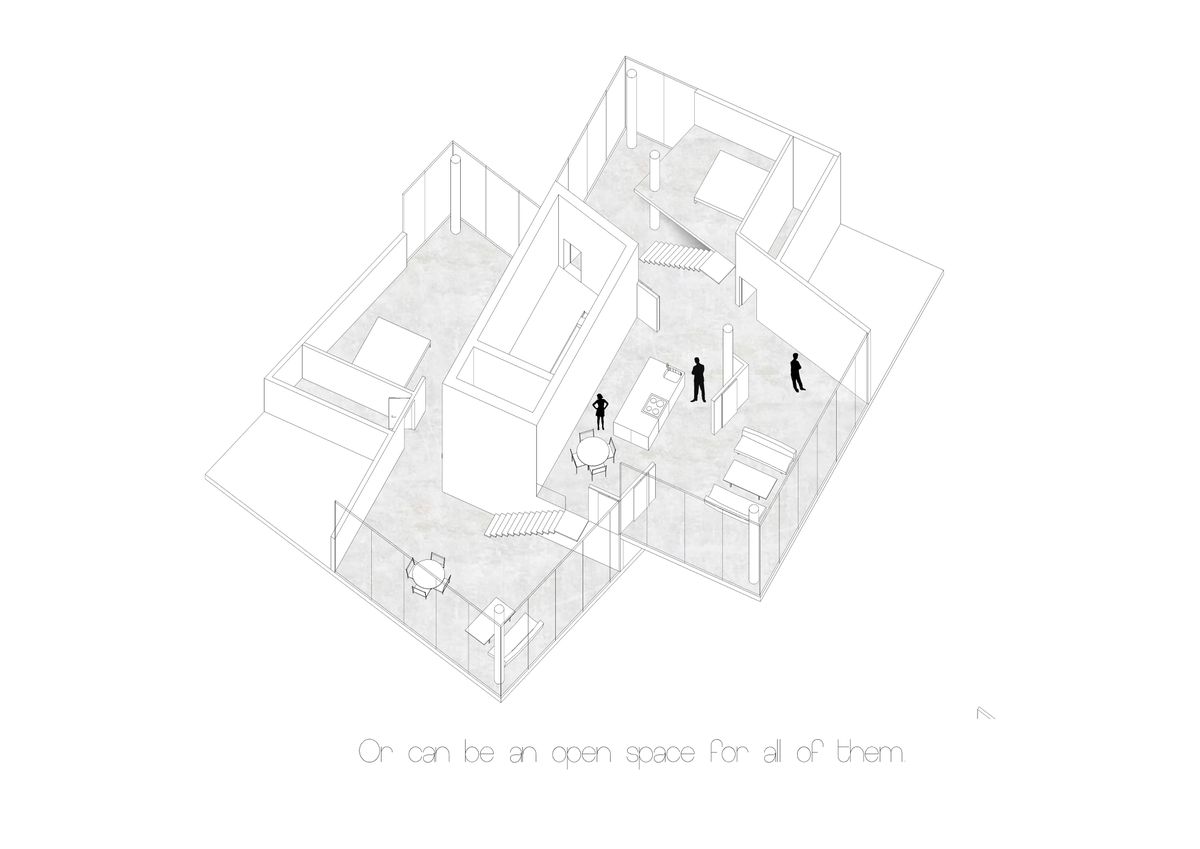

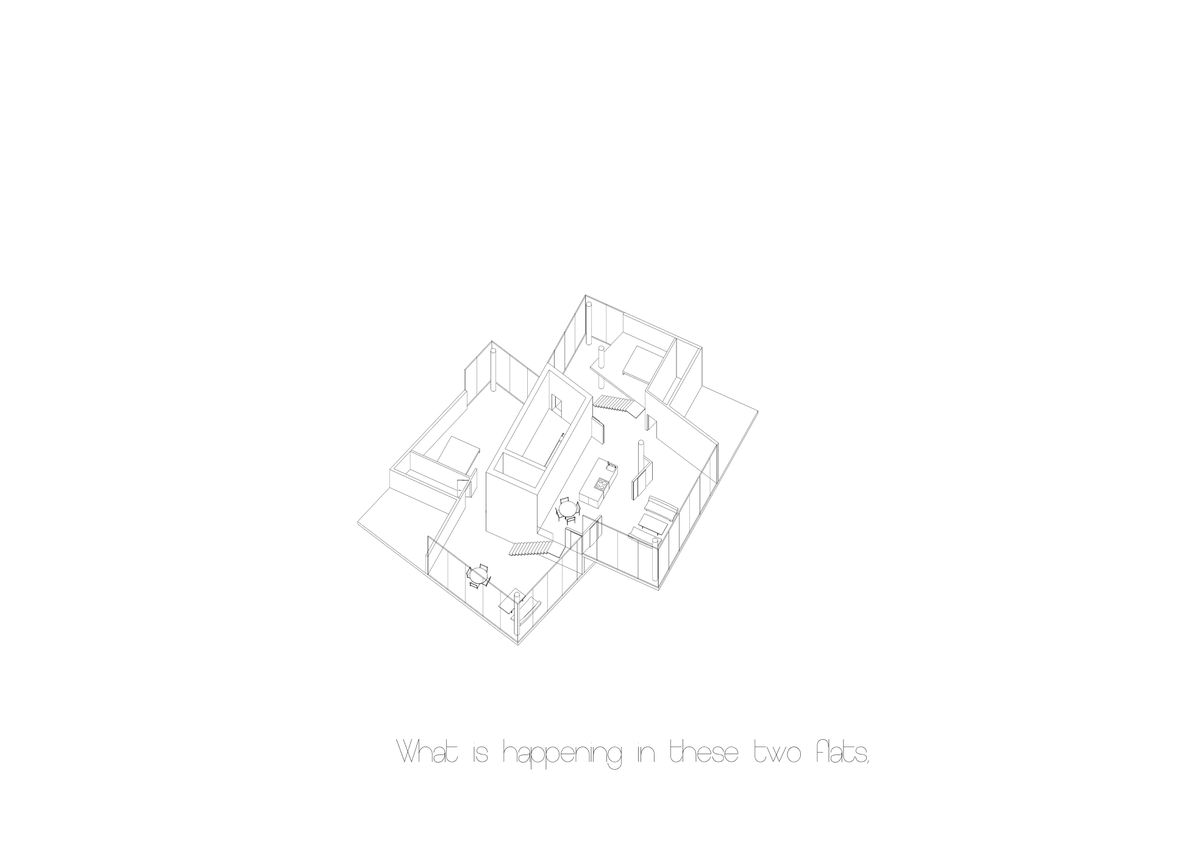

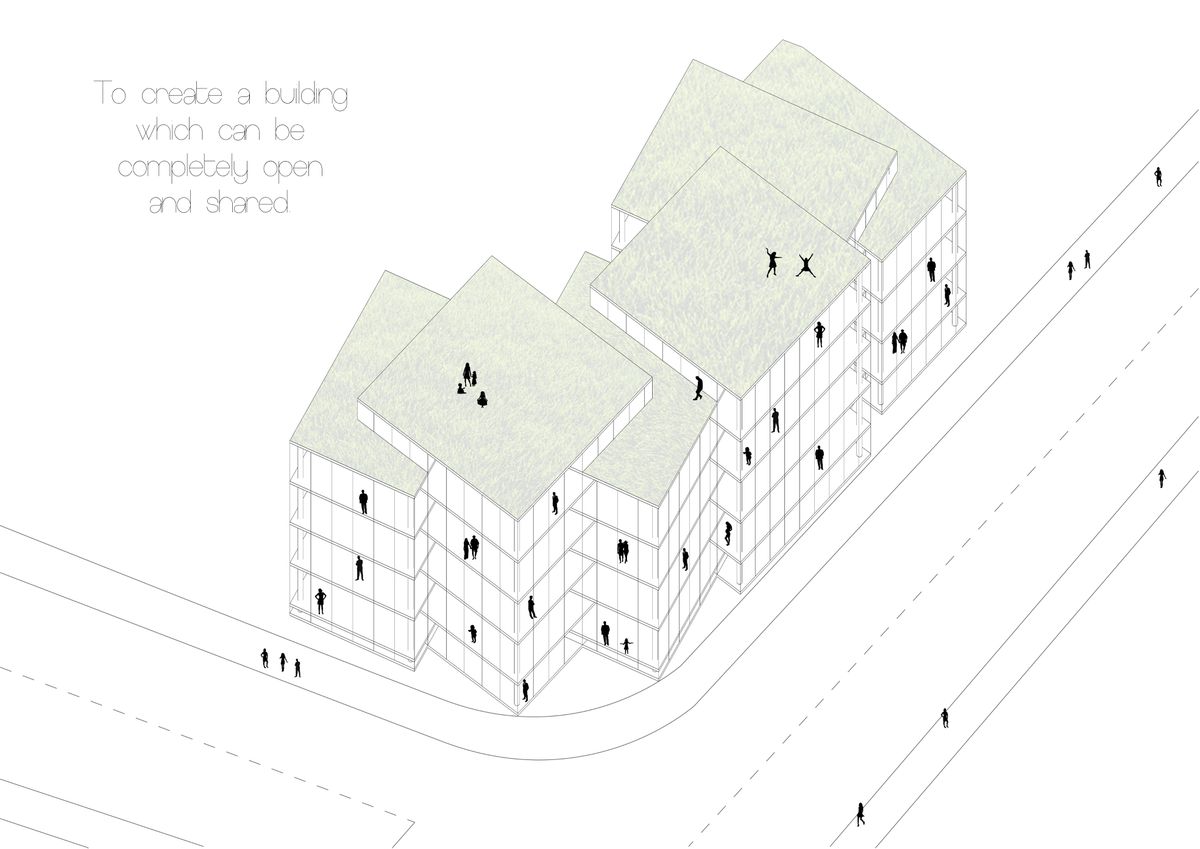

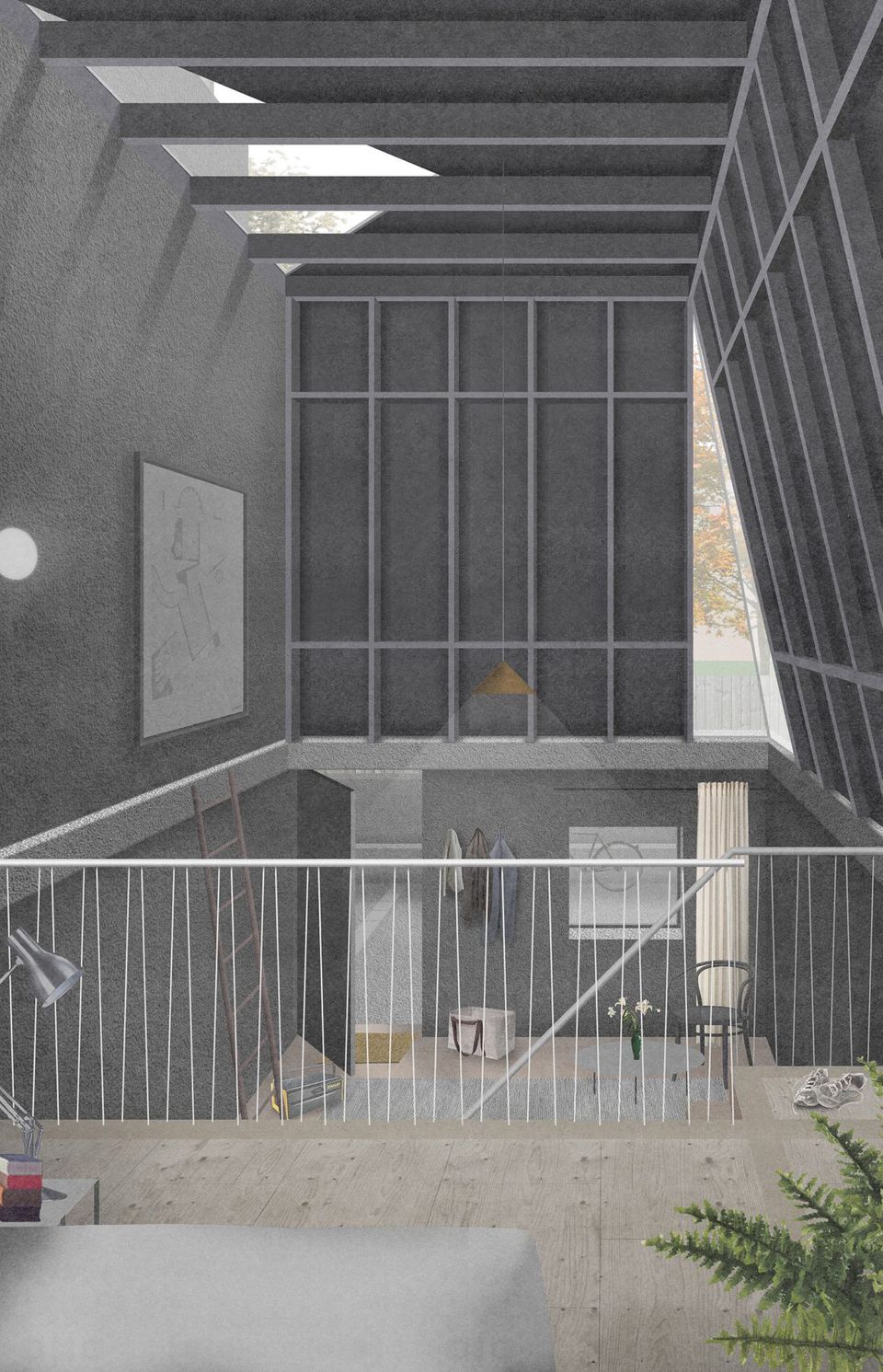

More so, ideas of how to share space have moved towards a formal spatial reconsideration. In a new housing block in Berlin, for example, two units are no longer divided by a wall but a room. The idea of transforming a dividing wall into a volume is an interesting direction versus the notion of a space being structurally flexible—the removal or addition of walls—to accommodate a multi-family unit and co-living. The intermediary space’s use is open to different functions, which is discussed with the inhabitant of the adjoining unit and contingent on their relationship with each other: a communal space of gathering, a space responding to the changing needs of each occupant, or a porous hall between the two units.

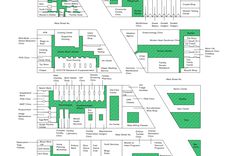

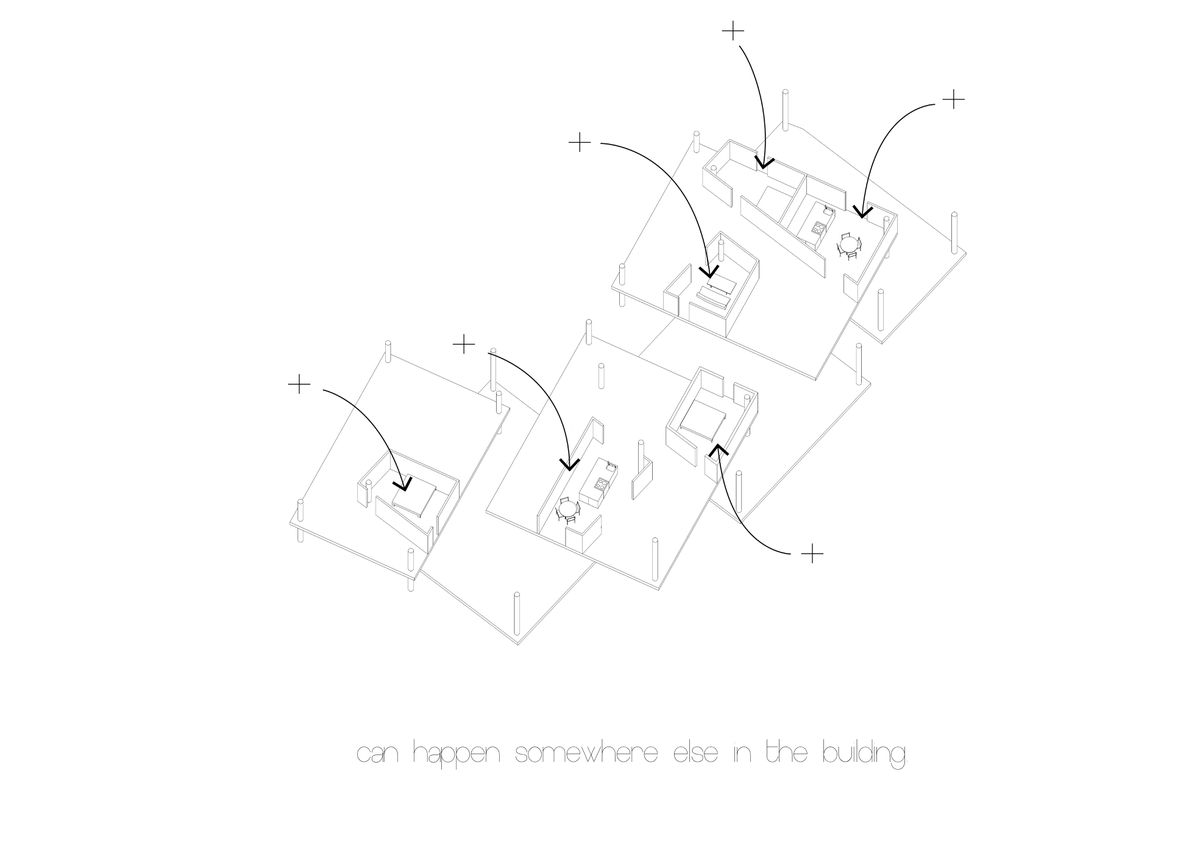

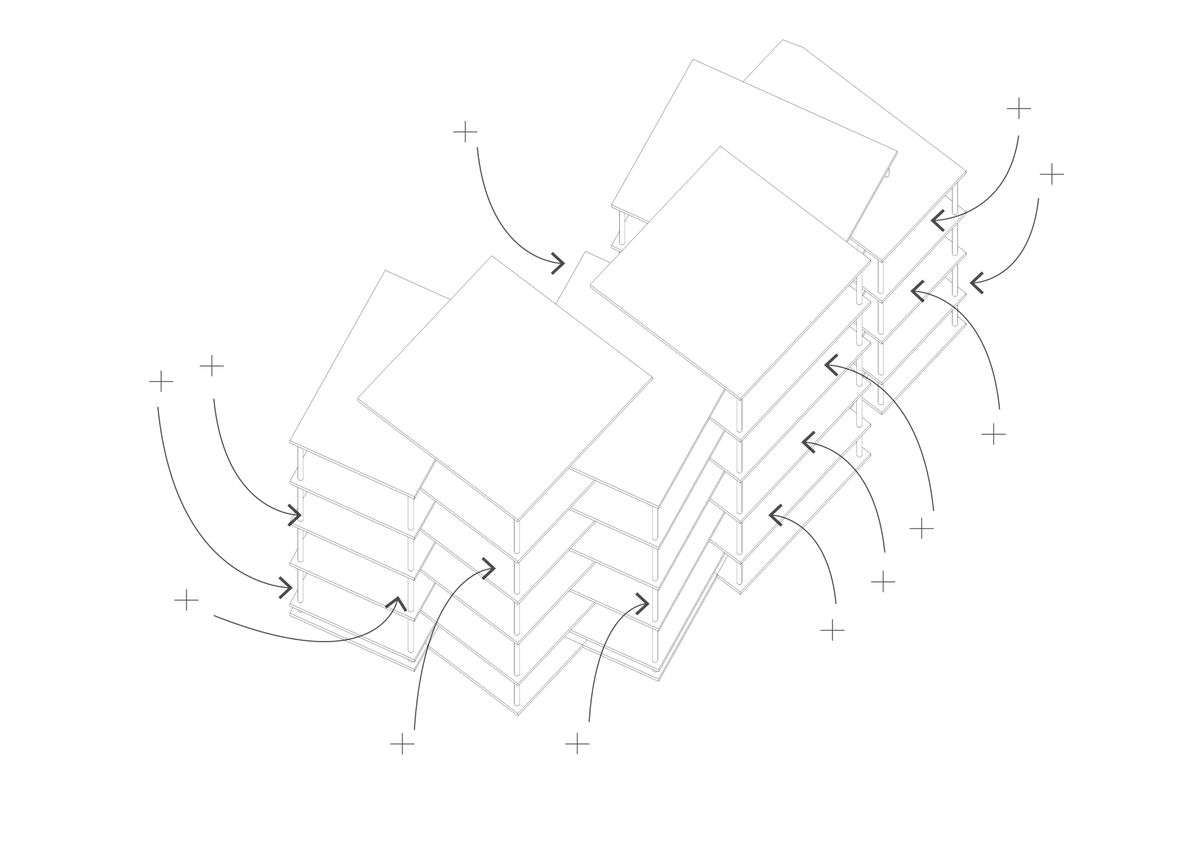

Typical ideas around contemporary living in the city have centred on having less personal space but more shared amenities, whether in the building complex or through the city itself. For his project, Apartment House, Takahashi Ippei divides the house into its fundamental parts, creating eight singleton homes, each defined by a specific function: a house for bathing in, a house for working in, or a house for cooking in? Each resident chooses how they envision spending their time alone at home. The city fills in remaining moments and fulfills all the functions that were removed from the home, encouraging the inhabitant, who live alone, to seek social interactions in the urban sphere.

Age

Growing older tomorrow will be very different than today. The seemingly static phases of life—childhood, adolescence, adulthood, parenthood, retirement, elderhood—have always been subjected to change, but the rate as to which they have changed has accelerated under late capitalism. Often these phases of life are contingent upon certain economic independence, expected family structures, and ideas of one’s societal role attached to one’s age and identity: gender, class, race, sexual identity, etc. It will always start with our birth and end with our death, but how we move through these two poles are evermore put into question. Ultimately, we could see an opportunity to design specifically for these changing life cycles and new phases of life. Once again, how will shifting conceptions around our life’s timeline manifest spatially in architectural and urban terms.

So much of our life is spent at work: attached to work has been an aspect of authority that is accrued through our age and gained expertise, which over the years has come undone. The benchmark of one’s relevance, particularly in the tech industry, has become increasingly younger and for a shorter period. In Tad Friend’s article for the New Yorker, “Why Ageism Never Gets Old,” he observes “this sharp shift in the age of authority derives from increasingly rapid technological change” and undergirding this phenomenon is a belief held by Silicon Valley “that bold ideas are the province of the young.”1 This rapid technological development, paired with the idea that work and business opportunities are connected with your first job or last years as a student, has shifted the perception of when one reaches the peak of their professional career. By the time those working in the digital economy have moved into their thirties, they are perceived as being old: a feeling of obsolescence has crept-in, which is perpetuated by their industry. In response, luxury resorts and retreats, like the Modern Elder Academy located in El Pescadero, Mexico have emerged, aimed at workers in the digital economy who feel that they are no longer able to keep-up in a rapidly changing industry.2 The space and programming of the academy is to provide emotional support and a sense of community, as each share their experiences and encounters with ageism within their respective jobs.3

-

Tad Friend, “Why Ageism Never Gets Old,” New Yorker, November 13, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/20/why-ageism-never-gets-old ↩

-

Nellie Bowles, “A New Luxury Retreat Caters to Elderly Workers in Tech (Ages 30 and Up),” New York Times, March 4, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/04/technology/modern-elder-resort-silicon-valley-ageism.html ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

Concentrating the growth of your career to the early years of your life has reignited an interest in early retirement: F.I.R.E (financial independence, retire early), is a growing movement among millennials where individuals aggressively save, work, and invest to accrue enough wealth to retire in their thirties or forties. Emphasis moves away from generic symbols of material wealth to a greater value seen in one’s time. By working and generating income in a limited timeframe, you free yourself from the obligations of mandatory labour. Ideas of retirement have circled around leisure and relaxation, images of fishing and cruising come to mind, but what will be the home and lifestyle of a new young retiree?

The project Naked House by the architecture office OMMX, is an early example of trying to create a new housing type that provides a financially accessible threshold to home ownership. The model drives cost down by outfitting the home only with only the bare necessities: it has no internal walls, floors, or finishes. Overtime, the well-sized space is slowly added to by the residents, responding to their specific needs at that time and financial circumstances, which helps avoid amassing a crippling amount of debt. Architects may want to start to define and design a new model of home connected to the concept of affordance, in this case a model of incremental spatial specificity.

Subsequently, each generation forms new notions around work, which are reflected in how our workspaces are designed. Gen Z (1997-2012), the first generation of true digital natives, are entering the workforce having grown-up with sharing themselves online: ‘The self’ has become commodified, and for some, the broadcasting of oneself has become a viable form of work where one’s image, relationships, attention, and personality are able to be monetized. As a result, the recent phenomenon of ‘content houses’ or ‘collab houses’ have emerged, where influencers and social media stars live together often in McMansion type homes—usually but not exclusively in Los Angeles—have become new spaces of work and play. The exponential growth and popularity of the new social media platform Tik Tok, has spurred the latest iteration of content houses, the most notable being “Hype House,” where some of the platforms most promising young stars have formed a content creator group. The draw for living together “allows for more teamwork, which means faster growth, and creators can provide emotional support for what can be a grueling career.”1 And even if the settings seem to allude to a constant party house, strict rules tuned to productivity are in place to make sure all do their jobs—produce videos. Home and work have fully coalesced.

-

Taylor Lorenz, “Hype House and the Los Angeles Tiktok Mansion Gold Rush.” New York Times, January 3,2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/03/style/hype-house-los-angeles-tik-tok.html? ↩

Technology and science further contribute to changing parameters of the traditional life cycle, especially as it relates to the body, aging, and fertility. Having a baby or creating a family was normally understood to take place in a specific timeframe in a woman’s life. But new forms of fertility treatments—egg freezing, IVF, egg donation, surrogacy, etc.—paired with woman’s emancipation have challenged those assumptions, giving newly gained flexibility in family planning for those who have access to treatment. In the United States , about one-third of adults have said they required some form of fertility treatment, with millions more around the world.1 While more than eight million babies have been born via IVF since 1978.2 As fertility treatments have become more commonplace, a need for architecture to thoughtfully reconsider the spaces where these procedures take place has emerged. Currently, they exist as independent clinics siloed off, almost attaching a sense of shame or secrecy to the space, but could they become a site for a new social infrastructure as Hilary Sample has imagined:

“The new clinic could be recalibrated to focus on the well being of those needing reproductive assistance. A space we could imagine linking reproductive health to environmental health, clinics that are in neighborhoods of poor health could bring awareness to those within them, children should be allowed in the reproductive clinic, often children are forbidden, yet in poor and less served neighborhoods bringing a child would be an opportunity for additional support and care. The clinic can be the doula for the neighborhood.”3

In the 20th century, body banks were a repository for human fluids—blood, sperm, and breast milk— but biotechnology is increasingly making it possible to procure material aspects of the body like body parts, genes, cell lines and in special circumstances even our faces.4 Over the past century, we have been able to expand the average life expectancy by thirty years.5 Now, biotechnology may offer a way to increase our quality of life in those years, marking these body banks as sites with greater community importance. Could body banks become something more widespread as integrated structures in our urban settings and will they need an architectural interface to engage with the public?

We can extend our lives but eventually death happens. And so just how the rituals around birth are being reconsidered, many are re-designing funerary practices and the rituals surrounding death. Projects have envisioned that one’s body could be liquefied and used to fertilize a memorial garden for the deceased; a new crematorium where the cremation process is witnessed by the family; or to imagine memorial shrines as an integrated piece of urban infrastructure and public amenity, while also becoming a place to publicly grieve.

-

Gretchen Livingston, “A third of U.S. adults say they have used fertility treatments or know someone who has,” Pew Research Center, July 17,2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/17/a-third-of-u-s-adults-say-they-have-used-fertility-treatments-or-know-someone-who-has/ ↩

-

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, “More than 8 million babies born from IVF since the world’s first in 1978: European IVF pregnancy rates now steady at around 36 percent, according to ESHRE monitoring,” ScienceDaily, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/07/180703084127.htm ↩

-

Hilary Sample, interview with author, June 2020 ↩

-

Rebecca J.Rosen, “Banks of Blood and Sperm,” The Atlantic, July 31, 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/07/banks-of-blood-and-sperm/375341/ ↩

-

Adam Gopnik, “Can We Live Longer But Stay Younger,” New Yorker, May 13, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/20/can-we-live-longer-but-stay-younger ↩

Ultimately, the question being posed is does architecture enter into dialogue with our new and diversifying spatial needs, with a renewed design ambition in supporting society? Architecture can be a tool for change, but it cannot anticipate the needs of the future by copying its past. Thus, architecture should actively listen for the pulses of societal transformation to better support, encourage, and carefully frame each moment of life.

This article is part of the Catching Up With Life project.