Promise or Perturbation

Five Field Notes from the Canadian Roadside by Paul Nadeau and Laura Pannekoek

The town of Clinton, British Columbia—a small town, with no airport or train station—was originally developed as part of the Cariboo Gold Rush Trail. Though it now subsists on revenues from local gravel production, cattle ranching, and tourism, the town is littered with Gold Rush iconography: Old West-style facades, homesteader puppets, and antique shops full of rusty pans and pickaxes line its one main road. There is also a weathered Shell sign, detached from any gas station, an emblem of the petrocultural optimism that succeeded Clinton’s once manic desire for gold. Extractive projects and the cultural sentiments that come with them are layered in Clinton, and the town’s roadside signs show it. What is the function of the roadside sign in the understanding and interpretation of a place? Signs like those in the image above host layers of settler colonial narratives about extraction and variously dwindling or thriving beliefs in the economic promise of that extraction.

Here are five field notes taken from a road trip we took in July 2021 from Montréal to Victoria that describe encounters with roadside signs, those public-facing documents that mark territory semiotically and topographically at the same time. Some of the signs in this collection are evidence of a persistent settler-extractive orientation to place, one that more often than not is funneled through a set of affective connections to a real or imagined history. These conflict with other signs that, for instance, emphasize Indigenous subsistence practices. Still other signs attempt to reconcile these pasts and presents in new imaginaries of places designed for tourism. By figuring roadside signs as territorial devices, we examine some ways territories are made and unmade in the context of settler-extractive practices in rural Canada.

Prince Rupert is a western seaport on the scale of Vancouver’s where timber, grain, coal, and more move through the terminals. Getting here by land requires an uninterrupted 150-kilometre drive from Terrace, BC, on Highway 16, between railway coal cars on one side and the Skeena River on the other. It takes a long time: this is where the road ends and where, a sign tells us, “Canada’s wilderness begins.”

The sign on the left is cracked, worn by layers of salt and sun: wetting, drying, cracking, and bleaching. Figuring prominently are a fisherman and a cannery worker who, respectively, hold the caught salmon and the canned salmon, the raw material and the packaged commodity. The sign presents the Canadian wilderness as a challenge, an invitation to catch, kill, and can. The economic potential of the ocean was realized through the process of canning. Canning is the material process of the ontological transformation from living creature to commodity: non-perishable, transportable, exportable. The canneries of Prince Rupert were a transformational terminal for Pacific salmon: they turned living creatures into non-perishable and transportable products.1 That was then, before the years of sea spray. Now, Pacific salmon populations are in severe decline.

Today’s Prince Rupert has adventure tours, a nearby sign tells us. Grizzly bears, killer whales, and humpbacks await, striking fear and wonder. If Prince Rupert’s economy in the twentieth century centered on fishing and canning—packaging and exporting the wild—its twenty-first century is about selling the spectacle of wilderness in a controlled environment on site.2 Adventure tourism takes advantage of the settler-colonial desire to venture into and take control of unknown places.

This pair of signs tell a story of the western coastal economy’s remaking. The resource frontier of the Pacific—a territory defined by the health and numbers of sea life populations—is itself repackaged into saleable tracts of touristic experience. Made rare by overfishing, sea life is made newly valuable through scarcity. The depleted ocean is revalued as social capital, captured by tourists in the experience of seeing a whale in the wild.

-

Jeff Diamanti defines a “terminal” as something that “marks the physical and logical end of one thing and the initiation of another, and the abstraction connecting the two sides of the terminal (what it ends and what it sources).” See Jeff Diamanti, Climate and Capital in the Age of Petroleum: Locating Terminal Landscapes, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021). ↩

-

See Robert Fletcher, Romancing the Wild: Cultural Dimensions of Ecotourism, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 113–129. ↩

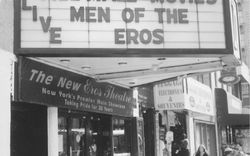

“World’s largest” is a much-repeated claim to fame in the genre of roadside attractions. The superlative asks its passersby to stop, saying: this is not a drive-through town, but a place with a claim to history. Cobalt, Ontario, is such a place, or so its claim post imagines it to be. A boom in the early twentieth century made Cobalt the epicenter of innovation in hard-rock-mining technology. The investment structures that large-scale mining projects require helped build the Ontario banking industry and the Toronto Stock Exchange. A bust quickly followed, and then another boom in the 1950s. Now, Cobalt has become a tourist destination. “Cobalt is a dynamic community nestled in the heart of the Pre-Cambrian Shield,” says the official town website. The local colour that Cobalt wants to promote is so tied up with mining that its very location is understood geologically (vertically) rather than topographically (horizontally).

The claim post is a landmark in its plainest meaning: it is a marker of land, where land is understood as property. It is settler colonial infrastructure staking a claim that underlies settler colonial discourse, ideology, and jurisdiction. As an architectural device, the post performs the active construction of a property relation and boundary-making. But its materiality is curious. All you need for a claim is a sign, but this is a post made from a tree. If staking the claim was all the claimant was after, why did this tree need to be cut down before being put back in the ground? Something changes during the process of chopping down a tree only to erect it again as a signifier of ownership. A transformation occurs, from ecology to property, from land to territory, from wood to performance of power.

What is the claim post’s function now? Cobalt is no longer a prospecting frontier but a commodification of that frontier identity. Its claim post is a monument to ideas about land and ownership that came at the expense of, and by committing acts of violence on, Indigenous peoples and ecologies. Cobalt’s turn from mining to tourism changes nothing about the settler colonial logic and sentiments that prompted the town’s founding and propelled its boom in the early twentieth century. The town’s roadside claim post testifies to the ongoing settler ideology that persists in Canada even as local and national economies change shape.

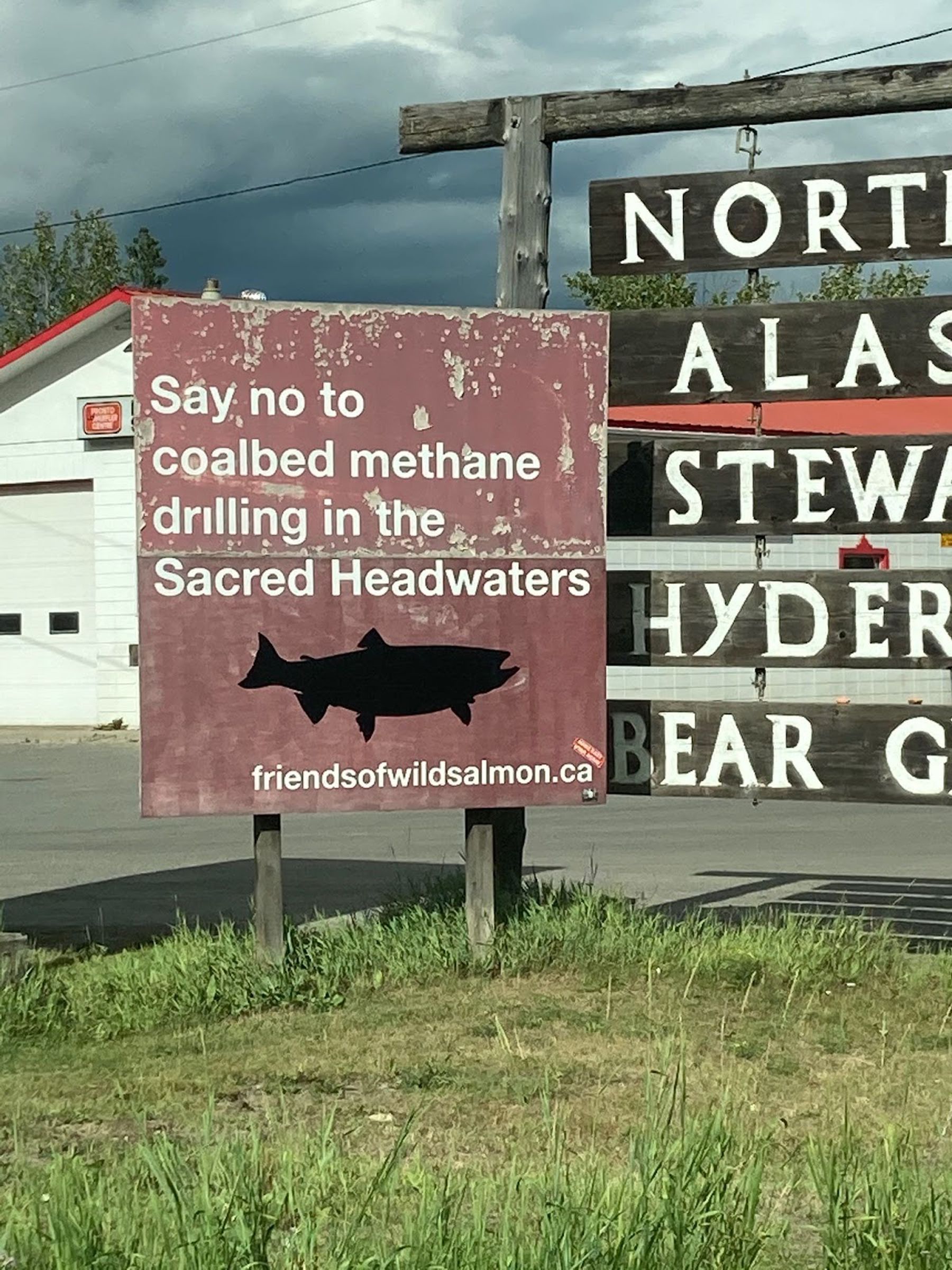

The intersection of Highway 16 and the Alaska Highway is a junction in more ways than one. A call to “say no to coalbed methane drilling in the Sacred Headwaters” collides with the highway sign, partially obscuring it. Still, neither Alaska nor the Sacred Headwaters are anywhere near this spot; distances and concerns are collapsed, condensed, and focused at this intersection. The junction marks contested ground that demands attention. Neither sign can be considered without the other.

The coalbed methane sign is a few years old: the plywood surface the sign of is visible through chipped paint. That there are friends of wild salmon suggests the recognition of a symbiotic relationship. You keep reproducing and being caught, and we make sure your rivers and oceans are livable. But this “we” is particular. The Skeena, Nass, and Stikine Rivers all flow from the Sacred Headwaters in a watershed that is of critical importance to the Tahltan Nation.1 Being so close to where Wet’suwet’en land defenders continue to block the Coastal Gaslink pipeline, we stop to consider, thinking with Anne Spice, that perhaps this is what “critical infrastructure” really means: not just pipelines and refineries but the ecologies and lifeforms that sustain lives, livelihoods, and ways of living.2 The argument against drilling is the Indigenous right to fish and to live. In this case, drilling has stopped, and protections have been put in place.3 Does this victory mean it is time to take the sign down? Or should it be left up as a reminder that this site marks contested ground?

-

Ministry of Forest, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, Tahltan Nation, “Protecting the Sacred Headwaters of the Klappan Valley,” press release, 27 August 2019, https://tahltan.org/press-release-protecting-the-sacred-headwaters-of-the-klappan-valley/. ↩

-

Anne Spice, “Fighting Invasive Infrastructure: Indigenous Relations against Pipelines,” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 9 (2018): 40–56. ↩

-

“Oil, Gas Development Banned in B.C.’s Sacred Headwaters,” CBC News, 18 December 2012, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/oil-gas- development-banned-in-b-c-s-sacred-headwaters-1.1283417. ↩

At the Coastal GasLink terminus in Kitimat, LNG Canada is building a massive export terminal for liquid natural gas mined in northern BC. The pipeline connecting the port to the gas fields continues to be contested and blocked by Wet’suwet’en land defenders. Kitimat, like Prince Rupert, has remarkably deep water close to shore, making it especially suitable for deep-sea shipping terminals: it is for this reason that this site at the head of the Douglas Channel, on Haisla Nation land, has been singled out since the 1950s for several energy-related projects, among them a sawmill, several natural gas pipelines, and export facilities.

The aluminum company Alcan’s construction of a smelter, a dam, and the town of Kitimat, referred to simply as the “project,” was once Canada’s largest infrastructure plan; the development was intended to spawn a city of 50,000 people.1 Seventy years of boom and bust have taken their toll; the city never grew to size. During the construction of the smelter and dam project in the 1950s, 8,000 jobs were promised; less than half materialized. The new LNG terminal is, however, a revival of that optimism. In the morning at our camp spot by the river, a man pulled up in a truck, maybe to look at the river, maybe to fish. He told us he used to work at the smelter. Came to Kitimat in the 1960s and never left. He talked about the LNG terminal. “They’re building temporary housing for 8000 workers. That’s the population of the town.”

Along the western shore of the bay is Alcan Road, named after the company it services. We drove it until we reached this scene at Hospital Beach, which offers a view of the aluminum smelter and the Coastal GasLink export facility under construction. In front, a weathered sign, both informative and desperate: “please take care of this resource.” Thinking with Diamanti again, we think about this landscape as terminus, where things are transformed into other things, where materials leave behind one physical context and enter the abstract world of logistics before being transformed again at another terminal far from this one. Please take care of the shoreline habitat as its cycles of boom and bust run up against the liminality of the terminus. Please let the extractive regime finally run up against some kind of end, some kind of terminus to the purgatory between decline and promise.

-

Walter Thorne, “Kitimat: A Century of Boom and Bust,” The Northern Sentinel, 1 December 2018. ↩