Land Sea Land

Alena Rieger looks to erode the distance between places

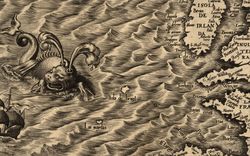

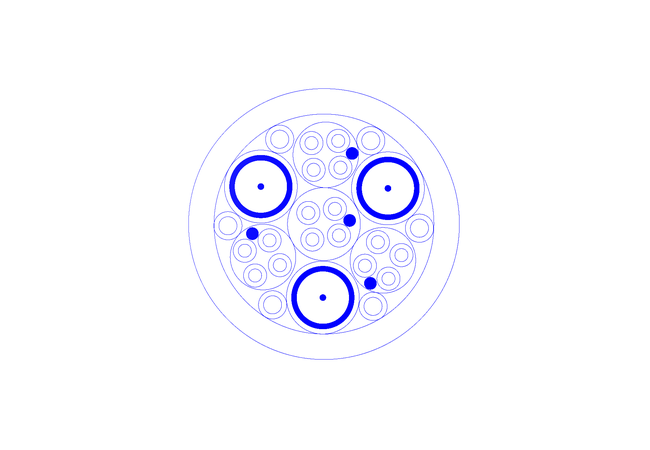

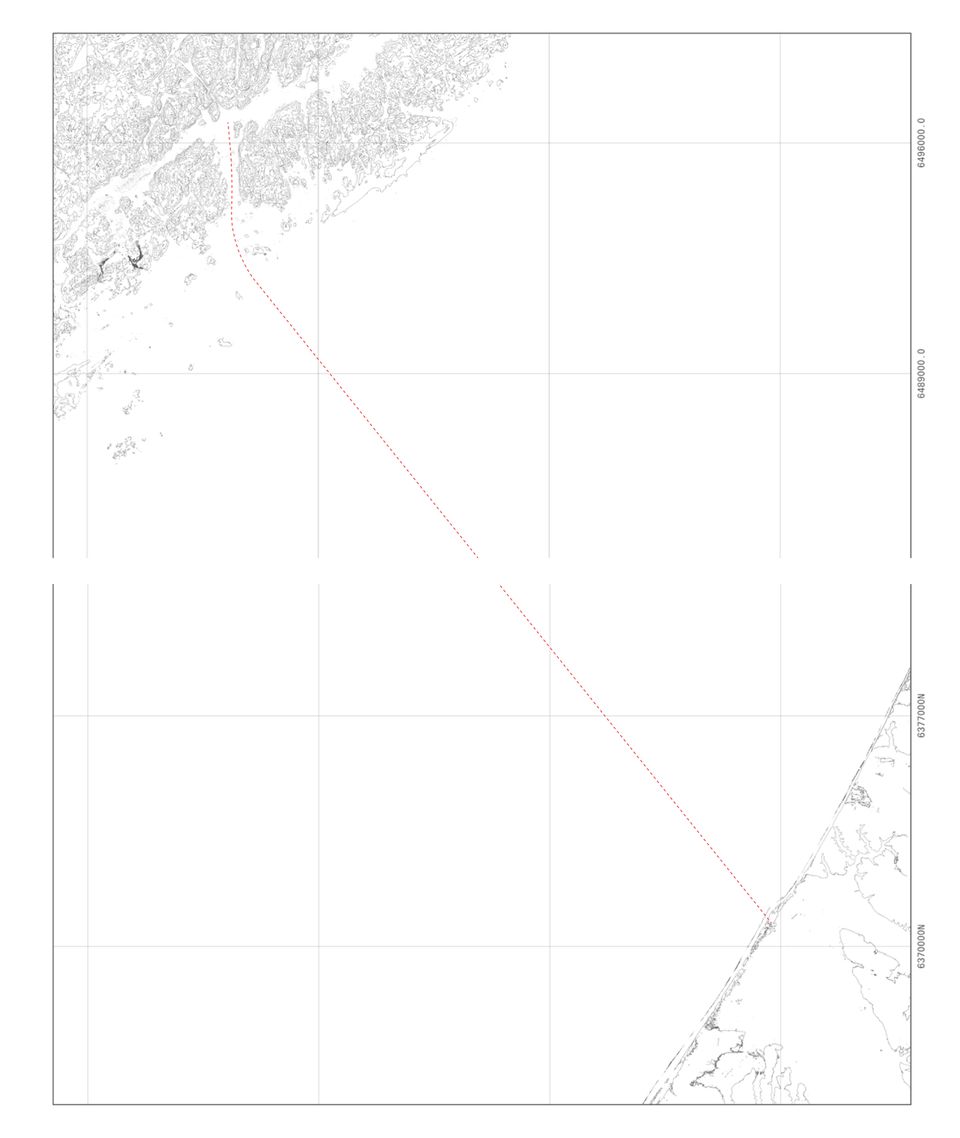

From 1867 until last year, there was a submarine cable connecting Arendal, Norway to Hjørring, Denmark. The cable, similar to a garden hose in diameter, crossed 130 kilometres to move data back and forth between the two regions—first as a telegraphic connector and eventually using fibre optic technology.1 I came to understand the connection between Arendal and Hjørring through this cable, but it did not establish contact; people, goods, and ideas have been traversing the line of this cable even before it was laid.

-

Map of Norway’s telegraph cables, 1867, The Mapping Authority (Norwegian Geographical Survey), Lithograph, 1:2000000. And “Submarine Cable Map,” accessed February 17, 2022, https://www.submarinecablemap.com/. ↩

At the scale of 1:10000, the cable is thirteen metres long. This is the distance that bricks, lumber, iron, granite, spices, boats, and butter travelled when frequent trade was established between the regions in the seventeenth century.1 These objects travelled at the territorial scale and formed an intimate relationship between the south of Norway and the north of Denmark in their wake. This history of trade means that today, there are stones and timber from Arendal in Hjørring and bricks from Hjørring in Arendal; it means that each place’s architectural monuments are built with the others’ materials. This territory—not bound by country borders, landmass, or language—was constructed through the constant circulation of people and things, commercial exchange, and family ties.2 The 130 km distance between Arendal and Hjørring collapsed by way of their mercantile relationship, resulting in a shared material culture that influenced architectural styles. The question here is not simply whether the cable represents a larger ecology of transported things, but to what extent these objects transformed the places they connected, and if reenacting this history has the potential to transform them once again.

Arendal—along with Amsterdam, Saint Petersburg, Copenhagen, and at least thirty-four other cities—has the moniker “Venice of the North.” The name refers to the modest canal system that once ran through the city, but also reflects an international approach to the place: Arendal as a simile of other places, Arendal from afar. Built upon seven small islands and protected from the open sea but accessible to large ships, Arendal was once a site of movement, flux, and exchange. It was significant for trade and at one point served as Norway’s single largest port (as measured by shipping tonnage).1 As Arendal grew in population and economy, processes of land reclamation led to the filling of canals and the extension of available property. Eventually, centralization and shifts in industry diminished Arendal’s role, both internationally and within Norway. Today, locals tell stories of a bygone era of international prominence somehow retained in the existing buildings: the church, a copy of one in Hamburg;2 the old town hall, ostensibly built upon sunken ships;3 a portal, designed by Italian architect Vincenzo Scamozzi, first translated into brick by a Danish architect, and then into timber by Norwegian builders;4 an old merchants house, built in the likeness of the town hall and containing antiques from Venice, Paris, and Singapore;5 lumber, exported from Arendal and upon which Amsterdam was built.6

The rise and fall of Arendal’s prominence might be read through the presence of submarine cables. Norway’s first international subsea cable was laid between Arendal and Hjørring, reflecting the region’s significance as a connection to continental Europe. By 1901, Arendal was Norway’s largest port and six out of Norway’s seven international subsea cables originated from there. Today, for the first time in over one hundred and fifty years, no submarine cables terminate in Arendal.

The short-lived prominence of Arendal is also remembered through artistic depictions. An eleven-metre-wide 1957 fresco by Axel Revold—a notable twentieth-century Norwegian painter—illustrates side-by-side port scenes of Cairo, New York, London, and Arendal, signalling the perception of Arendal as an international actor. But in numbers, Arendal, with a population of 16,080 in 1890, never compared to Cairo (population 570,062 in 1890), New York City (1,515,201 in 1890), or London (4,231,431 in 1890).7 Still, Arendal did play a role in trade at this scale: with five hundred ships registered in 1877, it was the largest maritime city in the Nordic Region.8 Additionally, prior to 1807, the region took part in the nefarious triangular trade between Europe, West Africa, and the Americas—as evidenced by the 1768 wreck of slave ship Fredensborg outside of Arendal, which had carried 235 enslaved West Africans from the Republic of Ghana (formerly The Gold Coast) to St. Croix in the Caribbean.9 Although their participation in the international slave trade has often been diminished, it is important to note that their involvement gained them a privileged position when it came to mercantile relations. Arendal had a remarkably large reputation abroad and it was because of the town’s access to the international market that towns along the western coast of Denmark were formed.

-

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Arendal,” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 11, 2013, https://www.britannica.com/place/Arendal. ↩

-

Johan Christian Frøstrup, Arendal Byleksikon (Arendal: Friluftsforl, 2017), 310. ↩

-

Bjørn Barexstein, conversation with author, November 15, 2020. ↩

-

“Historien om Arendal gamle rådhus,” Arendal Kommune, accessed February 17, 2022, https://www.arendal.kommune.no/tjenester/kultur-idrett-og-fritid/museer-og-kulturhistorie/historien-om-arendal-gamle-radhus/. ↩

-

Ulrik Sissener Kirkedam, Kolbjørnsvik 1711 -2011 En 300-Årig Historie Om Tettstedet Kolbjørnsvik (Hisøy Historielag, 2011), 86-88. ↩

-

Elisabeth Kallevig and Norsk Sjøfartsmuseum, Sjøfarten I Arendal 1815-1850. Vol. Nr. 29. Skrift [Norsk Sjøfartsmuseum : Trykt Utg.], (Oslo: Norsk Sjøfartsmuseum, 1939), 29. ↩

-

“Cairo (Egypt),” Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol. 4 (11th ed.), (Cambridge: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1910), 953–957; John S. Rep Billings, Vital Statistics—New York City and Brooklyn (Department of the Interior, US Census Office, 1894); J.G. Bartholomew, The Pocket Atlas and Guide to London (London: John Walker & Co, 1899). ↩

-

Arendal Kommune, Historien Vår, https://www.arendal.kommune.no/tjenester/kultur-idrett-og-fritid/museer-og-kulturhistorie/historiske-artikler/historien-var/. ↩

-

More information on Norway’s involvement in the triangular trade can be found in Roar Løken, De Dansk-Norske Tropekoloniene: Sukker, Krydder, Slaver Og Misjon (Denmark: Solum Bokvennen, Vidarforlaget, 2020). More information on Fredensborg can be found at “Fredensborgs Siste Reise – Dokumentene Forteller,” KUBEN, https://www.kubenarendal.no/publikasjoner/fredensborgs-siste-reise/. ↩

Along this western coast lies Hjørring, a Danish municipality defined by a flat, grassy landscape with dramatic dunes. Its towns such as Løkken and Lønstrup, formed and funded by their proximity to Southern Norway, originally functioned as charging stations for merchants trading between Denmark, England, and Norway.1 For these towns, orientation toward Arendal was essential. Iron, granite, lumber, boats, spices, sugar, and tobacco were frequently sent to Hjørring from Arendal. In exchange, boats returned to Arendal with grains, butter, and meat from Hjørring.2 Unlike Southern Norway, the north of Denmark had few material resources at hand, but locally-produced brick constituted a large part of the building mass and was likely the only material export from the region—at its peak, Hjørring had at least 103 brickworks.3

In 1851, Løkken developed a rescue service that would aid capsized boats and their crews. Many large ships coming from Southern Norway wrecked along the coast and, once helped ashore, were retained for cargo and parts. An 1888 advertisement for the auctioning of salvaged goods reads:

-

Rosenvinge, “Nabohandel Over Skagerrak.” ↩

-

Rosenvinge, “Nabohandel Over Skagerrak.” ↩

-

Tommy Nilsson, Teglværker i Danmark, Jernbanen Danmark, https://www.jernbanen.dk/artikler.php?artno=63. ↩

“Auction in Løkken: Tuesday, 7. May. Lunch at 12:00. The wreck from Arendal’s Alpha: wooden beams, dry wooden planks (6-8 cubits long), 20 trees (10 cubits long), 10 new window sills, 1 mast (25 cubits long), iron chains, iron brackets, boards of various dimensions, salted pork meat, grains, and potatoes.”1

-

Vendsyssel Tidende 26, November, 1888, as cited in Hans Fink, “Strandingsberetninger 1880-1900,” Løkken Lokalhistoriske Arkiv, http://loekkenhistorie.dk/redningsvaesenet/314-strandingsberetninger-1880-1900. ↩

These shipwrecks provided a source of income and materials for the people of Løkken outside of more typical forms of commerce. Pieces from wrecks became components in nearby buildings, with their unique provenance adding to the material history in the region. The trading of goods also necessitated the storage of things, which lead to structures built at a scale seemingly unrelated to the population. Large warehouses used to store goods for distribution were built in Løkken, even when the town only had a dozen houses. The town had to adapt to the flow of materials that were collected and then exported, imported and then distributed.

Despite their mutual relations, ties between Southern Norway and North Denmark diminished as material sourcing and influence became simultaneously more international and more nationally centralized. When looking at circulation trends on the site, during both times of heightened and diminished exchange, Arendal emerges primarily as a place of export and subtraction and Hjørring as a place of import and accumulation. This tendency continued even beyond the era of co-dependence when coastal erosion in Hjørring during the twentieth century required materials from Norway to bolster the shoreline. A formalized plan for coastal protection can be traced back to 1917, but after two houses fell into the sea in 1967, protection of the coast became a priority. In 1976, a large storm took five metres off the Danish coast in a single night, resulting in the construction of massive breakwaters made of Norwegian granite in 1983.1

While the proximity, ease of transport, and complementary resources between Arendal and Hjørring constitute a natural locality, globalized supply chains have disintegrated the necessity for either of the towns. Today, Arendal has little trade or industry left and Hjørring relies almost exclusively on tourism for subsistence.

-

National Rivers Authority, National Rivers Authority September 1991 Visit to Danish Coastal Authority (Bristol, England: National Rivers Authority, 1991), http://www.environmentdata.org/archive/ealit:2838. ↩

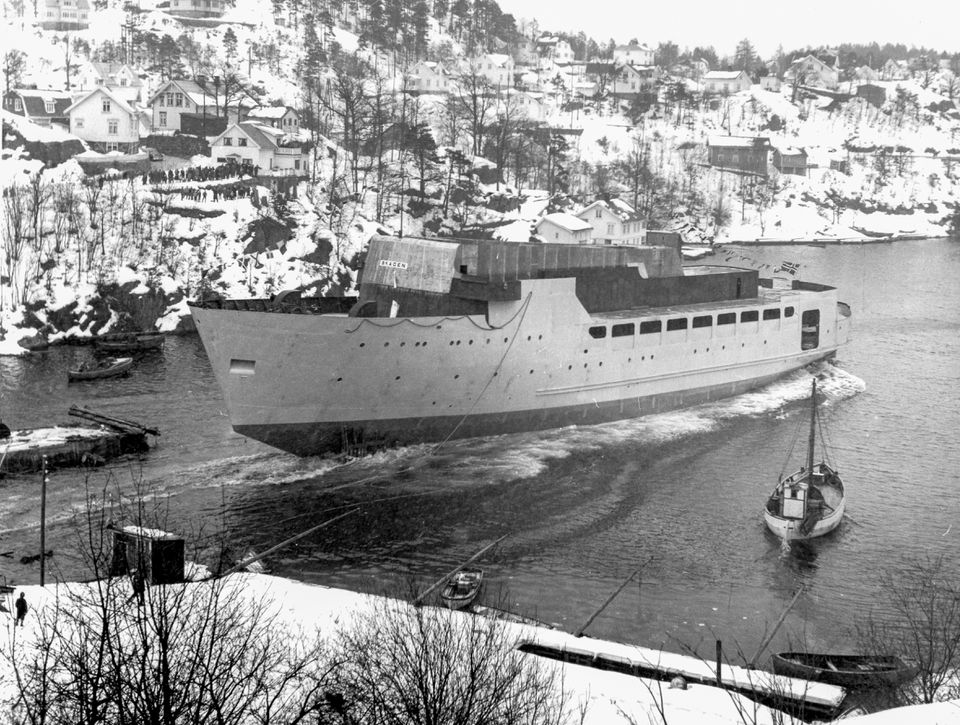

From 1958 to 1975, M/S Skagen—a passenger, car, and rail ferry—traced the same route as the cable, briefly re-establishing the exchange between Arendal and Hjørring by creating continuous rail lines between North Denmark and Southern Norway and increasing movement between the regions. The ship was constructed in Arendal at the boatbuilder, Pusnes Mekaniske Verksted; the boat’s launch was a well-attended event with people lining the city’s coast to watch the performance of its first sail. The ship ferried trains, cars, and vacationers in search of cheap beer and sandy beaches until 1975 when it was sold to Fred. Olsen Oceanics A/S and converted into a diving ship for oil exploration in the North Sea. In 1988, the boat was sold and rebuilt again to be used as a fishing supply ship in the Arctic, only to be detained in 2007 due to payment problems. After sitting at the Drammen shipyard for twelve years, M/S Skagen was sold to a Russian company and exported to Lithuania for demolition.

Beyond its own trajectory, the lifespan of M/S Skagen also illustrates a trend in Arendal: exciting origins leading to quiet demolitions. In Arendal, the white wooden houses are protected, leaving little room for new development. These buildings are now stuck—held together by cement, thick layers of paint, and the policies that prevent their movement. With the wooden houses secured, twentieth-century buildings are demolished for the sake of development. Structures once celebrated, adorning the fronts of postcards and embellishing the image of Arendal, are now levelled. The demolition is an exhibition, visible from every point in the city.

Buildings are glued, screwed, bolted, welded, and regulated—but buildings are not permanent, nor resolved upon construction. Materials come together to provide structure for designated purposes; resources and labour are put into processing, transporting, and erecting those materials and when the lifespan of their use reaches its end, more resources are put into dismantling and redistributing the rubbish. Often considered as fixed and site-specific entities, completed works of architecture resist modular thinking. But this perspective limits our understanding of both historical context and future potential.

Considering Arendal and Hjørring, disparate places constructed through flux and exchange, as figurations of what was once a 130-kilometre-long local condition allows us to reengage with them as a site of potential. Today, the systems that govern the sides separate them further—developments and regulations happen at different times, come from different authorities, and have different motives and budgets. In contemporary documents about the sites, Arendal is considered in relation to Oslo and Hjørring in relation to Copenhagen. As an alternative, we might look to Arendal from Hjørring and to Hjørring from Arendal—allowing each one to permeate the other through scale, use, and materials.

A moving material forms a direct connection between its place of origin and its place of arrival. To understand this we must accept that, as Arjun Appadurai writes, objects “carry the force of their histories, their journeys, the accidents and adventures that befall them and these often show up in their shape, form and force.”1 One must only look to the local history websites, Facebook groups, and newspaper articles of Arendal and Hjørring to see the weight that these material histories carry. We can thus consider the intimacy of this longstanding international connection and the collapsing of distance through material exchange. The history of this site is one of subtraction and accumulation; perhaps a reenaction of this history can provide value for disused architectural components and reorient each side toward the other.

-

Arjun Appadurai, “Museum Objects as Accidental Refugees,” in Migration—the journey of objects, ed. Johan Deurell (Röhsska Museum of Design and Craft, 2021), 75. ↩

Before we build, something must be unbuilt: a site scraped, landscape levelled, building demolished. Most architectural drawings describe construction with new materials and contain the schedule beginning when the site has been prepared, but this starting point is really a middle—the actual building begins at the unbuilding, it begins at scraping not just of the building site, but sites around the world: excavating the rocks for foundation, digging and baking the clay for bricks, transporting materials, importing expertise. Through these processes, architecture tangibly connects disparate places and times. In Arendal and Hjørring, material histories are fundamental—enthused locals know the story of each building and the history of each material. People relate to the provenance of their buildings—both the origin stories and the tales of their demise.

There is potential for migrating materials to erode the distance between places. I wonder about the effect of a concrete column, migrating from Arendal to Hjørring. Do locals watch the arrival of the parts and the spectacle of the construction? Fifty years on, do they mention that the structure comes from Arendal? I think they might.