Capital in Motion and the Reproduction of Empire

Sebastián López Cardozo on the territorial fixations of capital. Illustrations by Cécile Ngọc Sương Perdu

“Although [buildings] have the materiality of cement, brick, and concrete—and are implanted in cities, transforming their landscape and ways of functioning—these objects are, at the same time, abstractions, fractions of units of value circulating in the financial sphere.”

— Raquel Rolnik, Urban Warfare, 57.

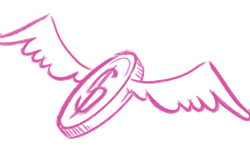

“Blest paper-credit! last and best supply!

That lends Corruption lighter wings to fly!

Gold imp’d by thee, can compass hardest things,

Can pocket States, can fetch or carry Kings.”

— Alexander Pope, “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” 90n.

Dematerialization of Money Forms

In “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” Alexander Pope (1688–1744) tells the story of an “unsuspected old Patriot” who, having received a bag of guineas from the king as a bribe, begins to silently make his way out of the castle.1 The bag bursts open from the weight of the coins, and a “dropping guinea” speaks, “[jingling] down the back-stairs,” betraying the corrupt dealings of the old man and his king.2 In this epistle, composed around 1730, Pope compares the “speech” of the metallic coin—its sonoric material manifestation—to the stealth and silence of paper credit, a form of currency only recently introduced in England.3 This new form of money, fitted with “lighter wings to fly,” could “[sell] a king, or [buy] a queen,” unseen and silent.4

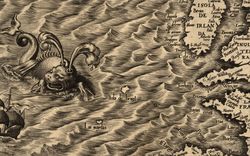

Metallic money—coins minted of precious metals—had already offered a compact and less-cumbersome means of exchange compared, for example, to forms of proto-money like the squares of fur used as currency in Russia under Peter the Great (1682–1725).5 But heavy metallic money too, notes historian Fernand Braudel, had its “mechanical problems.”6 In eighteenth-century Naples, for example, the value of all copper, silver, and gold coins in circulation equaled 18 million ducats, while the total outstanding payments owed among all parties amounted to a value of 144 million ducats.7 This worked only through constant circulation: “Each coin must change hands eight times.”8 If, as Karl Marx wrote, capital is value in motion,9 then the weight and materiality of metallic money would soon render this form of currency “slow to fulfill its functions,” and would have to be “pushed forward or somehow replaced.”10

Colonization of the Americas by European empires propped up the predominance of metallic currency in Europe and relieved the circulation pressure on the monetary supply. And yet, the vast expansion in the volume of trade that ensued—with the formation and development of capitalism—propelled a shift away from precious metals and toward lighter and less material forms of money (like the secured, private banknote).11 Anthropologist Shannon Speed (Chickasaw) writes that “European settler colonialism was the catalyst of capitalism’s expansion and continues [italics added] to structure life under capitalism as it moves through different phases.”12

-

Alexander Pope, “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” in Epistles to Several Persons (Moral Essays), ed. F. W. Bateson (London: Methuen, 1951), 90. “Epistle III” was first written in 1732 and the volume was published in 1781 as Moral Essays: In Four Epistles to Several Persons. For the connection between money, speech, and the epistles of Pope, see James Engell, The Committed Word: Literature and Public Values (Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999). Two additional sources, referenced in Engell’s book, are valuable to our understanding of the materiality of money and Pope’s work: the “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst” cited above, and Fernand Braudel, Capitalism and Material Life 1400–1800, trans. Miriam Kochan (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1967). ↩

-

Pope, “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” 90. ↩

-

Engell, The Committed Word, 103. ↩

-

Pope, “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” 91. ↩

-

Braudel, Capitalism and Material Life 1400–1800, 332. ↩

-

Braudel, 362. ↩

-

Braudel, 355. ↩

-

Braudel, 335. ↩

-

For an introduction to the ideas of Karl Marx and their contextualization for today, see David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); David Harvey, Marx, Capital, and the Madness of Economic Reason (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩

-

Braudel, Capitalism and Material Life 1400–1800, 362. ↩

-

“Silver shipped to Spain [from new colonial dominions] in little more than a century and a half exceeded three times the European reserves.” Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973), 33. See also, Bank of Canada, “A History of the Canadian Dollar: New France (ca. 1600–1770),” https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/1600-1770.pdf,” 2–3; and Braudel, Capitalism and Material Life 1400–1800, 364.” ↩

-

Shannon Speed, “Structures of Settler Capitalism in Abya Yala,” American Quarterly 69, no. 4 (2017): 788. ↩

Airborne Money and Its Spatial Fixes

In Pope’s time, money was fitted with wings metaphorically: gold, with the added wings of a lighter currency like paper credit, can accomplish the “hardest things”; a single paper leaf can “waft an Army o’er or ship off Senates to a distant Shore.”1 However, the winged money of Pope’s time still relied on slow circulation infrastructure; wafting “an Army o’er” would have been heavy and cumbersome. In our own time, the poetics of “airborne” money (a term used by urban planner and housing expert Raquel Rolnik) feel far less metaphorical: with the aid of circulation infrastructure based on instantaneous telecommunication, value can circle the globe in less than a second.2

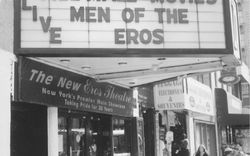

As currency becomes increasingly less physical and more abstract (from fur to gold coins to paper to air) its so-called value takes on an increasingly geographic dimension. Under capitalism, money constantly requires new frontiers for expansion, or places to land (Rolnik’s formulation)—what economic geographer David Harvey has termed capitalism’s spatial fixes.3 These are, quite simply, the places where money seeks to reproduce itself. The concept is derived in part from the English definition of the term “fix,” meaning (1) fastening or securing something to a place, and (2) repairing something.4 The second definition, Harvey explains, also has a metaphorical derivative, commonly used to describe something needed to satisfy an addiction (i.e. getting one’s fix).5 This typically provides a temporary repair, and it soon requires further fixes. It is with these definitions in mind that Harvey used the concept of the spatial fix to describe capitalism’s addiction to fixing its “inner crisis tendencies” by “geographical expansion and geographical restructuring.”6

In an open, territorial expansion (akin to Harvey’s geographical expansion), spatial fixes register as new claims in the unconquered wilderness—what architect Lars Lerup describes as a “struggle of economics against nature”7—moving outward radially from a central point and from air to land. When the system becomes closed (akin to Harvey’s geographical restructuring), the new frontiers must necessarily be generated from within existing territory, following a cyclical pattern of blight and renewal—a contrived obsolescence that serves only the needs of capital itself. “[Capital] has to build a fixed space (or ‘landscape’) necessary for its own functioning at a certain point in its history,” writes Harvey, “only to have to destroy that space (and devalue much of the capital invested therein) at a later point in order to make way for a new ‘spatial fix.’”8

-

Pope, “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” 91. ↩

-

Raquel Rolnik, Urban Warfare: Housing Under the Empire of Finance, trans. Gabriel Hirschhorn (London: Verso Books, 2019). In Urban Warfare, where the metaphor of “airborne” money is deployed, Rolnik contextualizes Harvey’s notion of the “spatial fix” in relation to what she witnessed, among other things, during her time as United Nations Special Rapporteur after the Great Recession of 2008. ↩

-

See for example: David Harvey, “Globalization and the ‘Spatial Fix’,” Geographische Revue 2 (2001). ↩

-

Harvey, “Globalization and the ‘Spatial Fix’,” 24. ↩

-

Harvey, 24. ↩

-

Harvey, 24. ↩

-

For more on Lars Lerup’s formulation of “the struggle of economics against nature,” see Lars Lerup, “Stim & Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis,” Assemblage 25, no. 25 (1994). The terms Stim and Dross (Stim as “economics” and Dross as “nature”), which Lerup developed to describe Houston, Texas, in the 1990s, were useful in visualizing money flows and their effect on territory. The Stim, in its literal translation a “stimulation” or a “voice” (compare to Pope’s money as “speech”), defines itself against an outside (the Dross) that is not its opposite but its very own absence—the absence of money flows. Lerup defines Dross as the “ignored, undervalued and unfortunate economic residues of the metropolitan machine.” ↩

-

Harvey, “Globalization and the ‘Spatial Fix’,” 25. ↩

Creation breeds destruction; economy consumes nature. The machine becomes the garden. Vestigial organs thicken and bloat. The new gods claim their space, sterilizing territory and numbering parcels. The undigested chaff collects in the corners. Bodies labour amid fragments of broken nature to erect the next colossus…

As Rolnik notes, in recent decades, the volume of airborne money has exceeded (as a result of hyper-accumulation) the number of places where capital can get its fix: “This ‘wall of money’ increasingly [seeks] new fields of application, transforming whole sectors (such as commodities, education financing and healthcare) into assets to feed the hunger for new vectors of profitable investment.”1 When this process takes place—the priming of a sector for the landing of capital—the objects and landscapes it affects live in two primary states simultaneously: The first is their physical state that we are all familiar with (for example, “[their] materiality of cement, brick and concrete”); the second their abstracted value (“fractions of units of value circulating in the financial sphere”).2 In other words, objects and territories are both their presence and the impact on the lives they help to shape. They are also monetary flows plugged into global financial networks. Increasingly, this is where (and how) money lives.

Unlike the jingling coins of the old Patriot, the monetary flows that build objects and territories today are silent, invisible. They move in every direction, jumping from air to land and from land to air. Today’s money rarely speaks through literal jingling. It speaks both with the way it writes—and resides in—territories (sprouting high-rises, highways, and oil wells) and the way it unwrites them (waging wars on vulnerable bodies and lands). As Pope predicted, “a leaf, like sybils, scatter to and fro Our fates and fortunes, as the winds shall blow; Pregnant with thousands flits the scrap unseen, And silent sells a king, or buys a queen.”1 Money speaks at once through the construction crane and the wrecking ball.

-

Pope, “Epistle III: To Allen Lord Bathurst,” 91. ↩

…Against the fury of combustion and consumption, nature-in-struggle (the vast outside) and its orphaned bodies move and sing in revolt. Against the mechanized cacophony, our nature calls to itself and recalls the strength and reach of its voice. The streets swell with gatherings, the body remembers itself. The hot air vibrates with story and song. In the convergence, place and time collapse to reveal shared air, shared land, shared futurity. The vast outside knows its continuity.

This piece was conceived of in collaboration with Sumayya Vally. The author is grateful to Lauren Phillips, Gabriela Palomo, and Stefan Novakovic for their contributions and feedback.