New Society

Giovanna Borasi and Sam Chermayeff introduce our exhibition A Section of Now

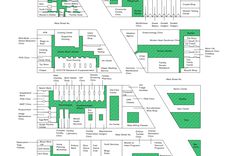

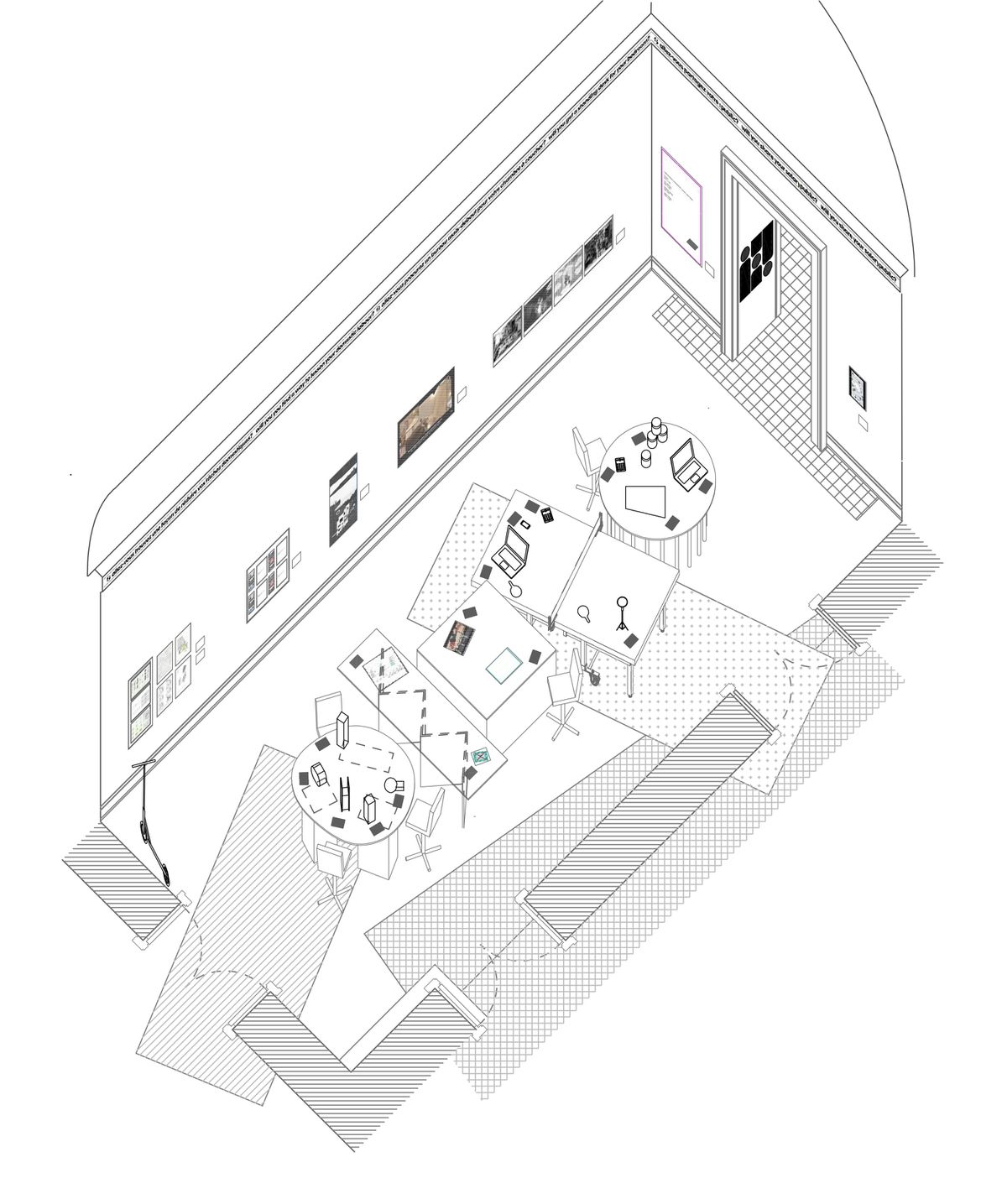

A Section of Now: Social Norms and Rituals as Sites for Architectural Intervention was curated by Giovanna Borasi, with exhibition design by Sam Chermayeff Office. The exhibition opens in our Main Galleries on Saturday, 13 November, and runs until spring 2022.

- GB

- My main interest with A Section of Now is really looking at the relationship between architecture and society—how one can feed the other, or relate to the other, or mirror it, or how we can look at society and then say, “That’s the architecture that we need.” The gap between what society needs and what architecture is providing is becoming bigger in certain cases, but there may also be opportunities for intervention that we, as architects, are not jumping into. I wanted to hear what your thoughts on this kind of relationship are, and if the relationship has changed or has always been this way?

- SC

- Yeah, it’s changing. And I absolutely care about the questions that you’re asking with A Section of Now beyond my own work, and just as a member of society. I think that your conception of the show is humanism beyond architecture, in a sense. I think that there is oftentimes a wide gap between what society needs and what architecture is providing. You’re talking all the time about how we deal with the notion of “self” in architecture, but in the show that also applies in quite a few things that aren’t architecture to their credit. It seems like the place that you’re starting is this human-scale intervention that might influence architecture. I appreciate that you never say that explicitly, but somehow the observations in the show are saying to architects and to other people that you can fill this gap with a new understanding of how we relate on a very individual level, despite the fact that it’s a communal answer.

It’s also interesting to think about an individual working in a communal. The show is trying very hard to do that, and I think good architecture now is also trying to do that. It’s somehow as much as anything about boundaries and particularities within community, meaning that you can have a real diversity of people. We’re in this moment where we have to decide in a really active way to bring diversity into high culture… we have to do more work on reflecting diversity. And diversity could be anything; it doesn’t have to be about race, gender, or whatever, as opposed to trying to group likeness together. The show is about that difference, I think.

- GB

- I think it’s a nice way of reading the work that we have done. In the first gallery, we’re asking what defines family, what is friendship, what is love, and so on, but really in a way where these things are based also on individual choice. I think the objects that we show and the photos that we have selected with curator Melissa Harris all try to do what we’re saying: not reconcile a society that has to be one way, but where all this diversity is possible, and can find a relation in space.

- SC

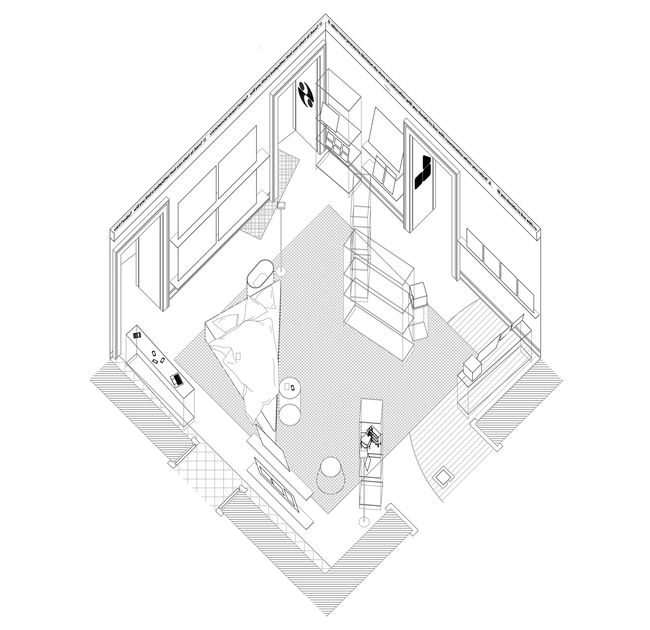

- The old title of our Triangular Bed which is in that room, for the nuclear family and its opposite together, is about that. You can project onto it a lot of different moods. I hope that this ability in architecture, furniture, even down to the smallest little thing, invites people to feel connected and very much themselves. Other galleries are more explicitly about the self. There’s one where you talk about the “cult of self,” and you’re doing a really good job of not judging the cult of the self. But it’s hard, because sometimes it feels like, well, maybe you shouldn’t look entirely at yourself all the time.

- SC

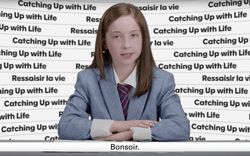

- Let’s talk about the TV stills that are displayed in the beginning of the show and what that means in terms of society, because by default you’re showing things that are essentially historical, even if they’re pretty new. How do you imagine that someone coming and starting this show there might ground themselves in the question?

- GB

- At the beginning of the research was a very intuitive idea that we tend to experience changes in society through TV programs. And because of global distribution, these are becoming globally shared things. Take what is happening now with Squid Game, for example: it’s a Korean program, and all the world is looking at it at the same time. I think it is interesting that through the power of the distributor, it is becoming a strange shared experience that any person, any culture can read differently, but suddenly everybody is reflecting on those societal issues or those societal changes and so on. I always thought this was fascinating as a phenomenon. I remember seeing Friends, and this idea of friends living in facing apartments and meeting on that sofa all the time was something that we didn’t have when I was growing up in Italy. You project the idea of society through this. I found that it is really a particular moment where these experiences are lived simultaneously.

These TV series we selected are understanding or anticipating society maybe much more than architecture is nowadays. Where we have seen in TV series all these shifts—the presence of surrogates, the impact of technology, family changes, you name it—all these things have been discussed, and somehow there is not yet a space for them. I thought it was interesting as a friendly way of entering; maybe asking a visitor “what is society” seems like a big question, or “what is the society you will want?” Coming into the show and seeing images from TV that you also know, you start to read that sort of normality. - SC

- Right. It’s like the German edition of The Communist Manifesto starts with this sentence which I can’t say in German, but in translation is essentially “this story is your story.” I suppose the television starting point says that, and then I guess it also says this is a collective experience that we all understand, so you understand it too. You’re also isolated and by yourself in that way, so you need to consider that problem. I think people will understand that at some point. The show is going to go back and forth where you feel like, “Oh, this is just like my life,” and you’re going to think, “Oh, this is not my life,” and then you’ll get some kind of answer about it. It’s quite an institution. It’s quite an ambitious thing to try to do.

- SC

- This question of diversity that you keep open is also very nice. I somehow have to be more direct about it in my work as an architect, not because I think I should, but because I’m afraid of the subtlety. As an architect, you constantly have to fight aggressively for something. You have to say, “No. You can’t do that the boring way. You have to do this the other way. I promise it’s going to change something.” You’re constantly having to define a position. It’s the annoying part of our profession, but it’s very hard when you’re talking to clients to convince anybody about ambiguity.

But I also like the ambiguity, because several times we’ve been on the phone in this long, long process of creating the show when I’ve thought, “Why don’t I just say this is good and this is bad?” I like this process with you and the show that you can recognize that ambiguity and say, “It’s both really good and really bad.” I don’t know how we do that as architects. - GB

- It’s true, and I think the show will demonstrate that intention that we had from the beginning to really place the visitor in this ambiguity of a changing society: now people live in this way, but where do I situate myself? Do I embrace this, do I like it, am I scared? From the beginning in conversations with you was the idea of the visitor coming in and positioning themself as a self, as a single person, but also always being placed in a condition of sharing that is very characteristic of our current context. I think there are a lot of subtle things that are happening that you were able to achieve with that kind of ambiguity.

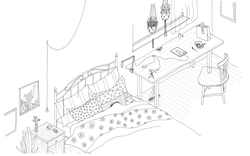

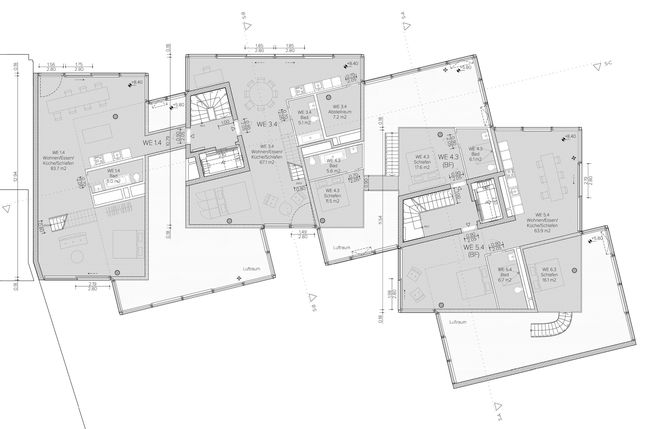

If I think about the other projects of yours besides the Triangular Bed that are in the show, both Kurfürstenstraße in Berlin and the Anthropocence LLC project in The Rockaways, I think you achieve that sort of ambiguity in terms of ownership or territory. With Anthropocene LLC, your bedroom is almost like a motel. It’s yours, but it’s also identical to others, so there is that notion of equity. And then there is a space that you share with others, and it will be up to you as an inhabitant to decide how you share that space. With Kurfürstenstraße, there is a room that defines the space in between one apartment and the other, and the ambiguity of living separately and living together will collapse. I think you are achieving, with those projects, that ambiguity.

- SC

- Thanks for saying so. I think the whole show and my work in general are almost exactly the same in terms of their ambition in the broader sense because, when possible, it’s so magical to get to a humanist level. Going back to this idea of new society, there’s something about now that is just recognizing that, after decades of modernism, we really love that element of the human. I do also love the modernist intention to be universal; I love the idea that we’re all the same… or at least I did. I certainly grew up in that logic. Now, it’s actually realizing that we all have this special story. And that strikes me as a very particular change that is, as you said, also scary. In the show we’re asking visitors to decide something about themselves which is—if you put it in a dark light—a bit aggressive, but also the fact of having to do that work is interesting, in that modernism explicitly said you didn’t have to do it.

Now, we’re in this special moment. In our office, we’ve started making very specific kinds of furniture pieces, for example, that are to put your makeup on that don’t make sense for everybody. In another project, we’re trying to turn toilets into acoustic environments for phone calls and other oddball things. And these become not universal. Would you say that that’s the crux of the change in terms of what new society means, what’s new? - GB

- I think it is. It is this idea of a very different form of universalism that is actually created more with this kind of mosaic or puzzle of things, and so that is the change really.

- SC

- Alright. And then, we had to figure out within that how to make architecture that responds to that need, because the reason that there’s a gap is not just modernism’s fault. It’s also just notions of efficiency, let’s say non-specialness. We have to figure out how to invite people to make their own situations.

- GB

- One of the passages I really enjoy in the show is from the gallery where we show all these combinations of living based on variations of new families—focusing on very real needs like hugging, to having a doll as a human scale companion in the house with you—into the next gallery where it’s still about housing, but somehow not starting from this personalized and humanistic approach, and instead looking at big questions of housing, affordability, and equity understood in economic terms. For me, that is one of the most striking passages, where you are still speaking about the same thing, but completely from another position. I think another thing that is of the now is the fact that it’s not just one right answer in the approach to architecture.

- SC

- The question is how we as architects can make a framework for those two strategies, because they are not mutually exclusive. When we talk about equity as community or collective in some way, it is also about recognizing the problem of individualism and therefore the need for a collective response to this individualism. In that light, the whole show works together, but particularly those two rooms. I’m not sure that the architecture in those rooms isn’t also as much about “collective” as an architectural expression as it is as an equity expression.

The thing that holds it together is very clear in terms of the fact that we need a doll to hug. We can look at that without judgment, but we can also say that people aren’t able to hug enough in real life. Both of those things can be true, and therefore we need to actually also be together. That’s a complicated set of steps, but it’s true. You can recognize that we need to be different, and then that that difference is also driving us apart, and then we need to be together again, which I think architecture can take in. In its best form, it does all of those things.

I think that the only way to actually make togetherness is to think about equity differently, even if some of my projects aren’t as explicit about that aspect as others. And certainly once you start making great things, they start to become luxurious, and so it goes. I don’t know how to fix that. It’s such a sad thing that architecture is separated from humanity by virtue of its commodity. It’s so hard not to think about architecture just as money. There’s a willingness to understand that it has to be human and not financial. - GB

- It seems to me that the exhibition was a way of calling to architects to think, “How do you position yourself in this? Do you see that you can do more, that you can look at this and orient yourself or say I don’t care? But if you care, what are you doing?” More and more, I see that this activist part is not only directed to the architect or architecture as a discipline, but even more to regular citizens: the visitor will also need to ask themself these questions.

- GB

- The show closes with the gallery we designed around the idea that one of the things that as humans we have really started to play with or to design is our life cycle. We are able to prolong our life, we are able to prolong our time as parents, we are even able to retire much earlier in life. Somehow, it’s also challenging the modernist idea that was reflected in the city, where you sleep, you work, you move. Somehow now this is really going beyond that. We had years of this kind of hybridity, where architecture was really playing with the idea of hybrid form or hybrid function and so on. Now, I think we are even reaching another level where, because of the fluidity of these phases, a job is no longer a job, and a home is no longer a home, and all these kinds of things. I was pleased at this in the last gallery because it provides some content, but it also leaves very open to interpretation the question of what will be the next level or the next commitment or the next work of architecture. If you really take this society seriously, what is the kind of architecture it will generate and desire?

- SC

- Well, I think that the last room is the most difficult on the viewer in the way that we’ve been talking about it, because you have to form a position. You have to be like, “Is that good? Do I want that?” It’s not clear to anyone, “Do I really want to live longer? Do I really want to be alone?” Of course, you can walk through and just think, “This is weird,” and go out and have a drink and not deal with it, which is fair enough. The fluidity then just requires more agency and self-authorship. That’s very frightening. I think that that’s in fact the scariest part, that you have to decide about those questions.

And then, that leaves us so alone. There’s something about the clarity of modernist live, work, play, eat, sleep, do it again that’s so clear that inherently it’s communal, because it’s universal. If we have to decide what work is, a cycle of a day, of a life, of a month, of a week, if suddenly we call that a choice, then we’re really left alone. This show, and the last room in particular, is really calling attention to how much choice we have now. We can see the trajectory of that continued freedom, and all the things that enable that freedom are going to become less expensive, and there’s going to be more and more equity in that choice.

I guess that freedom that I have now, let’s say privilege that I have, is also making me personally want to address this collective on an almost selfish level as well. Architects have to face that, because architects are inherently privileged people on the whole. It’s just by its nature a privileged profession, and we have to recognize the pitfalls of that privilege. That’s especially true now in terms of any number of movements from the last year, ranging from the political crisis in America to Black Lives Matter to many other things. That freedom and also that division can be really isolating and siloing. Partisanship also makes one want to go toward community.

In my projects, I have to give a tremendous amount of credit to people also being weird and asking for something strange. It’s not just that I convince them; they also add their own logic. What I’m really saying is that we have to be better consumers of cities and architecture. Just in this conversation, I’m developing high hopes about it. Maybe it’s actually less frightening than we originally stated earlier in this conversation, this notion that people are going to have to form a position themselves. Maybe new society is about people’s ability to form that position.