Contested Territories of Prayer

Shukri Sultan on appropriating individual sacred territory in the city

How is sacred territory defined? In Western societies, the sacred is often marked in contrast to the secular with sharp distinction: it is confined between the walls of a place of worship or relegated to the private sphere of the home. Yet when we examine how Muslim minorities in Europe practice their faith, the very idea that sacred space can be distinct from non-sacred space is flawed. That is because salah, the ritual prayer that occurs at five prescribed times daily, renders the compartmentalization of religion impossible.1 Salah cannot be deferred to a later time and praying in a mosque is not always possible, especially given the rise of bans on minarets across the continent. So, like other Muslims, and particularly veiled Muslim women, in the United Kingdom, I redefine and renegotiate sacred territory daily when I appropriate banal space and make it sacred. This practice becomes an act of refusal—an act of reclaiming power—in the face of contestation around Muslim identity, especially that of the veiled woman.

-

In this text I use salah (also spelt salat) and prayer interchangeably, despite prayer being an incomplete definition. ↩

Dhuhr prayer during my lunch break in an unused meeting room of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Portland Place, London, September 2022. Photograph by author. © Shukri Sultan

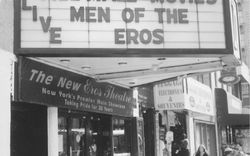

The establishment of official spaces for prayer—mosques—is also, along with Muslim identity, highly contested throughout Europe. Countries such as Slovakia have passed legislations designed to prevent Islam from being formally recognized as a religion, which makes it impossible to set up a mosque.1 Other countries such as France view mosques as a space of regulation and surveillance, inevitably leading to the production of a state-approved version of Islam. This hostile environment has forced Muslim communities to delineate sacred territory in creative ways. In Italy for example, where there are only eight mosques for the country’s 1.35 million Muslims, groups have established a series of spaces for worship in such unorthodox venues as supermarkets, apartments, garages, and discos. Documented by photographer Nicolò Degiorgis, who captures the contrast between the non-descript exterior of these buildings and the sacred space inside, these makeshift mosques transform the banal into the holy, expanding the definition of sacred territory to encompass the everyday.2 Hidden as they may be, they have not gone unnoticed and have been described as “clandestine and unregulated places” by Italy’s then Minister of the Interior Angelino Alfano. He even advocated for the closure of these furtive mosques to ensure that Islam is practiced in a place of “order”3—again signifying that registered mosques are a space for the state to exercise control. Other issues facing Muslim communities, such as the number of members outgrowing existing mosques or the difficulty of obtaining planning permission for new mosques, have resulted in worshippers pouring out onto the streets to partake in congregational prayers. This too has garnered extreme response—in 2010 French politician Marine Le Pen compared Muslims who pray in public to Nazi occupiers.4 Yet the practice of appropriating banal, everyday spaces for salah is not unique to twenty-first-century Europe; examples can be found throughout Islamic history. The Muslim community of seventh-century Arabia, who were then a minority in the city of Makkah, would use the home of Arqam ibn Abi’l-Arqam, a companion of the Prophet, to meet and worship in congregation. Similarly, the Muslim travellers who settled in Tang China in the sixth or seventh century likely used residential space for prayer as there is scant evidence of mosques built during this period.5 So when Muslims minorities today appropriate pubs, cinemas, or disused factories, they are continuing a long-standing tradition.6

-

“Slovakia Toughens Church Registration Rules to Bar Islam,” Reuters, 30 November 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-slovakia-religion-islam-idUSKBN13P20C. ↩

-

Nicolò Degiorgis, Hidden Islam: Islamic Makeshift Places of Worship in North East Italy, 2009–2013 (Bolzano, Italy: Rorhof, 2014). ↩

-

“Italy to Crack down on ‘Secret’ Mosques,” The Local Italy, 28 November 2015, https://www.thelocal.it/20151128/italy-to-shut-down-clandestine-mosques/. ↩

-

“I’m sorry, but for those who really like to talk about World War Two, if we’re talking about occupation, we could talk about that (street prayers), because that is clearly an occupation of the territory.” Marine Le Pen, quoted in Rose Troup Buchanan, “Marine Le Pen to Face Court for Comparing Muslim Prayers in the Street to Nazi Occupation,” The Independent, 23 September 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/marine-le-pen-to-face-court-for-comparing-muslim-prayers-in-the-street-to-nazi-occupation-10513920.html. ↩

-

Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt, China’s Early Mosques, 2018 ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015). ↩

-

The Old Kent Road Mosque, in South London, was originally a Victorian Pub and the Aziziye Mosque, in East London, was originally a cinema. ↩

Asr prayer in an awkward corner of Blackfriars Stations, London, August 2022. This is a location in which I have been reprimanded for praying. Photograph by author. © Jabir Mohamed and Shukri Sultan

These examples, both historic and contemporary, demonstrate that ritual prayer is a spatial practice and yet it is one that cannot be confined. Rather, as the Prophetic narrative states, the “entire earth has been made a place of prayer.”1 Salah is an exercise that connects us Muslims not only with God but also—given the prescribed times of prayer dictated by the earth’s orbit of the sun—to the wider cosmos. Historically, prayer time was calculated either using an astrolabe or by measuring the shortening and lengthening of one’s own shadow. The outward actions of the prayer—standing, bowing, prostrating—link the body to the inner, intangible dimensions of prayer (the cultivation of presence), forging a connection between body, soul, and cosmos.2 Salah is a unifying practice that is intended to make us receptive to natural phenomena around us. With the mechanization of time, the daily prayer serves as a reminder that time is subjective and divine.

The rhythm of salah also affects how we interact with the city. Just as the prayer schedule is determined by the orbit of earth, our lives in turn orbit the prayer by scheduling everything around it. The goal of the ritual prayer is to fully detach oneself from one’s surroundings and enter into an intimate dialogue with God. It is an exercise in mental discipline—in the age of constant notifications and distractions the task of switching off for five minutes and cultivating presence requires more self-control than one may anticipate. To reach this meditative state, a quiet space is needed. Reflecting on my own experience, the search for a prayer space starts before I even leave my home. When cycling, I plan my route to allow myself the option to stop and pray in a park. In other instances, when time is of the essence, I have learnt to improvise, seeking out stairwells, quiet corridors, storage cupboards, and changing rooms to appropriate. My choice of location is determined not only by quietness but availability, proximity, privacy, and most importantly safety, as prayer is not only a spatial practice but an embodied one that is impacted by societal limitations placed upon the body.

-

As Hadith says, “The entire earth has been made a place of prayer, except for graveyards and washrooms.” Abu Amina Elias, “Hadith on Prayer,” Daily Hadith Online, 23 March 2013, https://abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2013/03/23/whole-earth-is-a-masjid-mosque/. ↩

-

The traditional methods of measuring prayer time, through the use of an astrolabe, sundial, or the body, have now been replaced by mobile applications. ↩

A very late Maghrib prayer on a side street in Hammersmith, London, August 2022. Time here was of the essence, hence the grubby setting—I was having dinner nearby and remembered the prayer with only 5 minutes remaining of the prescribed time. Photograph by author. © Shukri Sultan

The very notions of citizenship and the right to existence are particularly intertwined with the highly politicized body of the veiled Muslim woman. Legislations designed to police it—in the form of bans on the niqab and hijab proposed under the guise of national security, “anti-separatism,” or the age-old colonial nonsense of liberation—have resulted in the marginalization of Muslim women in the public realm. This veiled body is a battleground for opposing ideologies, each wishing to exert control over and appropriate it for political advantage. It is a body that in the eyes of many does not exist in its own right—it is devoid of autonomy, only ever seen in relation to a male authority figure. When we are described as “traditionally submissive” or compared to “letter boxes” and “bank robbers”—the respective words of former British Prime Ministers David Cameron and Boris Johnson1—even walking, cycling, or skateboarding—simply existing and taking up space—is transformed into an act of resistance.

As Martiniquais political philosopher Franz Fanon wrote in the 1960s, the “woman who sees without being seen frustrates the colonizer.”2 In recent years, this frustration is increasingly being exercised through acts of violence in public spaces. Whether it be in a cafe in Sydney;3 underneath the Eiffel Tower;4 sitting on a bench in Montpellier;5 or while waiting for a train at a London Underground station;6 women who appear to be visibly Muslim are being violently attacked. In fact, British spoken word poet Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan argues that “our hijabs are pulled off in the street because they are criminalised at state-level”7—in the week following Boris Johnson’s callous remarks, there was 375 percent increase in Islamophobic attacks.8 Feminist geographers have researched and written about the effect that fear plays in how women navigate public space.9 But for Muslim women this common fear is exacerbated with the looming threat of such racialized, gendered violence. So, when I roll out my mat for the maghrib (dusk) prayer on a side street in central London, my intention is to submit myself to my Lord, but my devotional act unintentionally becomes a defiant one.

-

Matt Payton, “Muslim women ridiculing David Cameron over comments about ‘traditional submissiveness’,” The Independent, 25 January 2016, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/lim-women-ridiculing-david-cameron-over-comments-about-traditional-submissiveness-a6832351.html; Press Association, “Boris Johnson cleared over burqa comments,” The Guardian, 20 December 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/dec/20/boris-johnson-cleared-over-burqa-comments. ↩

-

Franz Fanon, “Algeria Unveiled,” in A Dying Colonialism (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 44. ↩

-

“Pregnant Muslim woman attacked in Sydney cafe feared she would be killed, court hears,” The Guardian, 15 September 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/sep/15/pregnant-muslim-woman-attacked-in-sydney-cafe-feared-she-would-be-killed-court-hears. ↩

-

“Two French women charged over ‘racist’ stabbing of veiled Muslim women,” France 24, 22 October 2020, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20201022-two-french-women-charged-over-racist-stabbing-of-veiled-muslim-women. ↩

-

@DecolonialNews, “Aujourd’hui à Montpellier, plusieurs jeunes femmes musulmanes dont certaines portant le #Hijab se sont faites agresser par un homme,” Twitter, 12 April 2022, 10:09am, https://twitter.com/DecolonialNews/status/1513882082912710676; Anadolu Agency, “Man to stand trial for assault of 2 Muslim women wearing hijab,” Daily Sabah, 16 April 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/world/islamophobia/man-to-stand-trial-for-assault-of-2-muslim-women-wearing-hijab. ↩

-

Caroline Mortimer, “CCTV footage shows moment pensioner ‘deliberately’ shoved woman into path of London Tube train,” The Independent, 19 April 2016, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/cctv-footage-shows-moment-pensioner-deliberately-shoved-woman-into-path-of-tube-train-a6991566.html. ↩

-

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, Tangled in Terror: Uprooting Islamophobia (Northampton: Pluto Press, 2022), 169. ↩

-

Nawal Mustafa, Muslim Women Don’t Need Saving: Gendered Islamophobia in Europe (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, 2020), 6, https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/gendered_islamophobia_online.pdf. ↩

-

Leslie Kern, Feminist City: A Field Guide (Croydon: Verso, 2020). ↩

Isha prayer, Bartlett Library, University College London, December 2021. Photograph by author. © Shukri Sultan

Prayer, a practice so ordinary but integral to my spiritual and mental wellbeing, is also fundamental to how I participate in and exercise my right to the city, particularly in the face of the increased privatization, regulation, and monetization of public space. When my ability to pray in public is limited, so is my access to the public realm.1 For example, despite taking measures to appear inconspicuous, I have occasionally found myself being politely reproached for praying in a corner of a train station, as the act is still regarded as a violation of the codes of conduct governing that space. Through prayer I bring to the foreground the hidden rules of neoliberal urbanism that may not have been perceptible. By delineating urban sacred territory at the individual scale, Muslims become part of the wider conversation around who has the right to access, occupy, and be visible in the city.

Redefining and renegotiating sacred territory are necessary for salah—the defining practice of a Muslim life—to be sustained. Finding space for prayer is a requirement for cultivating and nurturing a healthy spiritual life, which in turn alleviates and softens the difficulties that accompany life in the modern metropolis. Yet, in a highly polarized Europe, this vital act of worship will always be perceived as a strange act performed by the other. For this to cease to be the case, Europe has to not only reassess its relationship with Muslim minorities but also confront the narrow parameters of its own identity that require othering.2 Until this happens, the Muslim sacred territory, whether officially demarcated by the walls of a mosque or temporarily marked out by my mat, will always be a contested and politicized space. And a Muslim women’s body will continue to be used as a “playground for racist misogyny,” limiting her access to the public realm.3 And yet, every time I unroll and lay out my prayer mat, I carry on exercising my right to my space in the city.

-

The limits on space for prayer have been recognized by corporations wishing to reach Muslim customers and visitors. So now one can find designated quiet spaces designed for prayer in recently built shopping centres. Similarly, institutions endeavouring to create an inclusive work or educational environment have allocated quiet and prayer spaces. ↩

-

Who Europe considers to be worthy of citizenship has been brought to forefront with the Ukrainian refugee crisis. Politicians and journalists have openly stated that sympathy and citizenship should be extended to those who are “civilized” and “look like us.” Moustafa Bayoumi, “They are ‘civilised’ and ‘look like us’: the racist coverage of Ukraine,” The Guardian, 2 March 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/mar/02/civilised-european-look-like-us-racist-coverage-ukraine. ↩

-

Lola Olufemi, Feminism, Interrupted: Disrupting Power Book (London: Pluto Press, 2020), 87. ↩