Fictions of Fictions

Piper Bernbaum on the material facts and urban fictions of the Eruv wars in Jerusalem

It is Shabbat. I have arrived on Jaffa Street in Jerusalem, having taken the sherut (city-to-city mini-bus) from Tel Aviv, and am now waiting for a ride to the nearby neighbourhood of Kiryat Yovel for a self-directed walking tour. The streets are empty, no stores are open, and scarcely anyone is out and about. Even the famous Mahane Yehuda market is closed; the delicious smells and vibrant music that usually permeate its alleys and market are nonexistent. The Sabbath has a serious influence on the city. It is a day of observance and prayer based on a unique set of religious laws. Jerusalem holds to this contract of observance; on Shabbat, the religious day of rest, the city is at its most sacred.1

I had come to Jerusalem to observe its Eruv and to learn more about the fraught history of Eruv wars in the city.

-

Shabbat (Hebrew), Shabbos (Yiddish) and the Sabbath (English) are interchangeable terms in the Jewish faith to commemorate God’s creation of the heavens and the earth in six days with a day of rest on the seventh day of the week. Shabbat is a day of rest from work and business observed every week beginning at sunset on Friday evening until sunset on Saturday evening. Observance of Shabbat is the fourth of the Ten Commandments given to the Israelites by God after their exodus from Egypt. ↩

The maintained Eruv line around the small community of Beit Me’ir running through the landscape surrounding the hillside neighbourhood, 2023. Photograph by Piper Bernbaum

The Eruv is a spatial boundary drawn by a wire stretching across the city to create a symbolic, private domain. Its function is to allow for leniencies in public space that otherwise would only be permitted by Sabbath law within the home or private sphere. The type of justification is a legal fiction: an assertion accepted as true, however likely fictional.1 As a loophole, the Eruv finds ways around legal structures in place both in Jewish Law and in civic legislation. It is a physical and spiritual practice that encloses parts of the city to establish a privatized domain (such as a house or a synagogue), but it is entirely permeable and often goes unnoticed by the everyday citizen. As cities evolved and technologies modernized, the Eruv was established to help Jews work around the contract of religious devotion and still follow the Sabbath rules. One of the Ten Commandments stipulates maintaining the Sabbath as a holy day of rest—no work can be undertaken on this day. The Eruv shapes a territory that makes space for more people to be active members of the city and creates a pluralistic public domain within the complex context of urban centres.

-

Marcus Jastrow, Sefer Ha-milim: Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Bavli, Talmud Yerushalmi, and Midrashic Literature (New York: Judaica Treasury, 2004), 1075. ↩

I fell in love with the Eruv in North America. I bounced between Manhattan and Brooklyn, Boston and Buffalo, Toronto, and Montreal, to experience the Eruv, a beautiful, light artifact that painted a picture of survival, maintenance, self-determination, care, community, respect, tolerance, and simplicity. Every wire I encountered told me a story of a community, their needs, and the way they had lovingly cared for the everydayness of their city. The exchanges and negotiations the Eruv activates between a community and its city model possibilities for a pluralistic and supportive world. Ultimately, the Eruv creates a space of tolerance, and I happily get caught up in the urban optimism it represents. Yet as my mind returns to the bench I sit upon on Jaffa Street, I begin to realize that the Eruv is entirely different in Jerusalem.

For some time, I had wondered if all of Israel could be considered an Eruv. Its borders are fortified by the Mediterranean Sea on one side and border crossings, walls, gates, and patrolled checkpoints around the rest. In a map of Jerusalem I found reading through artist Sophie Calle’s book L’Erouv de Jérusalem, a line depicted a winding, massive boundary that traced the city’s rolling hills.1 It made sense to me that a devout city would want an all-encompassing Eruv to encircle most neighbourhoods for the benefit of its religious residents. Eruvin are always understated and purposely difficult to find. They blend into their contexts and surroundings and often develop out of already existing infrastructure. But, after years seeking out these boundaries, I now know what to look for to spot their subtleties. However, when I arrived in Jerusalem, I encountered pieces and components of the Eruv that lead to dead ends and unfinished boundaries. I had to pay attention to find the traces of Eruvin in Jerusalem since I could not trace their limits. Here, Eruvin were haphazardly built, oddly located, and often incomplete, and they certainly did not define a kosher (enclosed) religious space. Fishing wire blows in the wind and tethers to posts and fences, its open and broken edges creating fragmented boundaries along highways and streets—remnants of the Eruv, or something that resembled it. For most, such traces of the Eruv are unnoticeable, but for me, it was strange to see something that had seemed to be so sacred and rare as so abundant, abandoned, and mostly dysfunctional.

-

Sophie Calle, L’Erouv de Jérusalem (Arles: Actes Sud, 2002). ↩

Checking the Eruv line wires on the streets of Jerusalem to ensure they are intact and complete, 2023. Photograph by Piper Bernbaum

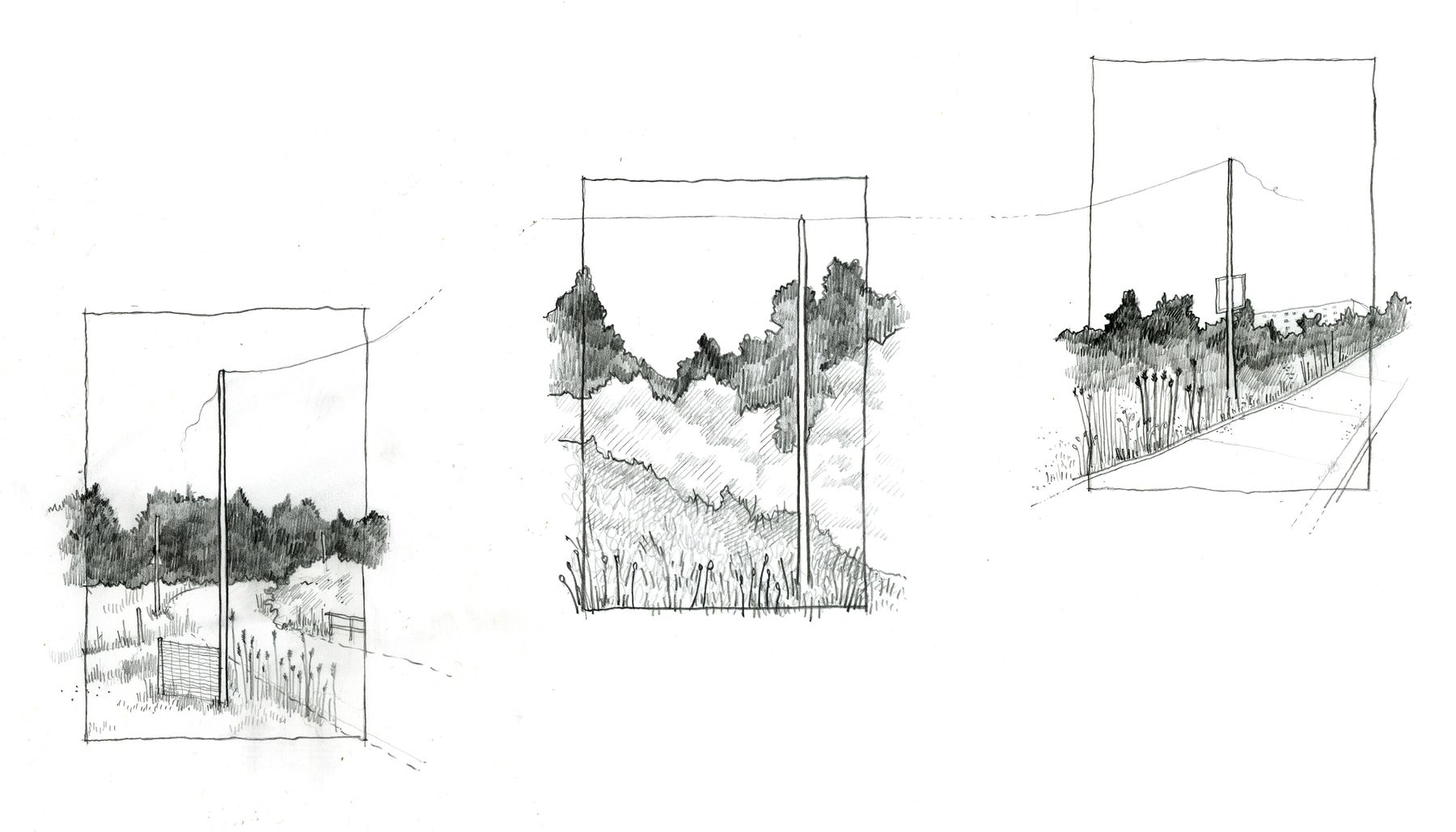

As an architect, my fascination with Eruvin began with the material making of these spaces. Although the Eruv is symbolic, it is also physical in its construction. The Eruv’s material re-establishment of an enclosure demands the reinterpretation of religious as well as civil law. Over time, an accepted protocol for creating and maintaining the Eruv boundary was developed, which further ordered a set of values for harmoniously integrating a place of belonging in an existing context:

1) Accessibility: The Eruv is made of everyday materials and artifacts that blend into the city and its infrastructure: fishing wire, 2 × 4 lumber, ribbon and string, tape, paint, lightweight steel signage posts. It is an accessible and cheap form of construction. It is non-invasive and practically invisible in the life of the city.

2) Partnership: The establishment of an Eruv requires a municipal authority to sign a lease. The community, Rabbinic authorities, or the Eruv committees “rent” the space required, creating a symbolically privatized domain. This lease does not prevent anyone from being in the designated territory but rather allows the community to borrow the space for their private use.

3) Negotiation: The establishment of an Eruv in a city space often requires the community to submit a building permit to the city’s planning committee. It cannot be built in good faith without approval from the board, city, or communities. It cannot exist within religious law without the approval and support of civic law.

4) Care & Maintenance: An Eruv is maintained and carefully managed weekly. It is invalid if it is broken or if the boundary has been obstructed in any way. Those who establish an Eruv are responsible for its care and their community.

In many ways, these form the conditions of the Eruv’s legal contract for its religious and civic existence: it relies on maintenance, it relies on active negotiations between the people and the city, and it relies on a form of collective belief and collective permission. Trust underlines the core of all these tenets.

I tried to find answers in Jerusalem. As soon as I started to pull on the figurative Eruv thread coursing through the city, an entire tapestry began to unravel. I found many examples of humble and well-maintained Eruvin around some neighbourhoods and privatized religious communities, but few were close to the city centre. They often encircled a gated neighbourhood and served a small community (such as Beit Me’ir) that maintained its boundaries independently, or wrapped themselves around small religious enclaves and newly-built neighborhoods.

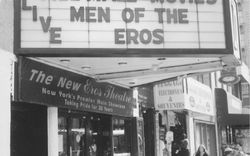

Within Jerusalem, a history of Eruv wars and untrustworthy bonds has led to a mess of non-functional Eruvin strewn throughout the city.1 I had the privilege of speaking to a handful of people involved in the Eruv wars, which occur between secular and ultra-Orthodox communities; each had strong opinions regarding the role of the Eruv. Secular communities claim that ultra-religious communities use Eruvin to take over established neighbourhoods for territorial expansion. Secular neighbourhoods like Kiryat Yovel aren’t concerned by the presence of different religious groups but believe the ultra-religious want to push out other residents to control the schools and public transportation, making the area uninviting. On the other hand, the ultra-Orthodox claim that the Eruv is their religious right and makes religious shared spaces more accessible and the city more devout, regardless of who lives there. Questions arise as to why a boundary would be desired in a small neighbourhood without a large ultra-orthodox community. Here, the Eruv transformed from a practice of leniency and acceptance into a practice of conflict, suspicion, and exclusion. The secular communities report, tear down, and vandalize the boundaries when they appear in their neighbourhoods without notice or permission, and the ultra-Orthodox communities repeatedly establish new, rogue Eruvin in the same areas, without necessarily intending for them to be completed or used. Activists on both sides used highly unusual techniques to reshape and change how the Eruv exists: making it more visible, layering multiple Eruvin together, hanging signage in protest, and demanding bus and train services change to respect the religious nature of the neighbourhood. In a place already so fraught over territorial practices, I was disheartened to see the Eruv deployed as a tool for division instead of symbolic inclusion.

As I drove from one neighbourhood to the next with my translator in tow and my camera slung over my shoulder, I was baffled to observe how the Eruv transformed into the most derivative form of architecture before my eyes. First, the Eruv formed a symbolic extension of the home woven through city walls. Then, the Eruv become a stealth form of urbanism across the Diaspora that reinterpreted everyday materials into architectonic forms. Then, as a tool used to claim space, the Eruv became a means of religious survival. The Eruv, which had always been synonymous with the notion of shelter and corresponded to the most basic formal conception of architecture as a space with walls, openings, and a roof for protection, now only evidenced a fraught history. It became an act of claiming territory, with its boundary signifying the control of space instead of the trust and diverse needs between pluralistic communities.

-

Yair Ettinger, “Rift Has Roots in Eruv Dispute,” Haaretz.com, February 22, 2010, https://www.haaretz.com/2010-02-22/ty-article/rift-has-roots-in-eruv-dispute/0000017f-f88b-d2d5-a9ff-f88f2acc0000; VINnews, “Jerusalem — Activists: Police Waging War against Secular Protesting Charedi Eruv,” VINnews, February 21, 2010, https://vinnews.com/2010/02/21/jerusalem-activists-police-waging-war-against-secular-protesting-charedi-eruv/. ↩

An Orthodox man walking under a kosher Eruv line in a small residential neighbourhood in Jerusalem, 2023. Photograph by Piper Bernbaum

The Eruv was written into the Talmud as a loophole to the Sabbath laws, recognizing that even though basic tasks could be completed in the home, many remain isolated from practicing and engaging with the Sabbath in the public domain of the city on the day of rest, especially women, children, elderly family members, or those with mobility issues or disabilities.1 By reinterpreting Talmudic law, the establishment of an Eruv reinterprets the territory of the city as well. Historically, cities had fortifications and walls that provided an “enclosed,” sanctified boundary. However, once Diaspora communities settled outside of Europe and the Middle East in places like North America, boundaries had to be created within alternative, existing infrastructures.

How does a placeless community establish a “home”? For thousands of years, Jewish communities have been making sacred space through legal fictions, establishing community by relying on symbolism and the reinterpretation of space, contract, law, and context when living in nomadic and diasporic conditions. The symbolism of the home is key in Jewish practice; many rituals and imagery evoke the concept of the home through metaphor and abstraction.2 Jewish communities build sukkahs for the holiday of Sukkot, which commemorates the forty years the freed Jewish slaves wandered the desert after their exodus from Egypt. The Mezuzah, a door marker that can be placed on the entryway frame of a house, sanctifies the home. Courtyards are considered spaces of mingling, viewed as a communal living room for multiple residential units, allowing for the sharing of space and meals. Even the synagogue is understood as a metaphorical household for the Jewish community. A Jewish way of life is a portable faith: you can take it with you anywhere you go.3

-

The Talmud, or Mishnah, is a code of laws perhaps best understood as a series of written amendments and debates on the ancient rituals and practices of the Jewish faith inscribed in the Torah. ↩

-

For further reading, see Mimi Levy Lipis, Symbolic Houses in Judaism: How Objects and Metaphors Construct Hybrid Places of Belonging. (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2011). ↩

-

Blu Greenberg, “Why Jews Hang a Mezuzah on the Doorpost,” My Jewish Learning, July 5, 2018, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/mezuzah/. ↩

In my many discussions with individuals involved in the Eruv wars, I asked about the leases signed with the city and the planning permits used to establish the Eruv within communities. This is common in North America and what makes it such a pluralistic practice. I asked: how was its contract formed? How were negotiations handled? In all cases, I received blank stares. These are not practices in Jerusalem—no lease, no permit, no negotiations. I was informed that, historically, one large Eruv in Jerusalem could be shared across many synagogues and communities, but now an unknown number of Eruvin manically overlap with this boundary, most of which are not documented or widely shared. Why? Because the communities do not trust one another to maintain the Eruv and to ensure the space remains kosher for use. Most Eruvin in Jerusalem seemingly exist out of self-concern instead of in the interest of collective care.

In Jerusalem, the Eruv still re-figures territory, but I believe these posts that I traced around the city and through the Eruv war regions are not Eruvin. At this point, the Eruv has become something else entirely. I believe that the values of the Eruv were always rooted in an act of participation, even in the early Talmudic interpretations. But without the ability or desire to negotiate its existence between people and place, the real and the symbolic, and context and commitment through contracts and agreements, the Eruv in Jerusalem is, perhaps, more fiction than legal fiction.