A Positive Sense of Connection

John Helliwell and Carlo Ratti on better networks

- JH

- The gradual evolution of the psychology of happiness emerged at a time when people became impatient with economic measures, in particular GDP, as a single proxy for quality of life. There had been a focus over the last century or more on level of income in the absence of any other data that was equally as available and understandable. Today the Gallup World Poll, which underlies the World Happiness Report, asks people to think broadly about their lives as a whole, and to evaluate aspects on a scale of 0 to 10. The primary purpose of these measures of life quality is to give an overall measure of welfare. They are entirely based on people’s own judgements, and have the advantage of being reportable at the scale of a neighbourhood, a city, or a country and of being tracked over time. They automatically encompass all aspects of life that have an impact on wellbeing.

- CR

- Additionally, we’re now measuring a lot of things in cities that we couldn’t measure before—data compiled over ten, twenty years, gathered to understand the metabolism of the city. We are looking at many types of big data in the city and, as John mentions, the measures are imperfect but they are the best gauges that we have. We have data that describes dimensions of the city that were impossible to understand, visualize, and analyze a few years ago. And in terms of quantity of data, a new world is opening up due to the convergence of the digital with the physical realms of the cities. With this we may start developing new indicators for a variety of things, including happiness in cities.

Let me give you an example. One of the parameters that often seems to have a big effect on happiness is how integrated we are in our given communities. Being well-integrated within a community, and trusting that community—this is something that makes us feel happy. When looking at cellphone data, you can observe how people connect with each other in a digital communications space and also in physical space because you can see how they move. You can actually see if and how different socio-economic groups integrate in a city neighbourhood—you can measure levels of segregation and integration. - JH

- Exactly. When we do locate the happy neighbourhoods within a city, we find that they are often areas where people feel a positive sense of connection with other people. Two large Canadian surveys and the Gallup World Poll ask: if you drop your wallet with money in it, how likely will it be returned if it’s found by a stranger, a neighbour, or a police officer? The data for how likely it is to be returned by a neighbour turns out to reflect the level of satisfaction with one’s life. People want to live in a community where they think other people are not just honest but eager to help their neighbours.

- CR

- In addition to feeling that one is part of their immediate community there’s a broader urban condition of inclusion or exclusion from other parts of the city. Now it seems to me that globalization is fueling a lot of discontent in countries all over the world, and that the Populist movements that we are seeing everywhere channel a kind of discontent that seems to suggest that even though you’re exposed to many kinds of communities, somehow you feel excluded from them. You feel excluded from the very rich, from the top one percent.

Conventionally, many things follow a precise law—it’s called Zipf’s Law. George Zipf was a statistician and mathematician working at Harvard in the middle of the 20th century; he proposed that in any language, the frequency of the most frequently used words was inversely proportional to its ranking. This law was then noted in other rankings, like rankings of income, city size, and other urban parameters. Now with globalization it is almost as if Zipf’s Law may be applied to the planet: the extremes are further apart but inversely more visible. You might be in the middle class and you’ll witness and follow the lifestyles of celebrities and the super-rich and you will continually see that you are excluded. I believe this in turn generates the Populist discontent that we are witnessing.

So one question I want to ask is: a lot of this is still based on metrics related to wealth, so even though we’ve moved from using GDP as a close proxy of how a society is doing, is it possible to turn monetary metrics into something else through big data? And could we find new measures of impact that stand on our ability to measure things that we couldn’t measure before? For instance, is there a new metric that may allow a teacher to feel much more accomplished because their impact is huge if you consider that they are educating new generations that go on and change the world? Because, you know, that is certainly not captured in coarse monetary metrics as they are used today. - JH

- One thing that neither of us has mentioned yet is the importance of distance. We know from many decades of study that, by and large, contacts become less dense at higher levels of distance. A simple gravity applies to all kinds of linkages. Of course it now has different dimensions, because we can add kilometres as easily as metres with modern technology.

There was a very nice Léger poll a few years ago that asked people about the size and frequency of use of their networks of in-person friends and their networks of online friends; it found that the bigger your networks of in-person friends and the more frequently you saw them face to face, the better your life evaluations were. We found absolutely no such relationship with the size or intensity of networks of Facebook friends. A lot of people use online forums as a substitute when they don’t have good in-person connections. There are some subgroups that in fact seem to get something net from the use of less personal forms of connection in terms of quality of life, but on average over the population these online spaces have done nothing to increase the life satisfaction of those who are heavy users. That then poses problems, whether they’re for families or schools or individuals trying to manage their use of networks in a way that actually yields better connections rather than worse ones. - CR

- You are reminding me of this beautiful book by Peter Singer called The Expanding Circle: Ethics, Evolution, and Moral Progress. Singer discusses these circles of empathy that show how we relate to our social surroundings and thus show the positive connections that we have around ourselves. I’m extrapolating and not quoting him here—if these expanding circles become too large or unbalanced, we create a lot of stress, and people become very dissatisfied in bigger cities.

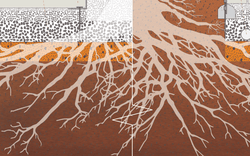

And so there is importance in having our connections follow a kind of hierarchical or fractal pattern: how can we make sure that we connect with the right sensitivity to different levels of society? In big cities, for instance, if you feel like an individual in a community of millions with no supportive connections, you will feel a smallness. And so I think it is a very interesting design question for all of us as architects, engineers, as planners: of how can we build cities that absolutely facilitate a kind of fractal tree of connections? - JH

- I’d like to support what Carlo is saying here about a city as not one community of millions but a community of communities, because it’s inevitable that life is inherently local and it is the people you actually see and connect with in a very direct human way that are primary. You naturally want circles that connect with other circles, and the beauty of modern technology is that it allows you to have close personal connections while maintaining more distant ones. In fact, it should be possible in cities to at once exploit a capacity to work at long distance and also join people on a face-to-face basis in social and other environments, allowing you to have the best of both worlds.

I’m absolutely sure that a tight community structure—what’s present in lots of Italian cities, for example—is something that we don’t want to lose. A number of the big western cities, as they’ve gotten bigger and more prominent, have become more segregated by income and occupation, and the capacity to know neighbours and to connect with people in a positive way has diminished. You either have to work harder at building those opportunities for yourself or to think of some redesign that will allow local communities to be just that. It means you then have to deliberately ensure chances of shorter and better commutes, increase the chance that you can live and work and be educated in the same neighbourhood, so that you can make these connections automatically.

There’s a second element—it’s that some of the connections that are vitally important for humanity extend across ages, and modern families tend to get separated geographically. Thus what used to be the classic social unit (the three-generational family) is now disrupted: children are placed in daycare centers and the elderly are in elder care centers, and for that reason alone both groups lead much less happy lives than they should. In terms of social innovation, there are now plans to run daycare and eldercare facilities in the same space to allow the elders to teach and enrich the young and the young to enliven the elderly to recreate in an urban mixed setting the kind of joy that traditional family structures would produce. So that’s a type of social reorganization that has architectural implications. There are a lot of modern co-housing models in Canada, where they’re deliberately designing multigenerational living units—so you’ve got built-in babysitters and all the things that a small community or a functional family would have. Through design parameters, you can mix private and shared spaces to allow these living units to cooperate and of course, you could do the same thing at the neighbourhood and community level, as well. You can imagine the kinds of spaces that can be converted to shared use and what kind of shared uses you might find.

I think of it as establishing positive social identities of several different dimensions. You want a connected family to be living in the midst of a connected community. Thinking at the global level, it’s quite clear that in order to sensibly address global threats like climate change, we have to develop a sense of an even bigger community—a social identity that encompasses not just tribes and other people in your city, but other people in your country, other countries in the world, and other generations in the world to come.

Robin Dunbar is doing powerful work in evolutionary biology at Oxford where he ranks different mammalian species by the size of their neocortex and associates that with the group size with which they can interact. There is a notion that, for each mammal, there is a group size for which you can carry in your mind the information that allows you to collaborate with others. Well, quite clearly our neocortex is not expanding at the rate required to give us the ability to accommodate the millions in cities and billions in the world, so we now require a construction of social institutions that provide a sense of familiarity with others so that it’s easier to interact with them as with kin, family, or neighbours. - CR

- I think Dunbar’s work on this number—this number of contacts, what is called Dunbar’s number—is very interesting. And I think he probably doesn’t know whether this number is coded within or if it is subject to change.

Let me give you an example of something that has been changing due to boundary conditioning and interaction—James Flynn, an intelligence researcher in New Zealand, discovered that IQ scores across the world are constantly increasing. I remember him telling me about thousands of different correlations, and nobody really knows where they are coming from—but they are certain it’s not from changes in biology. The changes in IQ have been too quick; they cannot be explained by changes in our brain. The most likely correlation was that with urbanization. You’re in an environment that’s more diverse with more stimuli, and that changes our way of responding to the environment. This is basically what IQ measures: a kind of intelligence that’s related to how we respond to a number of external conditions.

And so I’m wondering if Dunbar’s number is similar, if it might change with new conditions. Maybe in the old village, Dunbar’s number was exactly the number of people you would interact with in the village, but today the number could contain different communities from the family, the local community, the city community, to the global one. That can support the allegiances that, as you were saying John, are vital to our survival if you want to fight the big challenges of our time: climate change, AI transformation of the workforce, etc. - JH

- Absolutely.

- CR

- Certainly it’s the only solution we have for our planet; at some point, with this expanding circle, we will truly feel that we are all together as if on Buckminster Fuller’s spaceship earth. And a quote comes to mind. He said we need to decide if we want to be architects of the future or if we will be the future’s victims. We really need to play with our new tools, understand their positives and negatives, and master them.

- JH

- I absolutely agree. And as we begin to wrap up, I think it’s worth restating explicitly that the recognition of the primacy of social connections as drivers of human progress was a revolution in the work of researchers of well-being. And without the data from the wide collection of subjective life evaluations, we could not have measured the impact of things like income and consumption against the quality of social connections. It enables us to talk about different neighbourhoods, cities, and countries. We can find out enough about the networks in which people live and work to figure out which aspects are most important, and it helps determine future trajectories for our technologies.

The power of the social is what our contemporary moment has brought to center stage, where it never was before, and it will be hard to push it off. - CR

- I think we’ve always been struggling for this. If you read Epicurus, there’s a part of his writing where he said what we must investigate what brings us happiness and unhappiness and try to remove the unhappiness from our lives to increase our happiness. This has truly been our goal forever, and we’ve been doing this over the years with different metrics. It seems that what we are discussing today is something that has been on the agenda for thousands of years. And today will always have new relevance because of new knowledge and new data.

John Helliwell and Carlo Ratti spoke with Francesco Garutti in advance of the exhibition Our Happy Life.