A Roof Can Be Anywhere

Text by Fabrizio Gallanti

Getting to Shoei Yoh is difficult. First there is the long haul over Canada and the Pacific Ocean to Narita, Tokyo’s international airport. At Narita, one emerges into the glitzy international arrivals lobby only to shift to a smaller, domestic and 1970s-ish terminal, where one can grab a bowl of curried rice while waiting for a flight. It is another two hours to get to Fukuoka, over the islands and rugged coastline of Western Japan. Finally some rest, in the hotel Il Palazzo, a fine building by Aldo Rossi, which looks out on to Nakasu island notorious for its red light joints and informal hawker restaurants. But the trip is not over. It is one hour by train from the main station of Fukuoka in Hakata, named after the merchant area that has been for centuries the core of the trade with Korea and China, to the town of Maebaru. From there a taxi crosses an idyllic rural landscape dotted with small farms, carefully manufactured retaining walls that control the water of the rice fields, and hills covered by a thick layer of dark green trees and bushes. The taxi climbs over one of these and all of a sudden, at the other side of a cliff, the luscious tropical vegetation plunges into the roaring Pacific.

An ethereal, almost perfectly transparent volume floats over the slope. It is a house, called by its designer “Another Glass House” - a cantilevered platform sustained by two oblique cables, attached to two concrete pillars, that seems to levitate. Inside, the unobstructed view over the landscape is enhanced by a slightly blue filter applied to the glass panels that surround a spacious living room. Nature becomes an abstract element within an austere and elegant modernist frame. It is inside this house, designed as a holiday retreat for his family, that we first encounter Shoei Yoh. He hugs Greg, whom he has not seen in ages. Yoh is slim and short. His eyes sparkle with enthusiasm. It is hard to guess his age; his slightly greyish air indicates that he is in his 60s, but his dynamism makes him look younger.

Read more

Shoei has arranged a few magazines and cut-ups of his work on a glass coffee table: the selection highlighting the elegant roof structures that Greg Lynn wants to include in the Archaeology of the Digital exhibition and the CCA Collection. A cameraman is there to record an interview. Greg and Shoei knew each other from a design studio at Columbia University and it is nice to see them meet after almost twenty years. Over the kitchen counter we drink a lightly sweetened sparkling water, just one of those mysterious products marketed only in Japan. The conversation runs smoothly, the shift towards a more formal interview almost imperceptible. Greg asks him about his approach to architecture: about his grounding in economics and his practical introduction to computers by working with a technology for making spaceframes with licensed from the German company MERO; about his theoretic understanding of computing.

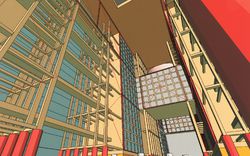

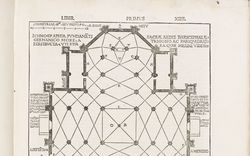

I ask him specifically about Toyama Galaxy gymnasium project (which was built) and for the Odawara gymnasium (which was not); these are the projects that we are most interested in. In both cases, the plan drives the height of the roof – because of the proportion of the room, and also the span, which changes it. The roof is derived from that plan. Shoei says: “Gravity is very selfish to need to go straight down somewhere, to be anchored. But we want to have a roof regardless of where we have columns.” He gestures to the building around us. “For this house we have suspension rods, so a roof can be anywhere; it can be as wide as you want.” He begins to consider the difference between Japanese and European architectural culture. “I was inspired by the New National Gallery in Berlin, which has got columns except on the four corners of the square roof. The cantilever is also my favourite vocabulary. It gives us uplift. If we have a cantilever with a thick shadow, it feels heavy. But as long it’s lit, it feels light and we forget about gravity at the moment we see it.”

He is also clearly a man who values his own individuality. Despite his admiration of Frei Otto and Dr. Paul MacCready, who won the first Kremer Prize with his man-powered airplane; despite his desire to gain the respect of his peers, he is someone who above all values his qualities as an individual. “I have been keeping distance from my predecessors,” he says. “That’s the only way to be myself. As long as I create something, it should be unique to me.” Outside the wind moves the clouds, the trees and the waves. Greg gives me a worried glance: where is the stuff? We came hoping to find some material for the projects that we were discussing, but there is nothing in sight. Certainly, it is a great architectural experience to be there, and the sushi lunch later in the harbour of a small fishermen village is close to perfection, but we start to worry that our trip is akin to a treasure hunt novel. We travel back to Fukuoka. We stay silent. We are jet-lagged and too nervous.

The next day, Shoei comes to pick us up at the hotel. That was not in the original plans. He is cheerful and wants to show us some of his designs, scattered throughout Fukuoka. The day before he drove us to visit a dentist clinic, a sort of UFO-like object which landed over a grassy hill and is still in pristine shape. Today, Shoei brings us to visit a small extension of a maternity clinic. It is an elegant steel box cantilevered over a parking lot, using a straightforward structure of corrugated steel. The interior is defined by a series of coloured glass panels that create an almost otherworldly and soothing lobby. Shoei masters light, material, proportions with incredible elegance and economy. In the city downtown we see his metro stations, where the steel beams seem to defy gravity, holding tiny glass boxes which mark the access within the congested cityscape. Then he drives us to a residential neighbourhood on a hill, through narrow, winding streets lined with elegantly arranged gardens; the houses behind them exude an air of restrained wealth, typical of urban Japan.

Shoei brings us to another house that he designed for his family. It happens to also be his office. The house, a simple two-story volume clad in glass, stands on an elevated terrain surrounded by a small garden, which on the day of our visit is infested by extremely aggressive mosquitoes. Shoei brings us to a kind of underground depot, where he starts to show us presentation panels, some study models and framed print-outs from his website, where he has expressed his design philosophy. The den is hot, windowless and it seems that the insects followed us in there.

Greg and I, still frustrated, ask if he has by any chance some notes or working drawings. He conducts us into an area of the office (that looks as if it has been largely abandoned) and starts to open cupboards filled with plastic folders. He pulls out five black plastic folders for the Toyama Galaxy gymnasium and for the Odawara gymnasium, the project that Greg originally wanted to display. In the folders are hundreds of computer print-outs, diagrams, and beautiful working drawings on transparent vellum in pencil and ink. Even in the heat and the insects, it is a moment of intense relief. Finally we feel that the trip has been worth it. We have unearthed the hidden treasure and it’s more than we hoped for. Carefully arranged and organised are the documents of several projects that highlight Yoh’s extensive research into light structures, wood construction and tensegrity. These are topographical designs, complex realisations of architectural and technological research that Shoei developed at the end of the 80s and that constitute an astoundingly rich archive of material. Very quickly we are done. Exhausted from the jet lag and itching from the insects, we can return with the security that we have accessed a wonderful archive.

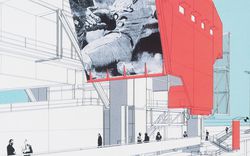

An important cornerstone of the Archaeology of the Digital project has been laid. Greg made it clear that he wanted Yoh in the exhibition from the very start. The Japanese architect’s research in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s was at the time the most advanced point in the integration of digital technologies into architectural thinking. Using software developed by the engineering companies that were involved in Yoh’s projects, he managed to use data to create form, anticipating trends that other designers would explore later. Coming from a different background than the majority of Japanese architects and having decided not to move from Fukuoka, Yoh is in some ways an underdog, although one that is respected by younger generations because he is particularly original in his thinking. There is a strong ethic at its core: the computer was used to optimize structures and thereby use fewer materials to the general betterment of the very nature it mimicked.

Relieved, I return to Montreal by way of Tokyo: to catch up, partially at least, with the bustling architectural scene in Japan. I wander the streets of Shinjuku, Nakano, Yoyogi, Daikanyama and look at the signature architecture in Omotesando. I get lost in the gigantic department stores of Shibuya and their multilayered towers of consumption. The last visit before leaving is the Yokohama Ferry Terminal, designed by Foreign Office Architects. Although underused, as there are not so many cruise ships arriving in Yokohama as had been hoped, it establishes a new way of imagining architecture as a complex gesture that generates a new topography. The building is a landscape that can be approached and explored. Moving over it, the feeling is that the horizontal and vertical planes have merged, as well as the interior and exterior. The execution is perfectly coherent with the design intention as well. Rather than being composed of smooth planes as was the case with the competition entry, the structure is composed of folded concrete surfaces that give the terminal an intriguing roughness. There is a sensuality that one does not associate with digital architecture.

That building could very well become one of the pieces of the next instalments of Archaeology of the Digital. It is an evolution of the paths established earlier by authors like Yoh and it proves that even if it is relatively young, digital architecture has already a history thick enough to be considered in retrospect.

Shoei Yoh’s Galaxy Toyama Gymnasium and Odawara Gymnasium projects were featured in our exhibition Archaeology of the Digital in 2013.