Past(el) Digital

Video and text by Mika Savela

Tadaima.1

“The archive also contains electronic files. These include computer diskettes, zip disks, and CD-ROMs that can hold submitted texts, various photographic images, or research information. Especially significant are three Macintosh computer hard drive cartridges which contain hundreds of Anyone files (some of which may not exist in hard copy) related to all aspects of the Corporation’s activities, programs, and history.”

“Since many of the conference videos were shot outside of North America, the tapes exist in two VHS formats, as copies in the NTSC and PAL standards.”

— “Scope and content,” Anyone Corporation fonds (AP116), CCA

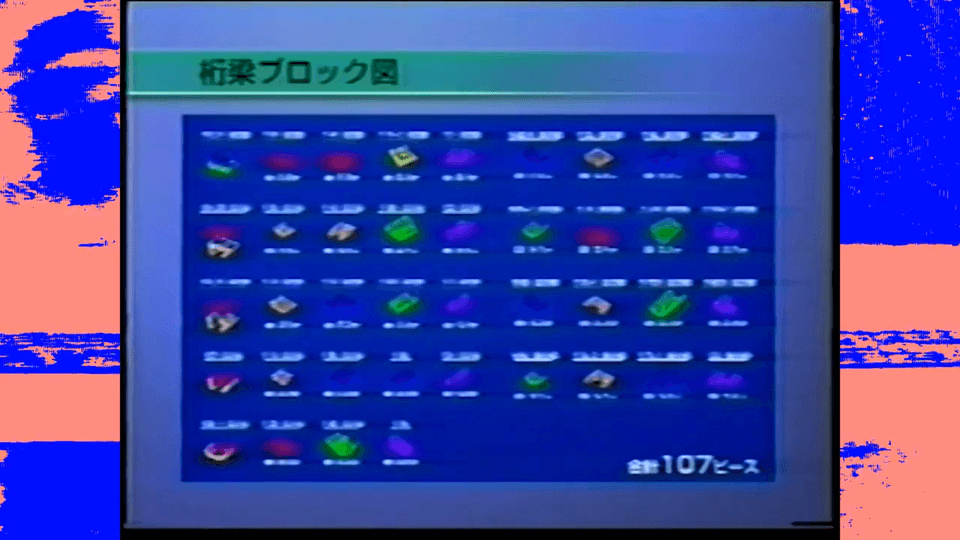

During the era of early desktop publishing, digital image editing, digital office management, home computers, and digital cameras, we became comfortable with tape drives, floppies, Zip disks, CD-ROMs, and videotapes as containers of images. (A Kodak Photo CD could hold nearly one hundred photos!) As digitality became part of a modern consumerist lifestyle, these items were increasingly offered in fashionable pastel-toned packaging. Editors and makers of architecture worked with these objects to create, share, and preserve their images, texts, and designs. And then suddenly, one after another, these things became nearly obsolete.

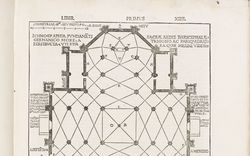

Today, various objects created for the storage of digital files of photographs have entered the archives, as evidence of work that just a few years ago seemed urgent, pressingly current, and supremely professional, and that pushed the envelope in terms of technology. In the context of an architectural archive—which is often rich in photographs that can be perused by the researcher—the new impossibility of casually accessing slightly antiquated digital formats of media foregrounds the physicality of the media’s support and at the same time points to its position in a larger network of contemporary references.

More generally, the visual qualities of the old digital are back. The online presence and sharing of video clips, GIFs, and memes—as well as an expanded technical prowess in producing them—and specific digital cultures such as vaporwave have given the pastels of the digital near-history a new kind of reading. Past(el) digital has become a source for visual cultures that take note of the limitations of yesterday’s technologies.

Perhaps just enough time has now passed to allow the culture of the early web and 1980s look books to blur into a single pool of references. Perhaps this has been fueled by an ironic millennial view of the visual styles of the past few decades as isolated moments, especially online. (Looking at you, aerobics.) But it could be more complicated, or at least in part a sincere effort. Some vaporwave videos demonstrate a keenness to showcase the vaporous emptiness of the material culture of the 1980s and 1990s as relentlessly driven by economic growth, a business agenda, and the globalization of consumer behaviour (exemplified by the use of Asian TV ads in these videos). In this regard, the imagery of vaporwave contains critically inclined but blithely wavy commentaries on the innocent and happy, yet slightly disturbing, exuberance and commercialism of postmodern cultures.

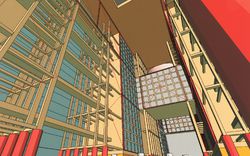

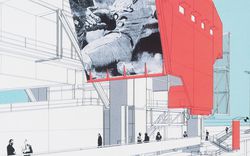

Past(el) digital is a general category for the interests of contemporary visual culture in the early digital era, but there are aspects of this category that relate specifically to architectural practices. Many architects were early adopters of digital imaging technology. While the use of photographs in site research, in photomontages, or simply as sketching references had long been an accepted means of analogue image production, there was an unmistakable drop in the technical quality of photographic content produced by architects following the first introduction of digital tools. The choppy visuals of the early digital era were guided by limitations in technology. Similarly, it took some time for architects to view the Internet as a viable means of communicating visually about their projects or practices. For instance, a strange, prismatic, flash-animated portrait of Zaha Hadid’s face greeted visitors on her firm’s website for years. These “poor images,” as Hito Steyerl has called them, have not disappeared from the economy of images. Today, print and digital publications, exhibitions, events, competition entries, and design choices (such as blue-screen blue) are affected by elements of the past(el) digital. And it is perhaps only recently that the “post-digital drawing,” to quote Sam Jacob, has become a medium that is used confidently in architecture.

In recent years, photographs have begun to be handled without service bureaus or other agencies to manage the distribution, editing, and publishing of images. (See, for instance, Amy Kulper’s research into the history of Photoshop.) The “image independence” of architectural practices is still relatively new, and platforms like Instagram can easily take the lead in visual communication. The printing of images has become cheaper and easier, but the detail and quality of the earliest digital prints pale in comparison with the richness of nineteenth-century photographs. Nevertheless, the poorness of the images made by early digital tools and the limitations of digital photography and its forms of representation have today become stylistic filters and aesthetic references for architects’ images. Image dithering with a limited set of indexed colors, Xeroxing, and dot-matrix printing are aesthetically desirable but technically unnecessary.

The visual style and historical “referencelessness” of vaporwave, as well as an interest in past technological aesthetics, have begun to have an impact on architectural culture. But while the aesthetics have returned, their original references have not. Instead, architecture as image making is following the demands of the digital. It is also guided by the broader interests of visual culture, where the mixture of image sources, quality, and technologies (i.e., Google Street View versus the real thing) continue to prevail. As such, it might be that prowess not in technology but in technology’s cultural context is becoming a means to succeed in architectural practice. The question for architecture becomes What lies beyond this newly developed sense of cool?

-

In Japanese, tadaima means “I’m home” or “I’m back.” ↩

Mika Savela produced this video and text in 2017 as part of a research project entitled “Offness.” This work is the result of the multidisciplinary research program “Architecture and/for Photography” developed by the CCA, with the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.