Soyinka’s Aesthetics and Monumentality

Emanuel Admassu and Zoé Samudzi in conversation

In February 2022, we agreed to read Wole Soyinka’s Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions (2019). We used his book as a frame to discuss continental African border logics, statecraft, and monumentality. This conversation, held on 16 March 2022, moves tangentially, building on some of the arguments presented in the book.

- ZS

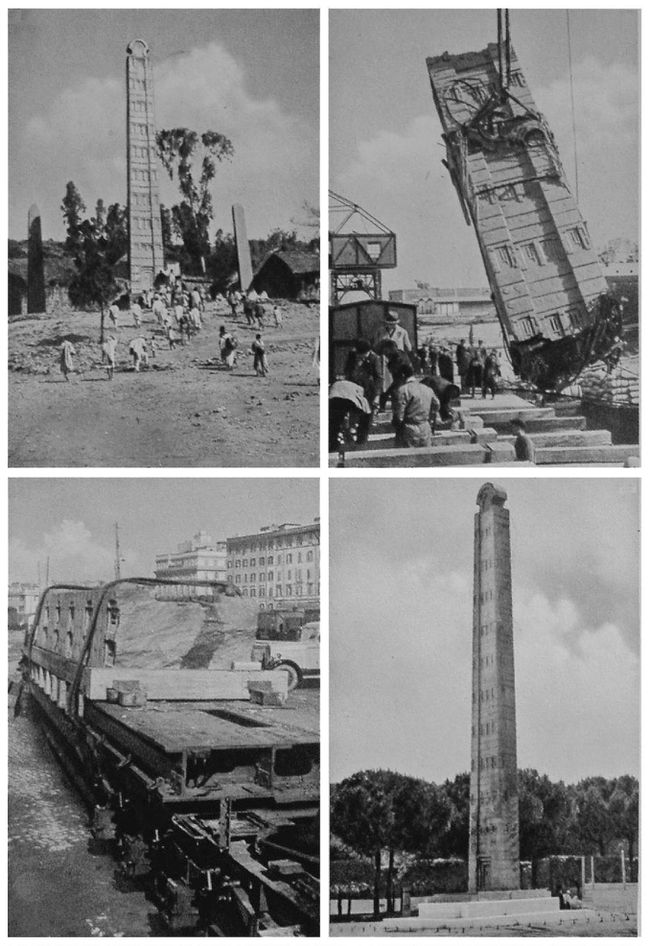

- I want to start with the anecdote from the preface where Soyinka describes Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade’s inauguration of the Renaissance Monument in Dakar. It was built between 2008–2010 by the Mansudae Overseas Project, the North Korean studio that also built the Tiglachin Memorial in Addis Ababa. Soyinka writes: “It is indeed a mammoth statue, the last word in monumentalism non plus ultra. Also remarkable is the fact that not one single aspect of its sculptural figuration bears the slightest resemblance to anything African, certainly not in concept, style, form, not even gesture. Aesthetic responses admittedly are mostly subjective, but even subjectivity involves a baggage of prior encounters or immersion in tradition that induces instant comparison.”1

He goes on to describe his encounter with Ousmane Sow whose sculptural work initiated the Renaissance Monument project. I wonder: what does it mean to reject an African tradition of monumentality? What political aspirations were African leaders gesturing toward in commissioning a North Korean studio? - EA

- There is another example later in the book where Soyinka writes about African spirituality in relation to Christianity or Islam. He speaks about it as a process of slow absorption or even domestication, distinct from tabula rasa.2 Recent Chinese and North Korean interventions offer versions of monumentality that are explicitly foreign to the African context. They gain their value by establishing clear differences, whereas the sensibilities Soyinka describes are about absorbing aspects of the surrounding landscape and translating them into a futuring project.

- ZS

- There seem to be two kinds of projects: the futuring project you’ve described, and a historicizing project. There’s no plane of the contemporary in this regime of memory.

In Namibia, there’s the Independence Museum, which is dedicated to the history of Namibia. And then there’s the Heroes’ Acre, which is based on the Revolutionary Martyrs’ Cemetery near Pyongyang. By a plinth at the very top of the Heroes’ Acre monument, there’s a statue of Sam Nujoma that doesn’t look like Sam Nujoma. As Soyinka says, no one “looks” African; these recognizable statues are also almost deliberately unfamiliar. - EA

- Those two categories are definitely familiar in Ethiopia. They’re both somewhat reactionary, and the historicizing project is always looking at particular monuments that are associated with the Ethiopian Empire: it looks at Axum or at Lalibela and finds ways to superimpose those expressions onto contemporary buildings. One of the most iconic examples is the Hilton Hotel in Addis Ababa, which has iconography drawn from Axum’s obelisk. Inversely, during the Derg regime, there was an effort to separate from that imperial history, but separating from that history meant associating oneself with the Soviet Union and a certain kind of pseudo-Marxist aesthetic.

For example, there’s a massive statue in the centre of Addis of Emperor Menelik II, whose legacy, especially as it relates to ongoing ethnic conflicts, is being revisited and scrutinized. There was no singular nation-state prior to Menelik II: he devised an imperial expansion of his territory and consolidated multiple kingdoms. The statue was erected during Haile Selassie’s regime, so it also symbolizes Haile Selassie’s attempt to claim a lineage and position himself in a continuous national narrative of resisting colonization.

Unlike the monument you described, it’s an accurate depiction of Menelik II on his horse after forging the nation-state—the emperor isn’t misrecognized. That is the privilege of not having had an extensive period of colonization: you can at least get the faces right.

- ZS

- You cannot misrecognize Menelik II, because without Menelik II, there is no Ethiopia.

- EA

- Yes, but it also seems to require the distance of time, because I don’t think they could have erected that statue while Menelik II was still alive. You either need the distance of time to be able to really canonize these figures or you need the distance of geography to lay claim to futures modeled by Beijing, Shanghai, or Pyongyang.

The description you gave makes me think about how a lot of African authoritarian leaders have associated themselves with North Korea or China as a way of negotiating domestic conflict. They begin to look at these references as models of suppression: to see the urban conditions that were produced and how they could be imported. That’s why North Korea was so important for Mengistu Haile Mariam, and why, for more recent Ethiopian leaders like Meles Zenawi, China was a model. - ZS

- That’s so apt, especially if we’re thinking about the post-colonial African state as the forcible consolidation of different peoples who probably wouldn’t share a singular identity otherwise. How do you hold it together? Often, by force.

- EA

- I think that also ties in with our conversation about permanence, because the territorial expansion of these kingdoms, at least the ones I’m most familiar with in Ethiopia, was temporary. There might be expansion into a certain zone for five years, but ten years later, it might be lost. The understanding of territory as something permanent that needs to be maintained through violence is inherited from elsewhere, and that’s the most powerful remnant of the colonial project: we’re fighting to maintain borders that didn’t exist before.

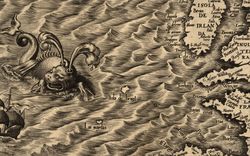

Recently, my research assistant found an amazing map that depicts small, ethnic territories. It’s an image of the African continent that is even more fragmented than the one we have grown accustomed to, but even that doesn’t do it justice because the borders are still drawn as solid lines. Drawing territories in the African context is deeply fraught. - ZS

- There’s no cartographic project that isn’t.

- EA

- It would need to be a non-static map…

- ZS

- Or maybe it’s a new kind of map. Soyinka writes about the myth of timelessness. He says: “Timeless, or ‘perennial,’ is perhaps what defines the world of antiquities, and it remains as much sought-after inner value in the craving of both artist and consumer. Its successful capture very much defines the realm of aesthetics, and this it shares with the essence of myth.”1 I think this really distills the purpose of borders and the myth of the state and its claims to permanence.

- EA

- The current prime minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, arrived on the scene as a populist uniting figure with hybrid identities: he’s kind of Muslim, he’s kind of Christian; he’s kind of Oromo, he’s kind of Amhara. Depending on the decision he makes, he gets rendered as one or the other.

His discourse around unity has made a lot of people think he’s trying to reclaim the aesthetics of the Ethiopian Empire and return to the politics of Haile Selassie. Then, in December 2021, he made a decision to release opposition leaders who were predominantly identified as Oromo. At that point, people said his project was an extension of Meles Zenawi’s project, which was about consolidating power around a single ethnic group: in Meles’ case, it was around the Tigray people whereas Abiy is allegedly engaged in a reparations project for the Oromo people. He’s allegedly enacting revenge politics against groups who had power. While commentators are trying to ethnically identify him, he’s exploiting that confusion in order to maintain power, which is why I have a feeling he’s going to be in power for a very long time. - ZS

- His ability to evade a typecast sounds contra to the way that, to deploy a favorite term of western political commentators, “big man” politics operate: that ham-fisted strong-arming into submission.

- EA

- But he also flirts with the “big man” aesthetic. When things were really unstable, he put on his fatigues and went out to the battlefield. He understands the power of the media without relying exclusively on censorship; he exploits fake news and all of these contemporary tendencies.

- ZS

- On Twitter, you can see how bot accounts seed and manufacture narratives that mirror the state because that digital infrastructure is about maintaining the state’s “peace.” So when people try to disagree with the politics, they’re being divisive or bloodthirsty or anti-Ethiopia or anti-Amhara. That seems more nefarious than outright censorship.

- EA

- And it relies on our addiction to real-time news through social media. I see how my relatives incessantly consume YouTube, which seems to have updates on the prime minister every hour. But none of it is verified information: it’s just some dude sitting in his living room and speculating, then everyone goes crazy on Twitter. People are interested in spicy interpretations and how those interpretations can be debated in the public sphere.

- ZS

- What you’re describing feels a lot like when Soyinka talks about the authentic or original fake: when he’s trying to purchase an item and no one can tell him where it’s from, but it’s real enough that no one can tell what they’re looking at.

I’m a fan of forgeries because it’s important to trouble monopolized notions of authenticity. There are three criteria for me: authenticity, legitimacy, and reality. Which is most important in evaluating a specific object or political claim that is being made by a statue? - EA

- What is the difference between legitimacy and authenticity? Is one about aura?

- ZS

- I think legitimacy is about aura. Even a reproduction, something that isn’t an authentic original, can still be a legitimate representation of however power was conceived in its original form. I think about that triad in the context of repatriation.

For example, the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island offered to make reproductions of their mo’ai (statues) for the British Museum in exchange for a sculpture called Hoa Hakananai’a held in London. The statues are sacred because they are physical representations of their ancestors, but the museum refused their offer. Why? No tourist who sees the statue in London will know the difference, but the museum knows it has power because the community is begging to have it back. They believe in the same regime of symbolic power as the people from whom they stole the objects. - EA

- I also think a lot of these museums do believe in the spiritual power of these objects. Meaning, I think there is fear. You might read it through karma or some watered-down western spirituality, but they are fearful that these objects have some sort of power that they can project onto their space or institution.

- ZS

- But they’re not fearful enough.

- EA

- Exactly. European and North American museums are fully committed to keeping originals as demonstrations of power even if that means they have to hire someone to come and “deactivate” those objects. And that’s bizarre. If you stole an artifact from my native land and you hire me to come to your museum and deactivate it, do you really think I’m going to deactivate it?

These museums believe that the power of these objects is nothing in comparison to the power they hold somehow. I think that’s why western institutions believe they have to be the stewards of cultural artifacts from all over the world: because they believe they’ll exist forever while other cultures will appear and disappear.

In his last chapter, Soyinka writes: “The objective of art is thus—among other purposes—revelation. This includes revelations of what is not! Whether revelation leads to social transformation or not is a different issue. The primary objective of art is also to constantly transform itself, its own modes of expression and representation. The compelling nature of art is the protean and chameleonic attributes.”2 This relationship between revelation and constant transformation could help us figure territory differently, especially in thinking about ongoing debates around the restitution of looted African artifacts. - ZS

- That’s complementary to when he talks about the ancient responsibility of the artist as revelation. The sculptor has already seen the non-apparent; the potter sees shapes in the formless mass, which offers an even greater semiotic power to these sculptures and monumentality as part of this bordering project.

- EA

- I really like that reading. Revelation is also about recognizing one’s own limits in attempting to understand these worlds or sensibilities. Every time Soyinka got to a point where he could articulate something in the book, he would question whether it was the full articulation of the idea, and then he’d double back. To me that’s revelation, because it requires an iterative practice of constantly challenging one’s ability to see, recognize, or acknowledge.

- ZS

- When Soyinka talks about museums as spaces of alienation, there’s that line: “Cultural negation becomes the handmaiden of racial disdain, and it’s not infrequent policy of eradication of the condemned humanity, piecemeal or in massed action.”3

- EA

- I couldn’t tell if he was explicitly addressing white supremacy; the way he uses “race” in that sentence is confusing. Right before that he was talking about absorption, so I wasn’t sure if he was saying white supremacy works through negation and these African spiritual practices operate through absorption.

- ZS

- There’s a benefit to that elision because he can maneuver in both directions. We can read him as making this almost anticolonial stand, but he can also be taken up by white western reformers. I was talking to a Nigerian friend about him and a certain generation of writers and thinkers, and he said that Soyinka writes like he’s asking the Queen for knighthood.

There’s a time and a place where that prose, ambiguity, and ambivalence makes sense—like when you’re a young intellectual and your newly independent country is missing art and you’re trying to cultivate a national cultural politic to articulate demands for its return. Authoritative declarations are coupled with uncertainty, but we can understand why since this is novel terrain. - EA

- Near the end when he was talking about art, there was this beautiful line where he was saying there’s a lot of regurgitation of ideology as a replacement for creativity.4

- ZS

- That tension between ideology and appraisal of creativity comes to the fore in the section about Black British artist Chris Ofili and his elephant dung paintings. Soyinka writes: “Was it really relevant that we knew what the medium was in order to form an opinion of its artistic value? Did the medium thereafter overwhelm the form, overwhelm the execution, overwhelm the tonalities, overwhelm the figurative composition itself?”5 That’s art’s million-dollar conflict: it’s a beautiful figurative work until you realize it’s made out of elephant shit, and then suddenly it’s heresy.

- EA

- It’s such a beautiful critique of globalization. And now we know the figure leading the campaign against Chris Ofili was Rudy Giuliani, who threatened to cut funding to the Brooklyn Museum after they included the piece in a 1999 exhibition.

- ZS

- And I do appreciate it in the context of tradition versus modernity. But when he defines modernity as “an expression of the condition of human society at any given moment, irrespective of culture and geography” I was a little confused. Immediately after that, though, he writes: “Modernity defines the immediate apprehension of time in its productive modes, and no one is about to argue.”6 That sounded right to me.

- EA

- Should we be attempting to recuperate modernity? Similar debates are happening about architecture’s legacy as a product of European imperialism: anticolonial arguments that reject boundaries of the discipline while remaining interested in and committed to spatial dynamics. I’m torn, because I don’t want to give up architecture. But as a political and aesthetic project, I understand the refusal to associate oneself with capital A-Architecture until we dismantle its colonial reflex.

- ZS

- What is coming out of architecture’s monument conversation? I’m wondering if the attempt to spatialize memory is not still a colonial practice of permanence. When you make permanent an idea in space, is this the genesis of a new way of relating to memory? Or, because you still have to ask the state for permission to commission this thing, is this not the state essentially capitulating and allowing a small concession and then kind of wiping its hands of further responsibility?

- EA

- Building particular monuments serves as an acknowledgement of history. But it simultaneously means (especially in the U.S.) that the state doesn’t have to actively address, for example, the material realities produced by slavery and its afterlives. That’s often what monuments do; they allow ambivalence and abstraction.

- ZS

- What does it mean when the context of visiting and interacting with these monuments is this kind of hybridization of education and entertainment? I’m thinking about different genocide memorials that exist like those in Rwanda and Cambodia—or, domestically, the former America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee or the National Lynching Memorial that went up in Montgomery in 2018—and what it means that these monuments to atrocity are tourist destinations.

- EA

- A lot of institutions are describing themselves as “living monuments,” suggesting that there’s the spatial artifact and then there’s programming around it that extends the conversation to the present. That’s one way to think about it, because you still need some sort of anchor or container that allows you to have these conversations.

- ZS

- I think it also begs the question: what is a non-living monument?

- EA

- Those are monuments that attempt to concretize linear conceptions of progress: we’ve confronted it, we’ve defeated it, and we’re better people because of it.

- ZS

- Where would we put the statue of Emperor Menelik II?

- EA

- The statue of Menelik II forces us to seriously consider his role in Ethiopian history—not only as an anticolonial figure who defeated the Italian army, but also as a figure that enacted an incredible amount of violence in order to expand his territory. Maybe that makes it a living monument.