A Space for a Blended Family

Sam Jacob reflects on the role of the home. Photographs by Aubrey Wade.

What comes first: the home or the family? Does the home serve our idea of the family? Or is our idea of family simply a function of the way in which homes are designed and built?

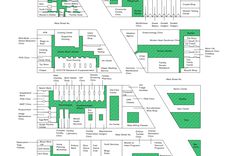

The design of the stereotypical family home is most often derived from a generic template driven by market interests. It makes many assumptions about the nature of the “family” that it might contain. Living rooms, kitchens, smaller bedrooms, and a single master bedroom—a name that is in and of itself enough to forewarn us that its idea of family is a very particular one, one that reinforces a patriarchal structure by means of the language of real estate listings. The formula that is used to create this kind of home is shared and transmitted like meme, as if it were a naturally occurring fact of life. Those involved in large-scale housebuilding—including architects—act as if they have little agency in its authorship and as though they are instead obliged to ritualistically recite its logics. They behave as if “architecture” is simply the physical container for a fixed idea of family, rather than recognizing that the real design project is the family itself.

The typical family home arranges a set of spaces as a series of thresholds: the spaces with more public functions are usually found on the ground floor and the more private ones are found upstairs, where the bedrooms are arranged such that the master bedroom has the most privacy of all—possibly with an en suite bathroom of its own. This quasi-ceremonial sequence positions the marital bed as a sacred space, offspring as being overseen within its own cells, and the ground level as a semi-public agora that mediates between the family and the street beyond.

The subtext of the family home can be read in its particular arrangements of sex, love, and power—arrangements that are often motivated by shame and control. This is made clear by how frequently the design of the home is employed as a moralizing device, imposed from above to “improve” the behaviours of its inhabitants.

This generic solution, first developed in the West as a derivation of historical forms of living arrangements and codified at various historical moments (including but not only in Georgian and Victorian homes, early twentieth-century suburbs, postwar developments, and mass-housing projects built from the 1980s onwards), has become a global template, exported first through colonial forces and later through the hegemony of global banking. In other words, this typical house has its own family tree, and its branching off often coincides with societal changes: the rise of a middle class, technological innovation, the introduction of social welfare, and models of development economics, for instance. But just because the form has a lineage does not necessarily mean that it is in any way functional. The home (in this generic form) imposes its bastardized and ideological pattern onto the reality of what a family might actually be—part of the solution might even involve putting the generic home on a couch and asking it about its mother.

The generic home’s idea of the family is singular, more specifically, it’s nuclear: the model of a Western married heterosexual couple with two kids. The possibility of a family is, however, far more diverse and fluid than this retrograde model. It may or may not include a couple, a thrupple, or a single parent; it may or may not include children, the number of whom may or may not remain constant from day to day; it may or may not include the parents of parents or the children of children for reasons of culture or care.

If we were to frame the question of the home as an architectural one (rather than say, an economic one, which is of course related to the notion of the home as often being conceived of as a financial instrument rather than a spatial or functional entity), and if we were to frame the question optimistically, i.e. operating under the assumption that the generic model of the home can escape its own orbit, then, perhaps, answering the question of the home would require an understanding of the spatiality of the family itself. How can a home manage all of the intimate thresholds between bodies, love and sex, care, and togetherness and apartness? How can the fixed material of architecture accommodate change over time, whether changes occur day to day or over the course of lifetimes? Custody arrangements, hookups, breakups, ageing, and other familial narratives require accommodations that allow them to unfold within the framework of the home.

What might domestic thresholds look like if they negotiated a wider spectrum of relationships and conditions? While working through this question may mean breaking apart the fixed notions of domestic spatial units of halls, corridors, and bedrooms, the abolition of spatial difference in, say, the conception of the open plan can reliably resolve these issues. Following this abolition, we will have to engage with questions of bodies and civility, as well as the many possibilities of sex—possibilities that may or may not include long-term partners, naked strangers, and teenage experimentation. Sex may indeed prove to be the ultimate problem of the family home.

We cannot assume that the history and culture of the home is irrelevant. After all, there are many models of domesticity that precede this generic home that might prove useful (or at least suggestive) in rethinking it—even those that this current model has borrowed from directly. History can be radically inspiring, even if only because it reveals other worlds that are (or were once) possible.1

The home is architecture in its most revealed form, exposed as a project at the fault line between intimacy, fantasy, dreams, and fear on the one side and collectivity, society, and politics on the other. Resolving the question of the contemporary home should first require understanding the spatiality of the modern family and its various component bodies in space and their shifting roles and relationships over time. Architecture’s role in making the spaces of contemporary domesticity might also mean confronting its own house. That is to say, we must recognize that architecture is not a neutral, benign, or objective problem-solving activity. Architecture is a product of the same history that produced the typical family home in question. Perhaps any attempt to design a home for contemporary domesticity should first interrogate its own internal organization of issues of power, gender, and sex before it sets out any plans for the home.

-

Note here, for example that even something as fundamentally and apparently self-evident as the bedroom is a relatively modern invention. ↩

This text was written by Sam Jacob for our publication A Section of Now. It is published here as part of our Catching Up With Life project.