Dealing with Reciprocal Realms

Gary Hilderbrand and Kiel Moe discuss the certification of happiness

- KM

- Our Happy Life does a great job of landing the point that many private certification programs do tend to start from Wall Street or the real estate industry. For instance, LEED’s origin was in a conversation of developers trying to can lease more office space during the early ‘90s recession. Someone raised their hand and said, “We could tell people that it’s green,” right? That’s why the early LEED system was all about replacing carpets, changing wood veneers on doors, and adding bike racks—the easiest things you could do to any office space to brand it some other way.

Certification programs share a story about monetizing the environment, or happiness, or experience, or sustainability. The program goes through a blender with some science, some peer-review, and some input from architects and landscape architects. In my view—after we’ve been doing this for a few decades—it seems like these programs begin to bias certain types of building products and building systems. And it has created a disabling profession of experts who comment on all these sorts of things. So I do see it as a historical phenomenon that’s transforming practice. In the early days of your practice, you weren’t doing any of this, right? - GH

- Not in the beginning, at all. I guess starting in the early 2000s, we suddenly had to have sustainability consultants. I’ll admit that it took me a while to embrace the term “sustainability” because my suspicions about the rating systems gave the word a diminished value. I’d always felt that as landscape architects we inherently work with the idea of sustaining living landscapes and so, honestly, I put a barrier around the term, while in fact engaging most of the practices that LEED sanctions.

But what changed me on “sustainability” was that our clients began demanding it. We couldn’t operate without demonstrating how we were practicing it. Now, in the present, you’ll think that I drank the Kool-Aid, especially with this one program—the Sustainable SITES Initiative. SITES originated in the American Society of Landscape Architects itself, the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, and a few other partners. Here you had people with a real agenda around adaptability and locality, around choices about where a project’s labour force comes from, where its products come from, how far things have to travel during construction, and how a landscape performs after it’s lived in.

I’m also quite convinced by the Delos Rating System called the WELL Standard, which impresses me with the kinds of things they rate. There are mechanics of measuring, and then there are qualitative things that are not impossible to measure but are less objectively assessed. I am really drawn to the fact that the WELL Standard asks us questions about noise mitigation, about how far one has to travel to find a real supermarket, whether good options for fitness and health and life-long learning are available, about the distance one has to walk to get to your voting machine. And these I think are way more related to things beyond the money-driven decisions on the part of developers or even aesthetic decisions or technical decisions on the part of the design team, but rather on whether you have the conditions needed to build viable communities and to support human comfort and well-being. - KM

- I think that it’s certainly been a concern for me that many forms of certification are little more than alibis for neoliberal development. It’s clear how WELL goes beyond that, but it’s also very clear that it is a form of human exceptionalism. It’s all about the wellness of the human being. And that’s why I love that your part of the exhibit is supposed to be about the provision of shade but is actually about tree roots and soil. WELL only wants to know how a person is going to benefit from that root structure, but I want to know how WELL goes beyond the human.

- GH

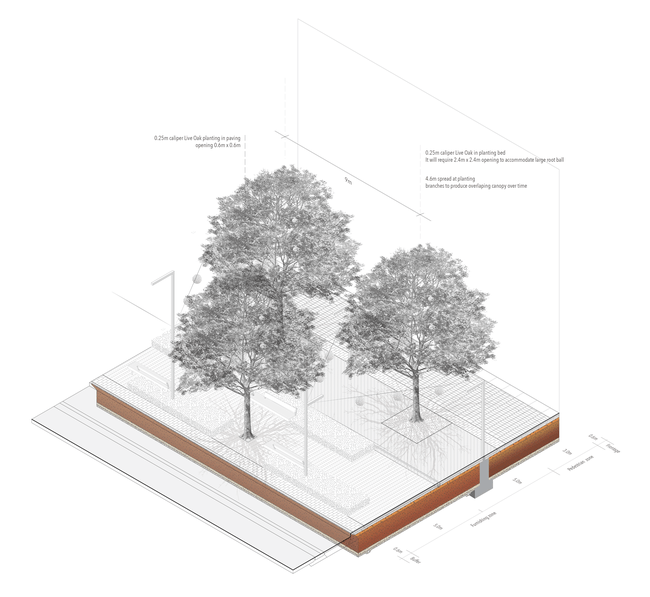

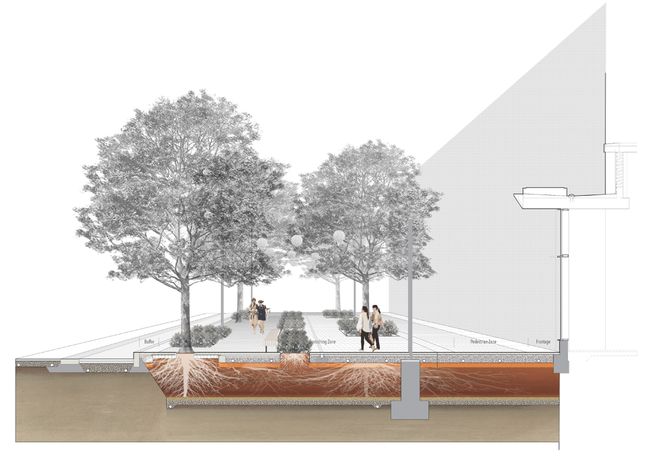

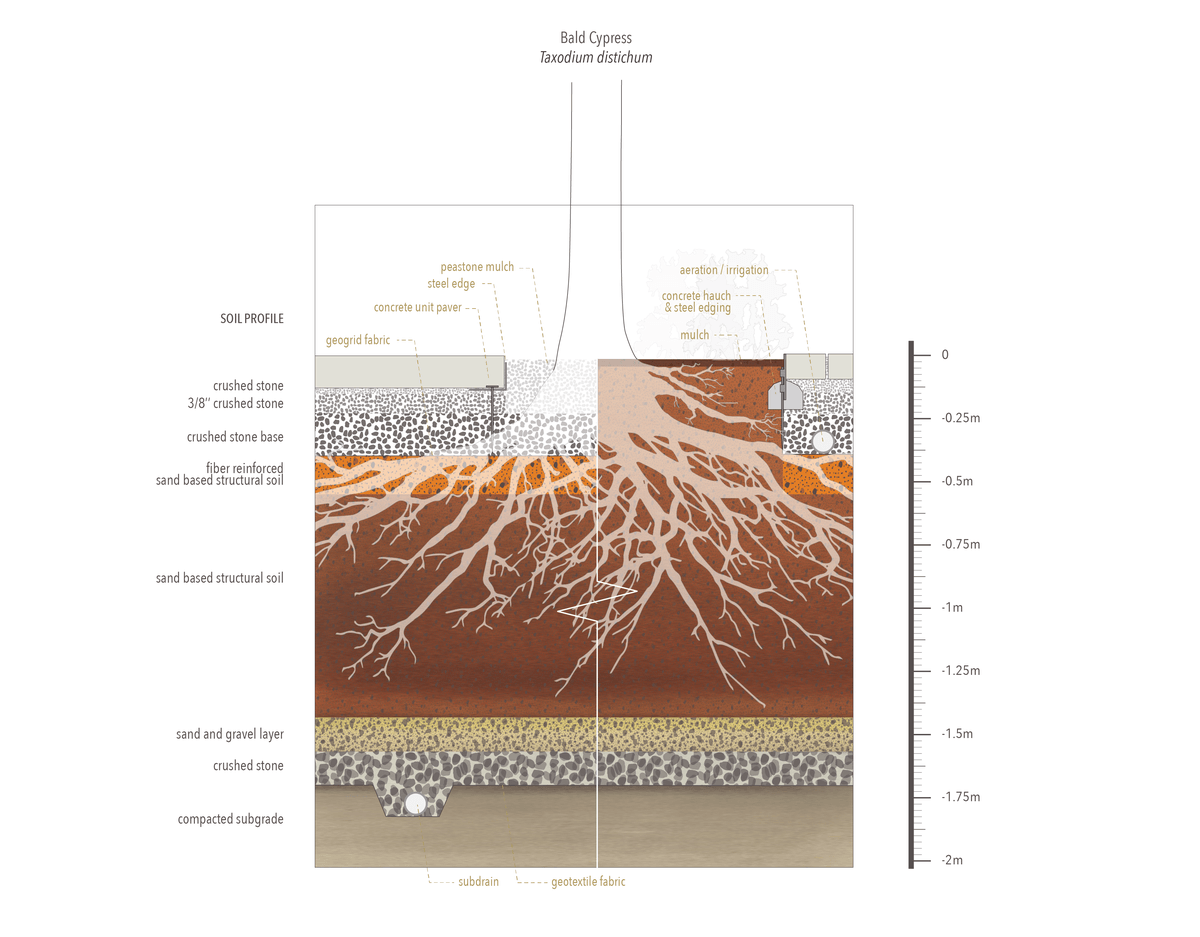

- For the Tampa Water Street project, which we were grateful to see included in Our Happy Life, we guided our development team towards a real commitment to providing shade to the public realm in an expansive downtown neighbourhood of more than twenty blocks. Tampa is a place where you really need shade. So we pushed our soil scientists, our arborists, the engineers and architects, towards what’s needed to sustain the life of a mature tree in a highly exotic downtown environment. We are really quite devoted to having everyone recognize that we’re dealing with reciprocal realms: We have the spatial world of the street and sidewalk, that we walk on—which needs to be cool, which needs to perform lots of functions like evapotranspiration, taking up stormwater, pollutants, and all that. Below that surface, we need a living infrastructure that tries as much as it can to duplicate what happens in the condition of tree and soil interactions in nature. In the city, it’s not natural soil at all, it’s manufactured, and we have to replicate and accelerate the natural, nutrient cycling that is characteristic of plant-soil interactions almost everywhere on the earth’s surface. It’s what keeps the world breathing.

And so in Tampa, one of the first things we did was that we re-engineered the street dimensions, the utility locations, the drainage and sidewalks. Seems like simple stuff. But I find that this is just a very interesting and sophisticated thing to work on. The aim of which, of course, is to produce a vital, exciting, urbane environment which also provides an experience of nature. It’s a very big commitment, and we’re working with the City to alter their standards for the dimensions of streets, the alignment of sidewalks and crosswalks. There’s a lot of intricate detail that goes into producing a lasting shady street experience.

- KM

- For decades now, I’ve learned so much through your details, but specifically from the details of your details. This explanation, that shade takes space above, takes space below, but it also takes time…there’s a time vector to this, and I’m curious about how your details and WELL work with or contradict one another…let’s just say if Tampa gets hit with a hurricane: is this part of the thinking that goes into your design? Because, through some of these metrics, I’m worried about us treating present happiness as a colony of future unhappiness or something like that.

- GH

- So I would say our first order of business there is to have surfaces that drain properly and a good stormwater system, with building platforms that are elevated above the five-hundred-year storm level. And this is really how we have to think with every coastal environment. The second thing is that we now have to design a soil that can be rinsed. And to use a species that is accommodating to a minimum of saltwater intrusion. So that would mean we eliminate lots of trees we might otherwise want to plant. In Tampa, we’ve produced a gradient for planting. We use about nine southern tree species, some of them in a more upland condition, others in lowland conditions where they will be exposed to potential inundation in storm surges. With respect to the soil environment, we’re doing everything we can. And this puts Tampa on the path to climate adaptation in one of the places where it counts.

- KM

- It’s inevitable. Again, and for me this is where the human exceptionalism of WELL strains against its own goals. Because when you to describe how you’re going to achieve shade for somebody who’s going to a baseball game or shopping, you are describing a multi-species interaction, microbes, plants, trees, right? To me, it’s philosophically, intellectually, so anachronistic to just think about humans—and that’s one reason why I’m so glad your tree-soil details are in the show. It gets them thinking at a much broader scale.

These certification programs go project by project, treating them as a performative object that’s made more efficient or more comfortable, but the key questions are in these much larger questions that are multispecies. One easy critique of the certification programs is that they’re highly reductive and they tend to lose the rich complexity of the spatialities and temporalities that you’re talking about.

- GH

- We have to say something about accountability here, too. Because one of the reasons that the rating systems have come about is that everyone, in a world where resources are limited, is more accountable for what they do, right? Sure, we can see certification programs as maybe less effective and perhaps onerous and costly if they get too reductive, rote, and institutionalized. But they’re also beneficial. I do find that some of the people who work in this vein are really creative and the prod us towards better solutions.

- KM

- I love that you are bringing up accountability and accounting because for me that’s a rich term. For me, that word kind of starts with Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society and his explanation of it as a sociological phenomenon and how we’re connected, basically, through the management and accounting of risk. In much of my research work, it becomes almost exclusively about accounting for how much of this stuff comes from this part of the world, if there are ways to reduce the social, ecological, economics—

- GH

- The carbon footprint, social costs, labour and capital inequities, and so on.

- KM

- We have to understand that we are building and designing a world of uneven ecological or unequal economic exchanges—speaking designer to designer, I want our accounting to occur at these levels, whereas for WELL or LEED the issues don’t really come up. One thing that’s maybe not fully legible in Our Happy Life is the spectrum—let’s say the spectrum between a neoliberal capitol of capital like New York City and the other end of the spectrum, which could be the human rights violations in the extraction of cobalt in the Congo or something like that. Our growing lithium economy—we’re trying to legislate green jobs and equitable conditions in the US—that will all come at the cost of more extreme cruelty and poverty in other parts of the world.

Aesthetic experiences of this century are going to be evaluated on how all of these things relate because they’re going to start crashing into each other in increasingly intense ways—and that’s why I’m asking about this imaginary of the Tampa district? Is this going to be a place where people collect and re-organize life because it has soils that drain well? If you want to talk about wellness, I think you have to understand all of that and likewise, you can’t be soil-blind or plant-blind.

Ultimately I love that the image of the Lehman Brothers office—the failure of neoliberalism—is used as the beginning of Our Happy Life. It’s brilliant. And then the show ends, basically, with your details in Tampa. That curation completely blows my mind. And it’s a huge takeaway for me from the show.

Gary Hilderbrand and Kiel Moe spoke in August 2019, while Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism was on view.