Darkness, Silence, and Nature as a Political Plan

Renato Soru on landscape and happiness, interviewed by Francesco Garutti

The founder of Tiscali, an Italian telecommunications company that aided the spread of the Internet and digital technologies across Europe, Renato Soru entered politics in 2004 as the president of Sardinia, a Mediterranean island at the center of the European debate on the relationship between tourism and growth.

In 2006, Soru enacted the Regional Landscape Plan, a policy rooted in a set of values that not only covered themes of environmental protection and sustainability, but also promoted an understanding of landscape as historical, emotional, and integral to identity formation. Themes such as absolute darkness, silence, and the full conservation of natural elements were generative principles of a vision that became a masterplan of an exceptional territorial scale. Soru recently spoke with Francesco Garutti.

- RS

- When I became the Regional President in 2004, I did not have a political background. However, I did have experience with Tiscali, conceiving a new company for a region that has always been somewhat isolated from the rest of the world. I never thought about the company as belonging to an exclusive group of people, nor did I see it as exclusively mine. For me, Tiscali was an enterprise with strong ties to our island, our region.

This was how Sardinia—a separate geographical entity, marginal to some extent, with a history of isolation and underdevelopment—found itself a lively node of the digital-communications web, at the center of major processes, on the same plane as more developed countries.

Together with others, I lived this great experience—this sweeping shift toward the digital, the web, the Internet. Perhaps simplistically, we saw it as an opportunity for libertarian and democratic change—everyone could play a role on equal terms, based on their own expertise, creativity, and willingness to get involved. We started from the viewpoint that the idea of “resources” had ceased to mean only material resources in the ground or great accumulated wealth. For us, the world was a place of knowledge, of know-how, of inventiveness, and creativity. Creativity, art, and innovation mattered most. Opportunities were offered to everyone on an equal basis.

In that period, I kept two articles on my desk by two personalities I felt particularly close to, each of whom I considered in some way to be a mentor. One was by Renzo Laconi, a Sardinian politician and founding father of Italy. Laconi wrote a beautiful article on rural Sardinia that focuses on how a pastoral society (which accounts for much of our identity—they say that all Sardinians, if not the sons and daughters, are at least the grandchildren of shepherds) could shift into the modern world and become timely, important, and significant in today’s society and economy.

The other was by Giovanni Lilliu, father of modern archaeology and the study of Sardinia’s Nuragic heritage and the first to address heritage in a systematic way. The development of this civilization, with its rural culture dating back to 2000 BC, was interrupted by the Phoenician and subsequent Carthaginian invasions of Sardinia—the beginning of a long history of dominion over our land. We can say that the Nuragic culture was “killed” precisely when it began to evolve into a more organized urban culture.

To some extent, we Sardinians have never gotten over that grief. We talk about ourselves with a certain sadness. Our color is black, our idioms are more about lamentation than celebration or joy. Our songs are funeral dirges, our oral tradition is all about despair, emigration, defeat. Lilliu wrote that it was time to get away from that mourning, to process it, to stop presenting ourselves in such a sad, sorrowful way, and to instead represent ourselves “with colors, the colors of joy and happiness.” To put mourning aside and to “strive for happiness.”

So, in the early 2000s, at the start of mass digitalization and my political appointment, I saw an opportunity for this transformation. We wanted to leave behind the archaic and move toward a new vision of the world. - FG

- Are these the themes that led you to get into politics and to reimagine the very idea of landscape in Sardinia?

- RS

- As I mentioned, I was outside of politics, but I was asked to get involved. I resisted getting personally involved for quite some time, but I was already taking part in debates on environmental protection, on the coastlines, and on sustainability. At a certain point I realized that I could stay out of politics, but then, if things went badly, I couldn’t complain about it because I’d turned down the opportunity for direct action. In effect, the protection of our regional landscape and environment was the catalyst for my entry into politics.

- FG

- In a wider context, this was when Al Gore, known for his reflections on environmental quality, ecological disasters, and sustainability, was running for President of the United States.

- RS

- Yes, and when Joseph Stiglitz’s analysis of globalization made us think: in this “great and terrible world,” as Antonio Gramsci put it—at the time we liked that phrase—what role could we assume? What could be our contribution? What would we have to focus on in order to live better, to be happier?

- FG

- For your electoral campaign, your proposal was to imagine Sardinia as a model of pristine, pure nature. An island, an environmental preserve.

- RS

- Yes. Sardinia definitely has its own character within this beautiful but delicate Mediterranean region. If you look at the sea from the sky, it really seems like a small lake. The Mediterranean was and is in danger because masses of people that once lived inland now live on the coasts. Often, especially in the South, these inflated cities do not have water purification systems; they discharge anything and everything into the sea, risking the rapid destruction of coastal habitats and sea life.

In Sardinia, we had the will and need to curb real estate speculation, particularly on the coast and in tourist centres. Speculation at the time was unrestrained and the law allowed total freedom of construction on private property. Private use was favoured over the idea of the landscape as a common good, even in ecologically delicate areas that should have remained in the public domain.

An attempt at the environmental protection of the Italian coast was made in the mid-1980s with the Galasso Law, but in the early 2000s, many territorial-landscape plans were declared illegitimate by the TAR (the regional administrative tribunal) and the Council of State, seriously weakening this important landscape-protection tool.

Around then we realized that a few hundred million euros would suffice to purchase what remained of the Sardinian coast, almost completely removing it from the market. And this privatization was probably inevitable anyway, if we consider the expanding market for vacation homes. We foresaw that, in a short time, everything would be lost, and we would become an island of regret, of remorse.

- FG

- So what did you decide to do about it?

- RS

- It was necessary to propose general rules from the outset—the coastlines were something of a new Wild West. We took advantage of existing urban legislation that granted the regional government the right to block building permits for three months in cases of serious, irreparable damage related to the work in question. We extended that principle to the entire two thousand kilometres of Sardinia’s coast. We took the radical step of saying, in Sardinia, for the next three months, all building permits are suspended. You cannot build anything new. Nothing at all.

These three months blocked activity and let dust settle enough to approve a transitional law, the “Legge Delega 8,” that would grant us eighteen months to construct the Regional Landscape Plan.

Naturally, this triggered extensive debate and criticism. Blocking construction for so many months along the coast seemed like madness. But the Regional Council managed to pass the act and to then complete the Plan.

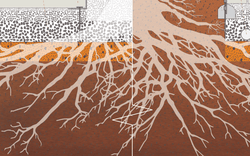

To study the Sardinian landscape, we appointed a committee of experts, chaired by the urbanist Edoardo Salzano, and we called in archaeologists, naturalists, sociologists, and art historians—any necessary expertise. Then we divided Sardinia into two areas: the coastline (up to twenty km from the shore) and inland territory.

We began with the coastline, which until the 1950s had been abandoned and unhealthy—these were places where people died from malaria. As the story goes, the nonarable land closer to the sea was once left for women, precisely because of its low value; these women then became unexpectedly wealthy by selling what are now some of the most coveted coastal sites: Liscia di Vacca, Capriccioli, and Porto Cervo.

In the following decades, the coastline developed due to tourism, often paired with relatively unsightly real estate speculation. When we added things up, we realized that half of the coast had been eaten up in this way, but the other half was still intact, uncompromised. - FG

- You often speak of Sardinia as a “land of silence,” and of dense, deep darkness. With the Regional Landscape Plan, you blocked construction on the coasts and put forth a new idea of planning far in advance of the many sustainability, mental well-being, and happiness-focused agendas defined by the political protocols of 2008 and the years to follow. I’m also thinking about the 2018 French legislation on light pollution and the controversial notion of “darkness” in relation to security and environmental quality mentioned in nearly all the national reports on well-being today.

- RS

- Sardinia has large open spaces of very low density, places of pure landscape as far as the eye can see. A big void also means darkness, as you don’t come across light for miles and miles; in some areas, there are no towns, no human presence. For Mediterranean Europe, these are rare and special conditions: wide-open spaces, boundless views, darkness, night, silence. We thought these were identifying values on which to base the political project of the landscape—values for the future, for urbanized people who no longer perceive the darkness, who no longer see the stars. By now we are accustomed to excessive public lighting and we have set ourselves rules that at times seem like the result of political and economic folly, the result of lobbying by electrical utilities. To cite a positive case, I was impressed by the beauty of the city of Basel’s nocturnal lighting, which is controlled and unobtrusive and lets you really feel the night.

The Regional Landscape Plan comes out of all this, a model for an entire region that departs from the touristic exploitation that was recently so pervasive.

Renato Soru spoke with Francesco Garutti in advance of the exhibition Our Happy Life.