This narrative fiction concludes both the online issue Will happiness find us? and the book Our Happy Life.

This Home Will Make You Happy

Text by Ingo Niermann

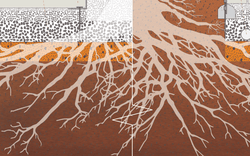

Apes sleep and hide high in trees where they gain an overview of the landscape and are safe from predators on the ground. For similar reasons, humans first seek to sleep and hide in or on top of mountains. Later, able to build massive walls, they erect fortified castles and towns as a mountain substitute. Just as agriculture gains importance and fields are expanded through irrigation, towns, and then cities, grew with the help of a sewage system. The best location becomes the one next to a river: a source of water and a means of transportation. No longer shielded away, the city exposes itself as a trading hub to strange goods and people. People don’t defend themselves where they accumulate, but telecommunication and division of labour allow them to be defended at far-out frontiers. Garbage, decedents, prisoners, beggars, factories, wars—everything uncomfortable is taken outside.

The bigger a city, the likelier it is located at the mouth of a river, next to the sea. Even if most inhabitants of a city stay there all their lives, its economy is based on trading, migration, and traffic. No matter how generously a city is designed, sooner or later its growth makes it congest. In response to the limited space, sight, and air of the city, the middle class escapes on iron horses to suburbia, where their single-family homes allude to tiny castles. The wealthiest find relief in the wide open of the sea, where cruise ships offer the comforts of the city and yachts the comforts of the villa. On land, modern villas with plain facades and plentiful terraces imitate yachts. Skyscrapers with sleek, glazed facades resemble upstanding cruise ships and compete for a free horizon. This city is to the skyscraper what the ocean is the luxury liner: a glittering carpet, to gloss over a suppressed other. You need evolved security systems to feel safe enough to ignore it. Naval accuracy leads to urban zero-tolerance.

In a next step, high-rises are also built in suburbia (in particular in socialist countries) and cruises also offered to the masses (in particular in fascist Germany)—imbuing everybody’s life with the flair of the sea. The rich move on, building the facades of their villas and skyscrapers out of glass and sobering up their interior design to make even the inside look like life on deck. The less wealthy who work on the lower skyscraper floors or who install glass facades on their suburban premises pay with lost privacy.

Today tens of millions take holidays on cruise ships that resemble floating carnivals. They flood coastal cities and indigenous villages by the hour, turning them into theme parks likewise. Multi-billionaires equip their mega yachts with conference rooms, helicopter pads, and dozens of bedrooms. Still, only a very few have made an effort to live permanently on the ocean and use its extraterritorial status to their advantage, like the Women on Waves abortion ship, rescue boats for refugees, or L. Ron Hubbard’s elitist Sea Org. Keeping up with urban standards of living on the ocean consumes a lot of human and natural resources. Traditional sea nomads can sustain themselves on tiny vessels for a longer time than modern adventurers on multi-million-dollar yachts. The ambition of the Seasteading Institute to build offshore mini-states on movable platforms comes with all the charm of an aquatic trailer park.

The conception of a permanent life on the ocean becomes a model for life ashore. The rich treat the places and nations where they live as free harbours—they expect tax exemption and are always ready to leave for another, more favourable hub. Accordingly, new luxury real estate is often located in former harbour buildings. The property comes with internationally standardized facilities; local characteristics serve as mere decoration. The less wealthy acquire this flexibility only in the virtual infinities of the internet. Here they can be explorers, pirates, or traders. Similar to traditional sailors, both rich and poor tattoo signs of particular moods, thoughts, or moments onto their skin to give their life some significance.

With cities, world population, and traffic rapidly growing, even the space in the sky and on the ocean turns out to be limited. New technologies like satellites and drones allow ubiquitous surveillance. Pollution and climate change happen more or less everywhere. Prices for centrally located real estate with privacy and a view are skyrocketing. For many people their home is the one major investment that dictates their whole life (economy, job, love). Rather than steering the boat, we are jumping aboard before it’s too late, uncertain where it will take us. A home serves as a shelter against a world that is shaped by the struggle to pay for that shelter. The bigger our home the more stressed we are to hang on to it—too exhausted to really use it: bigger beds go with less sex and sleep; bigger kitchens with less cooking; bigger living rooms with less socializing; bigger windows with less looking outside; bigger terraces with less being outside. The only home activities that are increasing don’t really need space or even deny it: watching television, going online, computer gaming, and meditating. The more importance we give to our home the more it becomes a mere museum of being at home—real estate advertisement doesn’t even pretend it’s anything else. This museum is empty, missing its crucial piece: us. Still, to accommodate us within its confines, this museum guides us—through design and computer control—to live in unassuming ways: pale colours, sound protection, smart temperature regulation, smart shading, automated fridge refill, high-speed internet, burglar protection…

No boat or home can be completely shielded. Storms make them shake (the higher up we are in a ship or a house, the more it moves), natural catastrophes (hurricane, ice storm, earthquake) might affect the supply of food, energy, or internet, and a sudden attack (robbery, war, revolution) might make it impossible for us to escape.

On a boat we are usually more aware of the fragility of our relationship with the environment. However big, a ship is never completely still; we are surrounded by life vests and life boats; there is no police or army to immediately protect us; we know that we can’t swim that long; and we don’t have to dive or be heavily rocked to know that we are enclosed by an entity far bigger, far more potent, and far more complex than us. Even if all windows were darkened and the sea were completely quiet, we would still know that it’s there—it’s implicit, like the way we know our bodies. Only, the oceanic environment is utterly alien.

The vastness and strangeness of the sea brings people on board a ship closer together than on land. Space is precious, it needs far more people to maintain a boat than a house or apartment, and they—occupiers, employees, and guests—are all stuck together for some time. Being together in a heavy storm on a yacht resembles an Ayahuasca session: it starts with a phase of denial (“It’s not that strong. It’s maybe even boring”), followed by nausea and lots of vomiting, finally turning into a mind-altering experience. We start to sense a rhythm in the constant up and down, back and forth, left and right—only for it to be broken the next moment by a surprise move. Some oceanic moves are subtle and trick us into counterbalancing them too much, others hit hard like in a massive collision. We are all struggling with the storm pretty much on our own, but as soon as it weakens we bond and hug each other with a new intensity. On board our balance system seems right again, but back on land everything is shaky.

In the last years, collective gatherings based on a sort of temporary self-arrest, such as Ayahuasca sessions, transgressive festivals, LARPs, or escape rooms, gained popularity. New technologies of renewable energy production, recycling, urban farming, and 3D-printing offer scenarios for these gatherings to be completely autarkic. Focusing on the boat experience as an intense collectivity—not just as a segregation from the masses—could help to evolve this approach into new practices in our homes to turn them from monuments into actual facilitators of well-being. How could you commit to leisure trapped on a boat if not by having a great time?

Even though being happy has become a major moral imperative and there are more—commercial and non-commercial—offers than ever to help us achieve it, we lack routines to actually be happy rather than gather things and experiences that we associate with happiness. Our feelings are as private as we can get and our home is the perfect place to explore and steer them. On a boat, every trip is a bit of a new beginning—an ark—for which we have to decide with whom and what to be. We could do the same at home: every now and then we could make a cut at which we decide anew who/what stays with us and who/what is acquired or invited to join us. We could have people (friends, lovers, strangers) and things (acquisitions, gifts, surprises) with us as guests for a predetermined period of time. We could shut the doors and disconnect the internet, phone, and television to turn our home into a lab. Or we could allow ourselves to leave home only in ranges of a certain size to surprise ourselves like on a diving excursion. Alternating between phases of dense encounters and experiences and phases of solitude, our home could transform from a place that is safe but boring into a place of sustainable adventure and activation. Here we could dare to meet new challenges and confront inner obstacles.

This new, even more ship-like, relation to our home could in turn effect our recreational use of ships. Freed from the necessity to dock now and then for supply and disposal, cruises could completely abandon the shore. No longer reliant on sucking up the vital energies of hundreds-of-year-old cities and thousands-of-year-old cultures every other day, cruises could develop the perseverance to drill us into experiences that feel larger than life. Amidst the shimmering waters that are the source of our attraction to glitter, cruises could become a non-stop variety show of impostors, love divers and love doctors, beautiful words for love, happy love, singing flowers, luscious people of all ages, mysterious entanglements with distant Siamese twins, hypnotized pets, love and all about love, every walk dancing and kissing and loving, more kissing, stupid and hyper-intelligent love again, idiocy and a smile, breathing bliss, and love, only love.

From the very beginning shelters haven’t just been places that protect, but places where animals gather to communicate, love, and gain new strength. Voluntary fate, the kind found on a cruise, can help us recollect these functions in our homes and make us happy.